It is universally acknowledged that political and civil rights are hollow [without] economic rights, that economic and social rights without political and civil rights still may constitute slavery.

And so, our struggle goes on…The struggle for political, economic, and cultural selfhood and emancipation. The struggle of all the ex-colonialists against all the ex-imperialists.”

The old saying about sausages and congressional bills, how it’s better if you don’t see how they’re made? Movements are the same. There is nothing glamorous about the struggle. Big change is complicated, confrontational, wearisome. Stakes rise beyond expectation. By definition, adversaries of a movement are powerful, with seemingly limitless resources. Victory is rarely in eyesight, revolution always a tenuous and blurry goal.

And that’s just the external. There’s all the mess within, too – factions, resentment, and clashes. Tiny divergences of opinion that balloon into unbridgeable divides. Allies that turn out to be enemies. Eternal balancing of both forgiveness and skepticism.

None of this is avoidable – in fact, on the contrary. It is all actually inherent to the process of movement building, the required burdens of change. After all, the best and most just of us are flawed – mere mortals reaching for superhuman goals.

Speaking of movements – here we are. All the wide-eyed questioning of whether the current movement for black justice was “just a moment” was for naught. The movement for black liberation, racial equality, police reform – the call for critical restructuring, accountability, societal reckoning – is here to stay. There is no stasis here. The pressure will only mount. The streets will fill with more and more bodies, bodies that look like us. The demand for change will accelerate, even in the face of accelerated retaliation.

What a terrible time for Julian to die.

—

Almost fifty years ago my grandmother drives my father from Toledo to Bowling Green State University to see Julian Bond speak. It is November of 1968, a clear sky disguising the close to freezing temperatures. My father is 14.

At 28, Julian already has his hands full of accomplishments. He co-founded SNCC at 20, and was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives at 25. He won a Supreme Court case at 26. He was nominated for vice president at 28.

Even now my father can picture the room, filled with almost 2000 people. And he remembers standing up to ask a question, younger than everyone else. “I asked him about the 1968 Olympic Boycott,” my father tells me. That was the year black athletes were urged to not attend the games as a protest against America’s continuing discrimination, the same year Tommie Smith and John Carlos stood on the winner’s podium with their heads held down and Black Power fists in the air. “He said he supported it. He spoke out against Vietnam. He talked about the need to keep fighting for change.”

Afterwards my grandmother takes my father up to meet him, tells my father to introduce himself. Julian asks my father what his plans are. He tells him he should move to Atlanta and go to Morehouse. Four years later, he does.

—

“1968?” my dad says now. “That doesn’t seem right. I think it was before the Olympic boycott. Before King died, I think. And it was after Judge Crockett out of Detroit released all those people from jail.”

I google Judge Crockett. “That’s impossible,” I announce. “That whole Detroit situation happened a year after King was killed. And besides, that’s the only Bowling Green State speech I can find.”

The details are hard for me to visualize. Friendships in the current movement have mostly sprouted virtually, many people build initial connections through the internet. How did they manage to build a friendship, this college student from Ohio and the seasoned and precocious Civil Rights leader?

“Oh, I don’t know.” He thinks for a second, wrestles with fraying memories. “There was something on the Freshman calendar, I think. He was speaking or something. And a few of us went to see it.” Again, my father introduced himself, told Julian that he was the reason he had decided to attend Morehouse. Julian pretends to remember him even though he doesn’t.

