April 5th, 1915

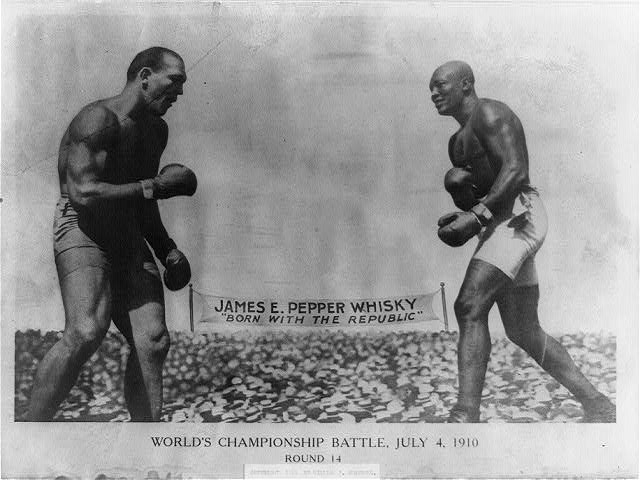

The spectators still keep pouring in. The racetrack in sweltering Havana. White Americans and Europeans stream alongside Cuban men in in suits and panama hats as President Menocal looks on. Jack Johnson and Jess Willard, two giants in silk robes, step into the ring pouring sweat. Willard weighs in first, a great big oak tree of a man. He towers over Johnson, but the Negro fighter is still in prime fighting condition. Johnson goes over to the ropes to wave to his wife, a white woman of all! The fighters go back to their corners and the bell rings. The fight is on.

The war had not yet started then. Not for the United States, and not for its ally Cuba, which had still not fully emerged from its status as a Yankee protectorate after the Spanish-American war. So people back in the States waited to read news of the fight with as much anticipation as they would have for daring accounts of Roland Garros shooting down German planes with the Escadrille.((Sources for this post: Ken Burns PBS documentary “Unforgivable Blackness” and the April 6th, 1915 Edition of the Fairmont Times-by Damon Runyan))

