The flood started with a flood. Sure, there was a certain wayward trickle of Blackness that found itself absorbed into Ellison’s cans of paint in places like St. Louis and Chicago and Milwaukee before, but things really got to moving when the levees broke for the first time. On a summer’s day in ‘26, eighty years before Katrina, the rain started in Kansas along the central basins of the mighty Mississippi and wouldn’t stop. For over half a year, a constant barrage of precipitation had swollen the aorta of America to more than twice its size. By Christmas, parts of the river reached record heights of near 60 feet, almost six stories. There was simply no way to avoid the coming catastrophe.

Over the course of the following spring, the unstoppable wall of water, rushing due south with more volume than the Niagara Falls and at times more force than a speeding locomotive, destroyed hundreds of levees from Kansas to Louisiana and brought devastation around the river. Down a 100 mile stretch of river there were floods up to 30 feet deep, 25 miles out on both sides. The damages were staggering, costing the area an estimated 5.4 billion dollars when adjusted for inflation. The places hardest-hit were the nascent Black communities along the rivers. The tent towns and shacks and reclaimed outskirts of plantations where Black craftsmen and laborers toiled to shape lives from the unforgiving hard clay of White supremacy.

When the flood waters finally receded, most of the 600,000-plus refugees that were forced out of their homes were Black, and instead of accepting relocation under increasingly hostile and racist local officials, many of them used this forced untethering to move to the industrial cities to the north of the floodlands. Those movements became the backbone for the larger Great Migration, perhaps the single-greatest demographic shift in this country’s history.

Historical disasters like the Great Flood of 1927 were harbingers for a looming catastrophe that may shake the very foundation of Blackness in America. With climate change and the potential of permanent flooding in those areas, we now face the prospect of Black History literally being washed away.

[rev_slider flood]

Black folks are children of the Flood. Like the ancient settlers of Egypt and the Fertile Crescent, we are tied to the black soils of our American ancestral homes by both the fear and reverence for the power of the mighty waters. The Mississippi Delta, a wellspring of southern Black culture pre-and-post slavery, is the most fertile and most broad of the wetlands that form the setting for much of Black history. But there are plenty more that are just as important – including places like the lush valleys and swamps from the Cape Fear in North Carolina down the coastal plain to Florida that were once known as the great Gullah, an area known for the rich syncretic history of the Geechee people. Many of the earliest free Black settlers fled the South and ventured to lands along the Arkansas River, which for a time was the natural boundary for American expansion. The most prominent of the local Black enclaves was Greenwood, known now as much for its Black Wall Street heyday as it is for the white riots that destroyed it.

The intimate link between Black people and the floodplain is indeed a defining part of American history. Most plantations, the major entry points of Black people into America, were along or near fertile wetlands, with their soils enriched by silt deposition from rivers. Free Blacks and slaves that escaped and couldn’t quite make it to the North often set up communities in the undesirable swamps in overflows around rivers, which at the time were malaria-ridden and still often impenetrable to whites. These areas were by definition flooded, and communities could only afford to be as permanent as the waters’ temperaments allowed.

Slavery was replaced with sharecropping. Freed slaves were forced out to the low-lying swamps and floodplains while being obligated to work the higher value lands of the former plantation owners. Flood lands were the incubators in which American Black history was formed.

But, by design, the histories and people that were incubated in these areas live in precarious situations. Some have already been submerged.

I grew up near one such place. There is a certain hill that rises like a natural crown among the low swamps on the south side of a bend of the languid, wide brown ribbon of the Tar River. Unbeknownst to many, that unassuming slope is the site of one of the keystone landmarks in Black American history; one of the wonders of the American landscape. It is on that hill where in 1865 freed slaves created the first Black-administered Black community in the United States. They called it Freedom Hill, and the town managed to endure despite white opposition and intimidation. Known later as Princeville, North Carolina, it continued in a line of unbroken existence to the present-day.

[rev_slider Princeville]

Princeville is defiance given form.[1] While the official position of the Federal government during Reconstruction was to encourage freed slaves to return to work with former plantation owners, with the protection of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Union Army, Blacks were able to build a community there at Princeville. As long as Black people did not own the flooded lands and remained in living conditions only a step away from slavery, Whites were at first generally content with the development of–even the eventual incorporation of–the town in its early days. But even with meager resources, many Princeville citizens still managed to create thriving businesses and develop a strong local political identity. Even the efforts of the original Ku Klux Klan, designed to brutally suppress the Black vote in the post-Reconstruction South, failed in Princeville, largely because of its solidarity and inertia.

