I’ve had eleven days since To Pimp a Butterfly came into my life like a marauder past midnight and kept me up until the dawn. Some songs have become soundtracks to long runs around the river in the cold grip of spring mornings, some to sleeping bus rides on the way home, some to pre-meeting personal hype sessions in my office. In that time, the entirety of the work has seeped and soaked into my life and colored it with Kendrick Lamar’s voice and Thundercat’s rolling bass licks and Flying Lotus’s strange and spacey synths. The hairs on the back of my neck stuck up after my first full listen because I knew I was listening to an event, as much as to an album. This was a magnum opus.

Listening is a tricky and slippery thing, though. Moods and attention spans at the moment bring out certain things and dull others. And the layers that press against the edges of my awareness now aren’t the same layers that grabbed me at first. Even over eleven days, plenty of the album is half-digested and waiting for another listen. I suspect things will be the same after 100.

The first night and few days after, the elements that caught me were the lushness of the arrangements and the pure instrumentation of Kendrick’s voice. The first suite of the album, from “Wesley’s Theory” to “Institutionalized” is a hybrid of P-Funk and Sun-Ra’s jazz, electrified by Thundercat’s rambling, fat bass and Kendrick using multiple voices to imitate P-Funk’s classics: George Clinton’s space radio jockey as the ominous narrator on “Wesley’s Theory” and a Bootsy-through-Andre 3000 helium high-pitched alien voice on “Institutionalized.” This album finds Kendrick maximizing the capabilities of his own weird voice in both senses, but the physical elements – the screeching, the angry brute-force machine gun, the low rumbles, the off-kilter crack hiss and the drunken lurch – add to his greatest strength: his ability to inhabit the bones of any character and make them distinguishable. Not to be hyperbolic, but the last rapper that I’ve heard with this kind of vocal chameleon ability was gunned down in LA in ‘97.

This was a magnum opus.

There’s so much more just to the damn sound of the thing, which I think alone would make it worth a listen. Flying Lotus is only listed once, but his recent sound colors the entire effort. “King Kunta” properly gives James Brown his due as a direct father of rap. “These Walls” matches Bilal’s, Anna Wise’s, and Kendrick’s eerily similar voices with a Terrace Martin sax and a fucking mean Robert Glasper solo. “u” features some of the best brooding bass work you’ll hear this side of a Blue Note album and crazy spazzing sax solo. “Alright” is classic Pharrell chill-hop, but done with the Glasper and Martin-led house band, which takes what is essentially the backbone of Rick Ross’s “Presidential” to entirely new heights. “For Sale?” is a hybrid of jazz and synth-psych, and somehow makes a Willy Wonka ripoff one of the best instrumentals of the year. “Hood Politics” and “How Much a Dollar Cost” manage to drench Dr. Dre’s G-Funk drums and fat bass lines with eerie, somber post-R&B soundscapes. “Complexion” and “You Ain’t Gotta Lie” are neo-Tribe, and “The Blacker the Berry” is a direct descendant of Kanye’s rap-metal from “Yeezus.” The sounds themselves tell a multi-layered story of struggle and hope and fear.

But then there’s the words themselves; the verbal portions of the stories Kendrick told throughout the album. The opening suite from the needle dropping from the “Every Nigger is a Star” sample on “Wesley’s Theory” to “Institutionalized” tells a story of a successful rapper who made it, struggles with consumerism and decision-making, and is haunted by tax collectors and American greed. “For Free,” “Institutionalized,” and “King Kunta” do an excellent job in this stretch of making the same kinds of parallels between slavery and consumer culture, and “For Free” makes a point of inverting the Mandingo myth in the service of a story showing Kendrick’s “freedom” via purchasing power. King Kunta’s rebellion is incomplete and hollow, with echoes of Watch the Throne’s story of defiance via opulence. But through the paranoia about Uncle Sam throughout and the inability to leave crime behind in “Institutionalized,” it’s clear that Kendrick views this version of success as ephemeral.