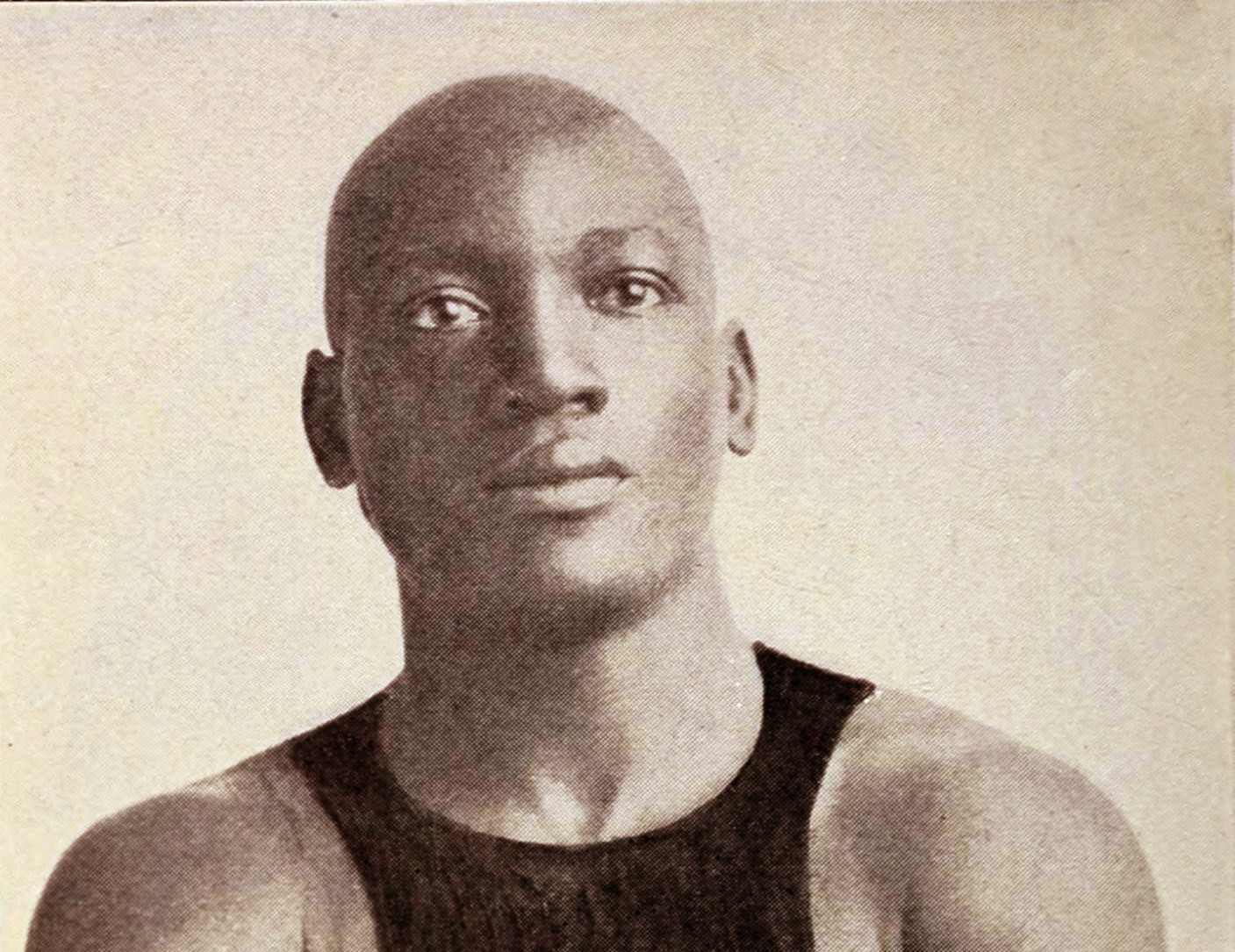

There was Jack Johnson. The Galveston Giant. The aging pot-bellied Negro heavyweight of all heavyweights; the man who for almost a decade had delivered Herculean body blows to the Jim Crow South as boxing’s heavyweight champion. Lumbering from the opposing corner was Jess Willard, a six foot-six cowboy from Kansas. The slow, but powerful and indefatigable “Great White Hope” with sledgehammer fists and an iron jaw. Across the country, Black Americans waited with bated breath as the man who had broken the heavyweight color line and defended challenge after challenge fought against hope while much of White America waited with glee as the latest hand-picked and groomed challenger finally stood poised to knock that man down.

It hadn’t always been this way. Johnson had been an unknown fighter at the turn of the century, an anonymous son of a Union Negro soldier toiling in street brawls between New York and Texas. He was on the absolute periphery of the Negro prizefighting universe, and envisioning him one day crossing the color line for a title was unthinkable. But a jail stint and a run-in with aging Jewish legend Joe Choynski, a man who became his mentor and friend, helped Johnson develop a reserved and defensive style which combined with his formidable strength and stamina to create one of the first truly modern Black fighters. The three years following the 1901 jail term and his style reinvention were a whirlwind of success for Johnson, and by 1903 the “Galveston Giant” had claimed the undisputed Colored Heavyweight title. He would go on to hold that title for five straight years.

Tenth Round: Willard forced the fighting and landed left to face. Johnson drove Willard to the ropes with a volley of blows to the face. The negro landed his right on Willard’s body, followed with a terrible right to Willard’s jaw. He was trying for a knockout. Johnson’s round.

Johnson’s next true opponent was not a man, but the color line, the Jim Crow distinction between the Colored Heavyweight and the general World Heavyweight titles. James Jeffries, the heavyweight champion from 1899 to 1905, refused to fight Johnson, and Johnson had to follow his predecessor Tommy Burns to fights around the world and taunt him for years before he accepted the bout. Burns would eventually accept. Burns would eventually lose. And in 1908, Jack Johnson would become the very first Black World Heavyweight Champion in history.

During Johnson’s long reign as champion, he developed the persona of perhaps the first true modern pop athlete. He was an endorsement machine, proving his marketability even in the most racist parts of the Deep South. His pride and boastfulness ventured well into the territory of arrogance and pompousness, and he flaunted a voracious appetite for women (especially White women), sex, fast cars, and partying. This strain of belligerent Black antiheroism in the face of deep racism would be the template for many Black trash-talking warrior-pugilists, from Ali to Tyson to Mayweather, and his in-ring style would also be mirrored especially by Tyson and Mayweather. Ken Burns’s documentary on Johnson, aptly titled Unforgivable Blackness, details the boxer’s incorrigible spirit and constant clashes with whiteness.

Johnson’s cultivated image was the forebear of the development of a certain dominant strain of Black athletic image to this day. There was a lot of Jack in Ali and a lot of Jack and Ali in Tyson. There was a lot of Ali in MJ and Shaq and Deion and Ray Lewis. And there’s a lot of Tyson disseminated throughout current professional leagues. Given boxing’s status as America’s first true organized sport, it may be fair to say that Jack Johnson is one of the archetypes-the Platonic ideals-of Blackness in sport.

Twentieth Round: Johnson jumped from his corner and landed his left to Willard’s face and then landed five swings. Willard clinched and landed his right in the body. Jack drove Willard across the ring, landing several blows on the head. Willard landed right and left to the body. Johnson’s round.

Even after Johnson grabbed the title, somehow the powers that be still maintained the color line in the heavyweight class. Johnson never faced a Black fighter in a title bout, and in fact the next Black heavyweight champion would come three entire decades later, when Joe Louis won in 1937. Many blame the long wait and the pressures on Louis’s own career on supremacist backlash to Johnson’s brashness and fondness of White women. Johnson would face strings of Great White Hopes, promising boxers or former champions selected and often paid handsomely to defeat Johnson.