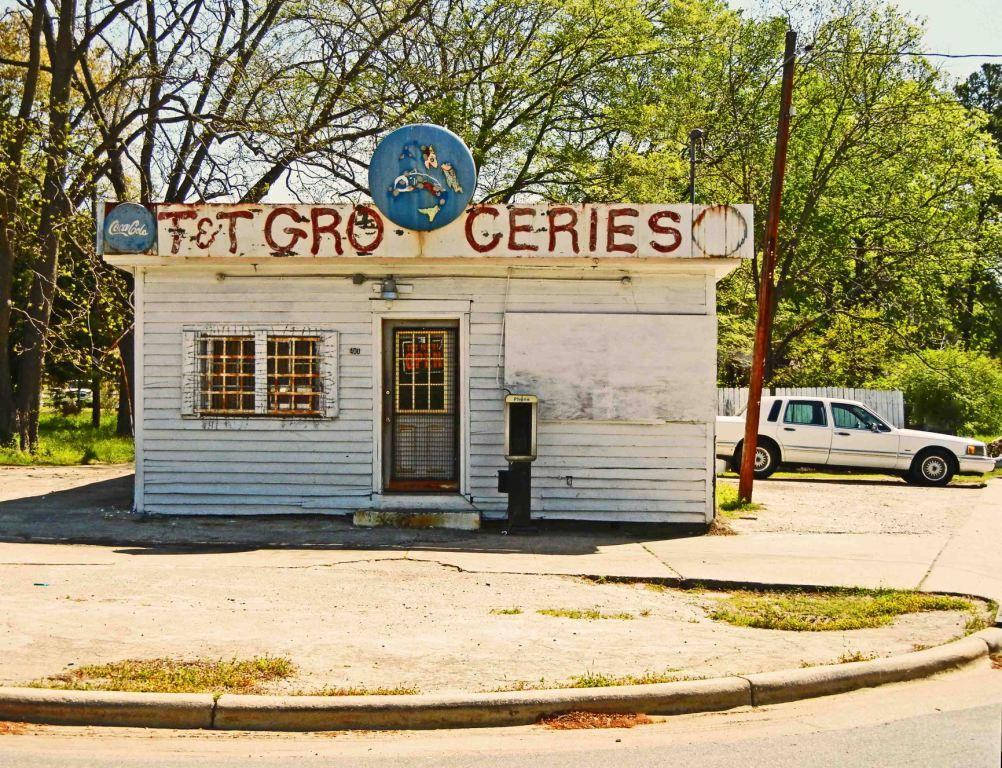

But, like in the rest of Black America, the 20th Century proved challenging to Princeville. Those forces of racism did become serious threats as segregation became codified in Jim Crow, violence began to eat away at the edges of the town, and the town charter was nearly revoked several times. The Depression and further economic crises caused waves of mini-exoduses from Princeville, and diseases and comorbidities that affect Black folks have always been hyper-represented. Still, people in Princeville manage to make it, as they always have. The convenience stores, the church, the Dollar General, the green cemetery, the schools, the individually owned shops and offices, and all of the people that make up the connective tissue of Princeville live a legacy of defiance.

The Tar River has been a threat to that legacy, perhaps even more so than even the Klan and the Depression. Princeville’s history has been punctuated by floods, and even heavy seasonal rains can cause trepidation there and in its larger neighbors, with the constant risk of flash flooding that I have experienced firsthand. A two-storm impact in late summer 1999 made those flash floods seem like trivialities, as Hurricane Floyd sent walls of water to ravage Princeville and the surrounding counties. The waters rose to 100-year flood levels and wiped out entire neighborhoods. Across two counties, Black families and communities living on floodplains were ravaged the most by the flood. Princeville is in Edgecombe, a majority-black county that suffered heavily for long periods of time. Edgecombe had the first FEMA trailers, and in some places their rusting, rotting metal husks still dot the landscape like the discarded shells of overgrown bugs.[2] Five years after the hurricanes I heard reports of Black families still drinking contaminated well water.