The second suite is what sticks to me the most. “These Walls” is a standard jazzy double entendre about sex until the third verse, where it becomes a triple entendre (word to Hov) about how Kendrick’s main character is sleeping with the former flame of the man who killed his brother in the first album. It becomes clear that this is an EVIL song, a true manifestation of Kendrick’s spreading id and the demons that haunt him. It’s fitting that the next track, “u” is a self-loathing, drunken mess. Kendrick wrote that this song was the hardest for him to record, and it shows. As a person who has battled the same emotional and substance issues as described here, I can understand why. The song is raw, it’s real, and it reminds me of my own low points. Just the feeling of being reminded by the period in my own life or writing these few sentences about it is like scraping a razor over my soul, so I simply can’t imagine what it felt like writing and performing.

In this context, the following song “Alright,” feels like a false euphoria. A post-depression high common to many that glosses over the emotions without addressing them. It’s fitting that “Lucy” first reveals his ugly, horned head in the lyrics. The next song, the stellar “For Sale?” is where Lucy, the devil, gets his shine, offering to buy the rapper’s soul. Here we see an inversion of “For Free” and a clear rejection of the Watch the Throne prescription of decadence as therapy (if it isn’t clear here, I think this album is in very, very close communion with Kanye and Jay’s effort, as is much of current hip-hop). I’m not sure if I’m reaching on artistic intent here, but there also seems to be a theme of Kendrick’s ongoing distrust of “Illuminati” imagery and references in rap (again, a rejection of Watch the Throne). Kendrick’s story of a rapper buying his freedom is first marked with jubilation, until he soon finds another tax collector hot on his heels, this time the kind with a pitchfork. Here, the Willy Wonka soundscape suddenly makes sense. What was Wonka, other than a saccharine devil luring kid Fausts with candy?

The next suite of To Pimp a Butterfly, from “Momma” to the end, feels like Kendrick completing one journey and beginning another. “Momma” is a song about Kendrick’s visit to South Africa and his partial enlightenment there, a theme repeated through the message of self-love in the following songs. The lessons he seems to have picked up there seem similar to my own, and indeed similar to many young Black leaders who went “home” to Africa and found threads of kinship and humanity reflected back in the pools of faces like their own. “Hood Politics” is the beginning of Kendrick’s attempts at spreading a coherent message (a striking one–how can we proclaim gangs as termites chewing away our country’s moral fiber when “Democrips” and “Rebloodlicans” are doing much worse at higher levels?), but “How Much a Dollar Cost” is the musical and lyrical centerpiece of the album and probably of Kendrick’s work up to this point. Turns out the pieces like this were supremely prescient, as they indicated Kendrick’s turn to deeper religiousness in songs like this. “How Much…” is simply beautiful, a song about Kendrick’s hardened and greedy character being challenged by poverty and the promise of Heaven from a Jesus figure. The song shows the full extent of the role of faith in Kendrick’s life, and it clearly isn’t a small one. I feel that the end of the song represents him being saved, a full 180 from the days of keeping an ear to his demons, although an acknowledgement that they will always run with him. The following songs from “Complexion” (featuring a killer verse from Rapsody–notably the only full rap feature verse on the album) to “Blacker the Berry” and “i” are Kendrick trying out his own voice as a Black leader with newfound conviction for the first time.

Then there’s “Mortal Man,” which I’ve been listening to for an hour straight as I write this essay. There are songs that fade away soon, there are songs that are seasons in life and there are songs that become part of the tapestry of life. For me, “Mortal Man” might be part of my tapestry. I haven’t heard a song that hit me so immediately as a developing person since maybe “Aquemini” by Outkast. As a young Black man struggling with developing my Blackness and manhood in a world where my very existence is seen as a lethal weapon, and as a person still grappling with violence that has recurred in my own life, with casualties among my own friends, “Mortal Man” is kind of a distillation of my experience. I can feel that Kendrick yearns to be a leader of men and to help communities that he loves more than the skin on his own back to prosper. I can also feel him grapple with the same questions about revolutionary leadership in relation to Mandela, MLK, Malcolm and others and the burdens that come along with that mantle. I struggle with them daily too.