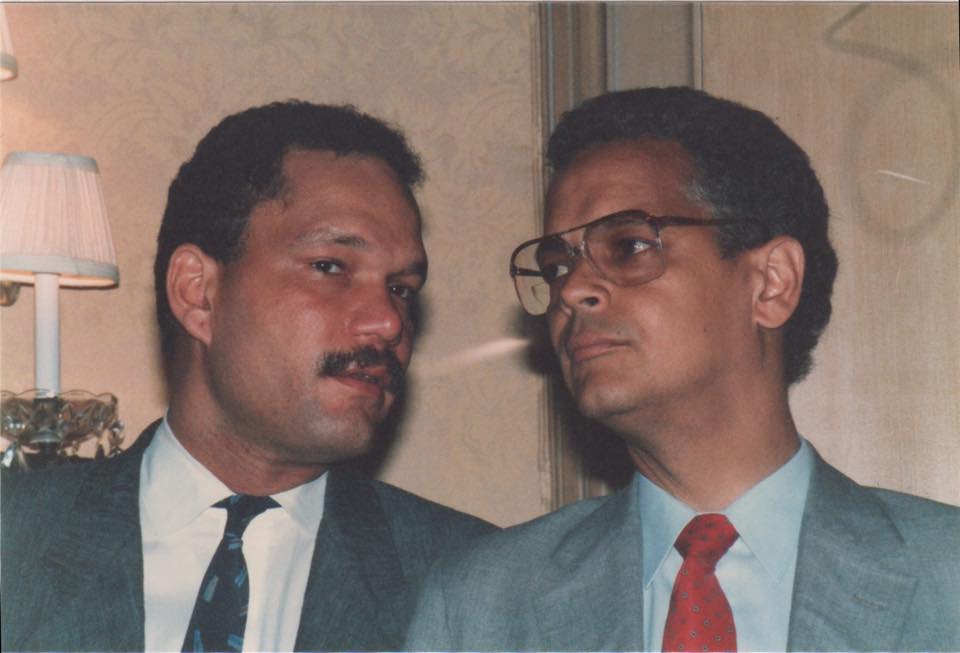

It’s hard for him to remember now exactly how it happened, he says. My dad kept reaching out. Part of it was admiration and interest – he understood the weight of Julian’s work, he wanted to fight for racial equality in the same way. But it was more than that. The two of them had similar senses of humor, impish and witty. Other things, too. “We both liked to go to the movies,” my dad says. “I remember going with him and his first wife to see Jaws, when it first came out.”

“The oppressed black people of this nation, quite probably in concert with the other oppressed colored minorities of this nation, [are thinking of] of building up and joining political coalitions. Now that is not easily done. It requires that there be an end to slogans and rhetoric and the beginning of action. It requires that someone – and in recent years this task always seems to fall to the young – begin now to organize the large masses of unorganized Americans.”

Last month I was in Ohio. The streets of downtown Cleveland were almost silent – empty except for the clumps of people heading home after an Indians game. A few blocks up a few thousand of us convened in Cleveland State University’s auditorium, everyone from some of the leaders and drivers of this movement to irrelevant tiny bit players like myself.

I can’t explain it all the way, except to say that it felt like home to be in this space with these people. It felt like freedom, like a victory unto itself.

This is a new movement and it looks different than it did on a cold morning in 1968 — the increased but not yet sufficient focus on gender identity and sexual orientation, the narrative presence of women, the Internet as the primary organizing method.

And yet, like any movement, it is not without complication. Outside of this space resistance grows louder. Inside this space there are still improvements to be made.

It is strange that the current iteration of the movement for black lives exists when it does. Many of the leaders of the Civil Rights movement are dead, the rest are old. Some are still working. Surely it is unfolding differently in their eyes, watching a new phase of their work take hold.

Most of the ones who’ve made it this far were the youngest at their time –John Lewis was chairman of SNCC at 23, Andy Young joined SCLC at 27. And even among the young, Julian was one of the youngest, plus he had that face that made him look perpetually fifteen years younger. How strange for the ending of men like Julian to play out alongside this accelerating new movement, each of them in the background of the other.

“What will be needed is what the great black man, Frederick Douglass, called for in another speech about 116 years ago. “It is not the light that is needed,” Douglass said. “but fire. It is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened, the conscience of the nation must be startled, the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed, its crimes against God and man must be denounced.”

I defer to those who have their hands deeper in the dirt, but my suspicion is even the most successful movements often fall apart. Tiny parts that require resculpting, bigger parts that are reborn and adjusted.

I have seen this movement as rooted in the same substantive fight as those that came before. But I have imagined the functional – the methods of organizing, the goals, the internal structure or deliberate lack there of – as entirely different.

But I’m not so sure that’s true. Perhaps they are more similar than I realized. There’s something to be said for being on the right side of history. It’s hard to break those ties. It has always brought me great joy to think about the grace with which Julian and John Lewis repaired their relationship – the fact that they were able to move past the lowest points in the effort to build something greater. That is what this movement is trying to do, too.

—

I did not think Julian Bond would die. Surely had I thought about it I would have come to the unfortunate realization that it was inevitable. It’s not old, 75, but it’s not young either. But somehow people like Julian seem above that type of tragedy.

A few days ago I started searching for the speech Julian made that late November day almost fifty years ago. The the speech was among Julian’s papers, housed at the University of Virginia. There was no electronic version but a request to the library landed me a copy.

All of these quotes are from that speech. It’s overwhelming to read his words now – to think about how much has changed, and more importantly, how much hasn’t. It makes me both joyous and sorrowful to imagine 1968. I can see my father watching him in awe from the audience. Last weekend, fifty years later he was helping his family spread his ashes in the ocean.

We think of movement people as serious and one-track minded, perpetually marching in the front lines. But such characterizations are childish. One-dimensional. He was a real flesh and blood person who spent a lifetime trying to build something bigger than himself. So much of what he said to my father as a child was not just observation but prophecy. I’m heartbroken that he’s not here to see what happens next.

Comments

nice post..

assignment