In Princeville’s case, most of the people came back after the waters receded. But the flood proved crippling in a way that perhaps even the renowned resolve of this community cannot overcome. The only local municipality in NC to have lost control of its finances to the state twice, Princeville is currently embroiled in multiple financial scandals and is dealing with high poverty rates in its virtually all-Black population. The town still floods at the slightest suggestion of rain, and the loss of vital wetland area nearby may be making things worse. The Great Recession already had Princeville on the ropes, and the vital loss of infrastructure, jobs, and property may have been the knockout punch. Nothing is certain, but the next disaster could very well be the last.

Princeville represents the entirety of American Black culture in a way. Founded on the dangerous land that Whites would not–indeed could not–inhabit, the Black settlers found a way to make the inhospitable hospitable. They found a way to turn the swamp into a home, and toiled to keep that home even as both the floods from the river and the overwhelming tide of racism threatened them time and again. Places like Princeville dot the landscape across the American South where feet, unshackled for the first time, roamed and tried to make do.

Many of the descendants of those first settlements like Princeville now live far away from them, and disasters like the Great Flood(s) combined with racism, poverty and the Klan’s ugly, hooded shadow to drive Black folks by the millions away from their homes. The story of the Great Migration is not only a story of Blacks blazing trails to the West and the North, but a history of them moving into cities. Even in 1917, years before the apex of Black movement, prominent Negro scholars like W.E.B. Du Bois noted these exact reasons, including floods specifically, as the main motivators for migration.

But just as Black folks found out the hard way that the cities like Chicago, Detroit, and New York would not yield so easily to the hope of economic advancement and social equality,[3] they also found out that the fearsome destructive forces of the weather were not yet behind them. Data on the disparate likelihood of Black people and other minorities to live in floodplains are conflicting, but poverty, lack of access to insurance, renting property, and housing in lower-value areas ensure that Black people are always among the hardest-hit whenever disasters like floods strike. The Black populations in the Northeast were hit just as hard by Hurricane Sandy as their white neighbors, but have yet to experience the same kind of recovery.

Of course, the descendants of those who stayed behind in the migrations still face the issue daily as well. Hurricane Katrina, the greatest socioeconomic and racial disaster of our time, sent a diaspora of almost 400,000 people fleeing from the Gulf region. But Black people are returning to New Orleans–many to the same likely-flooded areas as before. Even if the city can avert further Katrina-level disasters, the lesser floods and economic disasters will continue to take a toll on Black land ownership and quality of life, especially as the world gets hotter, the weather gets more extreme, and the oceans get higher. Across the South, ancient Black communities like the Gullah in South Carolina and Georgia, along with other coastal properties that have been stolen from Blacks, face existential risks from sea level rise over the next century.

Rich histories and existing people washed away in the deluge. Insect-borne illnesses like malaria, chikungunya, and the dengue resurfacing as wetlands get warmer and wetter. Climate change and sea level rise threatening the very foundation and existence of both Black lives and Black History. Without action, the ancestral sites of Blackness may become a collective American Atlantis.

As we struggle to awaken the American cultural consciousness to the fact that Black lives do indeed matter, part of whatever platform develops must be the climate and the physical environments that we live in. Environmental injustices may be properly viewed as socioeconomic and racial injustices. The inverse — that racial justice necessarily includes environmental justice — is equally true. Just as the floods defined our history, so they can wipe it out and take a good deal of actual lives with them.

The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation noted the unequal burden that Blacks face in a report that is now over a decade old. But the fact is that we’ve known it much longer than that. Ever since the first freedmen staked claims in the swamps, we’ve known. Ever since they built homes on Freedom Hill, rice riverboats in the Gullah, and settlements on the jet soil of the Delta, we’ve known. This is a disaster centuries in the making. Without action, the things and people we left behind may be destined to the oblivion of the “acts of God.”

[1] For a full early history, please visit http://digital.ncdcr.gov/cdm/ref/collection/p16062coll6/id/1453

[2] http://www.southernstudies.org/reports/Princeville-WEB.htm#_ftn1

Comments

Awesome read. Love the connection between historic landmarks and present-day black lives matter movements. Question: To prevent these landmarks from becoming an “Atlantis”, how can we go forward in educating people to recognize these landmarks and to preserve their legacy? Should these facts be taught in public school?