The most serious of these challengers was James Jeffries, the man who had retired rather than defend his title against Johnson. He came out of retirement as a farmer for a $120,000 draw to fight Johnson and had to lose over 100 pounds. This “Fight of the Century” was set in an arena and a time that was fraught with the threat of racial violence, and the venue itself restricted guns and alcohol. Johnson thoroughly dismantled Jeffries in a relatively anticlimactic fight, as Jeffries’s side threw in the towel halfway through the bout to save face and avoid a knockout.

Twenty-Third Round: Willard jabbed Jack’s face with left. They clinched. Johnson intentionally let Willard hit him in the stomach six times in clinches then laughed. Willard swung and missed with his right. The round was even. It was more of a horseplay than a prize fight in this round. Willard jabbed Jack’s face with left. They clinched. Willard’s round.

The true climax of the Fight of the Century would not be had in that ring. Across the country, receipt of the news of the outcome of the fight set off race riots, usually instances where Whites attacked Black institutions or where Black celebrators were brutally beaten and broken up. Several people were killed, all of them Negroes. Ali’s fights half a century later were set during dangerous times as well, and there was a danger in his character that went beyond simple daring. However, no sportsman in American history was deemed as dangerous in success as Jack Johnson. The riots showed that danger. The riots showed that fear. Film of the fight was banned in many states, and Congress so feared further riots that the cross-state distribution of all fight films was made illegal for 30 years.

Johnson endured as champion, even though the color line was still maintained, in part by Johnson. The biggest draws to be had were in defeating White challengers. However, in a farce, his title was declared vacated in 1913, a move that set the table for him to fight challenger “Battling Jim Johnson,” a Negro fighter with more losses than wins. Johnson toyed with him with one arm until the fight was declared a draw, an outcome that led to Johnson regaining his title. Another string of lesser opponents, again all White, would ensue.

Still, Johnson held on to his title through the turbulent years after the fight. After his first wife, Etta Duryea, committed suicide, Johnson married his second wife, Lucille Cameron, and was promptly threatened with lynching by several white leaders in the South. Both women were White. Supremacists used rumors that Cameron was a prostitute and other rumors of Johnson associating with prostitutes to convict him under the Mann Act, a legislation that had not even existed when the alleged acts were committed. Instead of surrendering, Johnson chose to leave the country. Cuba would be his closest to returning to the U.S. until he turned himself in to authorities in 1920.

But all prospectors strike gold with enough time. Jess Willard, the next Great White Hope, would turn out to be that gold for white supremacists. A powerful brute of a man who easily outclassed Johnson’s imposing stature and who may have been the heaviest and tallest man to contend for the heavyweight title to that point, Willard had killed a man with a single punch in the ring in 1913. He was chosen to face Johnson with a singular purpose: to knock him out.

Summary: Crafty warfare of ageing Negro in opening frame of Havana Championship. Bout much admired but not sufficient to stem the tide of youth and to hold out to win from Kansan–badly hurt by blow to stomach in 26th. Champion offered no defense as huge right fist sent him to dreamland.

And then it was over. Johnson flagged in the late rounds of the scheduled 45-round fight, and by the 23rd he was visibly exhausted. Willard was indomitable, a spirit of plodding determination and a seemingly infinite capacity for punishment. When Jack Johnson hit the mat, he would stay down, as would his career. Jess Willard, the Great White Hope fulfilled, would be celebrated across the nation as a hero. Said Jack Curley, an influential boxing and wrestling promoter of the time:

I knew Willard would win. He is the greatest heavyweight of all times. No man on the pugilistic horizon has a chance with him. Willard as yet has not reached the crest of his ability. Willard will take a brief rest and then will meet any white fighter. He will probably draw the color line. The fight was a big success. Willard deserves the thanks of the entire white race for its glorious victory-bringing back to the white race the heavy-weight championship title.

Johnson lived a long (and colorful) life post-boxing, including decades of fights at the fringes of prizefighting’s core. But he would never again challenge for a title, not even the colored championship. He returned to the States and served his prison time, even somehow earning a patent in the process. He fought until his end at age 68, for decades as a pitiful old fighter in sideshow events.His death would come in one of the moments of excess that he loved, speeding, after being refused service at a restaurant in Raleigh, NC in 1946. Even Johnson’s very death was an act of defiance.

Only a single marker for “Johnson” now notes the place where Jack Johnson’s body was laid to rest. But his legacy has permeated American sport, American history, and Black History. Every hook Ali dodged, every uppercut Tyson landed–even every shoulder roll Mayweather executes with polished perfection–they all have a bit of Johnson’s DNA programming them. Johnson was a flawed man. He wasn’t a perfect activist, and he may not have considered himself a fighter for anything other than himself. But he was a quantum leap; a man who was literally ahead of his time and who through sheer force of will was able to live a life of unapologetic and unadulterated Blackness. A century later, and we could stand to learn much from him.