“Mortal Man” places the rest of the album in a timeless context. Kendrick has grown from a good kid in a mad city to a weary aspiring leader in an insane world, with the crown for which he fought so hard becoming an unimaginable weight on his head. That origin story mirrors so many others in Black History. As much as To Pimp a Butterfly is an obvious letter to Kendrick’s idol Tupac, it’s also a poignant homage to Nelson Mandela and other Black leaders. I’ve been to Robben Island, and the chill of the spirits there settled into my bones like a cold I’d spent my whole life trying to catch. It has never left, and with Mandela’s passing from the world, I believe the fever has only been stronger. I imagine the experience had a similar effect on Kendrick Lamar. In acknowledging his own mortality and detailing the questions he struggles with, he also opens up the possibility that he could be wrong; that he is still developing his identity as a leader.

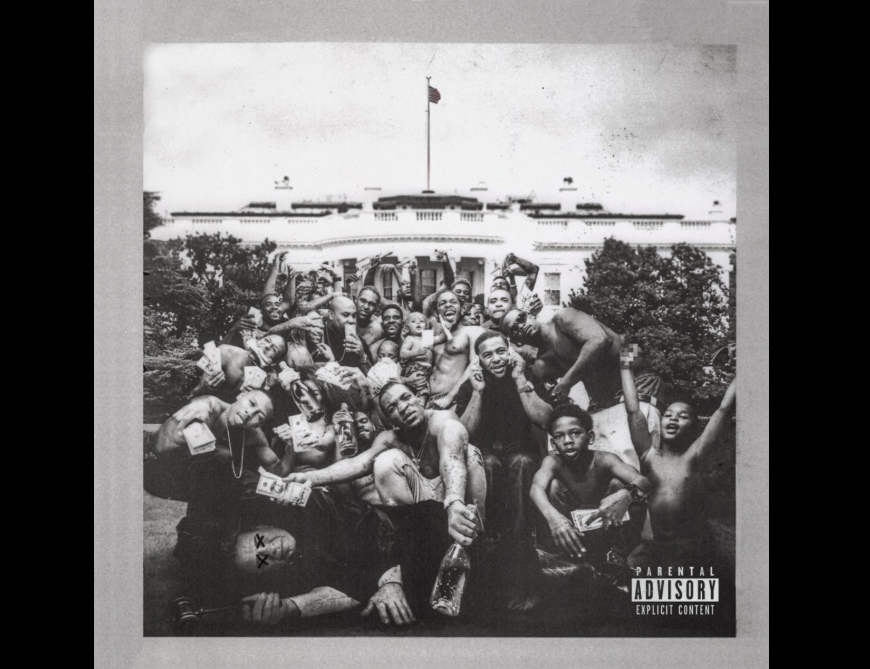

It’s this honesty and his true agnosticism of ideals that make some things like the cover and certain messages in “Blacker the Berry” seem like tolerable missteps or thought experiments of a man trying his damnedest to just work things out to be a better person, rather than misguided marks of self-hate. Even the cheesiness of “i” sounds much better in this context (albeit with a much crisper live-style arrangement than the single version). It’s clear that the message of self-love has meant a great deal to Kendrick, and while the beginnings of his movement philosophy take that message to the doorsteps of places that I cannot go, To Pimp a Butterfly is a great way to understand how he arrived there. The album encourages nothing if not empathy.

I wrote earlier about the portents of this album becoming the bedrock of a new wave of Black protest music. I think that somehow, I managed to undersell it. To Pimp a Butterfly is unapologetically and adamantly Black, in a way that makes its very existence a protest. But the messages are a bit deeper than that. This album is about personhood, about manhood and Blackness and honesty and hope and despair. Each of these facets is its own protest.

This is an epic poem, dedicated to understanding the very core of Blackness and self. I’m not sure about what others may rate it out of how many stars; truthfully I’ve waited to read anything about it until I finished this. But I consider To Pimp a Butterfly a masterpiece; a mirror to pieces of my own soul, and an inspiration. And I think that if more artists take the time to try and craft pieces of art like this, they could be as impactful as any speech or slogan. Every bit helps.

we might be alright.

Comments

Indeeed! A great poem! In my personal time I’ve realized that this album takes the listener on a journey. A long, meaningful journey.