During a semester of my last year of high school our syllabus covered poetry. We were assigned Thomas Hardy, William Butler Yeats, Robert Frost, Walt Whitman, Shakespeare, Geoffrey Chaucer, Oscar Wilde and Alexander Pope. These writers had three things in common: they were all dead, they were all male and they were all white.

I was a decent student. I loved reading and writing. But I found my eyes scanning the lines of these poetry greats without a burst of recognition or affirmation. I had this idea that poetry should make me feel something, that it was something more than just the acknowledgment of an era in history. I figured that if I didn’t emotionally connect to the work, perhaps I was too young, too insignificant, too stupid compared to these poetry giants.

I was raised by my Punjabi-Kenyan mother and white father in Switzerland. At home I saw difficult power dynamics play out as my father asserted his white male dominance over my mother, constantly criticizing her for not assimilating into the whiteness of country we lived in. I saw my mother break herself for not being his ideal partner until he finally had an affair with a white woman and left my mother. And there I was a brown girl trying to squeeze myself into a box which I didn’t fit into, trying to just be less alone. So as I encountered the assigned reading, I found myself wondering… what do girls of color know about poetry? Nothing in our school syllabus showed me that we held the essence of poetry within our pain and love, or within the experiences of our black and brown ancestors. After twelve years of reading hundreds of poems, I eventually believed that beautiful words were only worth seeing if they came from the pens of white men.

At the international school I attended, most of our English professors were white and male. They chose books which they subjectively thought represented all the greatness of poetry. By doing so, they left out 70% of the students attending those classes. It is difficult to describe how alienating it is to never fully see yourself represented within the books that you are assigned in school, or to appear as merely a mention, a side-note observed through the white male gaze. If you are not a cis-gender, heterosexual white man, it can feel as if your perspective is of no value. It can feel as if you are simply there to worship without question at the altar of white male supremacy. The poetry canon represents the books deemed worthy of praise by other white men, so it is only natural that that canon often omits works by black or brown woman.

As an experiment please Google: greatest poets of all time.

Count the women.

Count the brown and black women.

After my first experiences with poetry in school, the poems I wrote in my own journals suddenly started to feel self-absorbed. I was scared that my perspective was irrelevant. Eventually, I stopped reading and writing poetry altogether out of self-doubt. My professors whitewashed our school syllabus and as a result I grew up thinking that my experiences and feelings were not worth reading.

When I started attending college, I was lucky to have brilliant, feminist professors who helped shape my perspective and exposed the ways in which patriarchal structures marginalize women and center male voices. I was increasingly exposed to how white supremacy works and I learned how systemic racism weaves its way through all of society’s institutions, including education and including our school syllabi.

This past winter I was recovering from the death of my dog, who to me was my child and a source of emotional stability. Every morning the sky was grey. Almost no sunlight filtered its way through the bedroom blinds. I would lay in bed, bundled in piles of blankets, and put off the inevitable. Every morning was a struggle. It felt like I had a pile of weights on my chest that I had to heave off of myself before I could get up, get dressed, and perform a standard of happiness that others would feel comfortable with. I felt increasing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, which isn’t unusual for survivors of sexual assault, and I was having a hard time finding outlets for my pain.

One grey afternoon in January, I was still in bed after spending the darker hours chasing nightmares and fighting anxiety. I stretched my limbs, moved my tongue around the dryness of my mouth and adjusted my eyes to the slivers of light illuminating the the patterns on the quilt holding me together. My husband was at work and I had no reason to push the weights off my chest that morning. I was scrolling through my Instagram page, scanning images of friends looking carefree and happy on beaches bathed in golden sun, when I saw this poem by Indian-Canadian spoken word artist and poet Rupi Kaur:

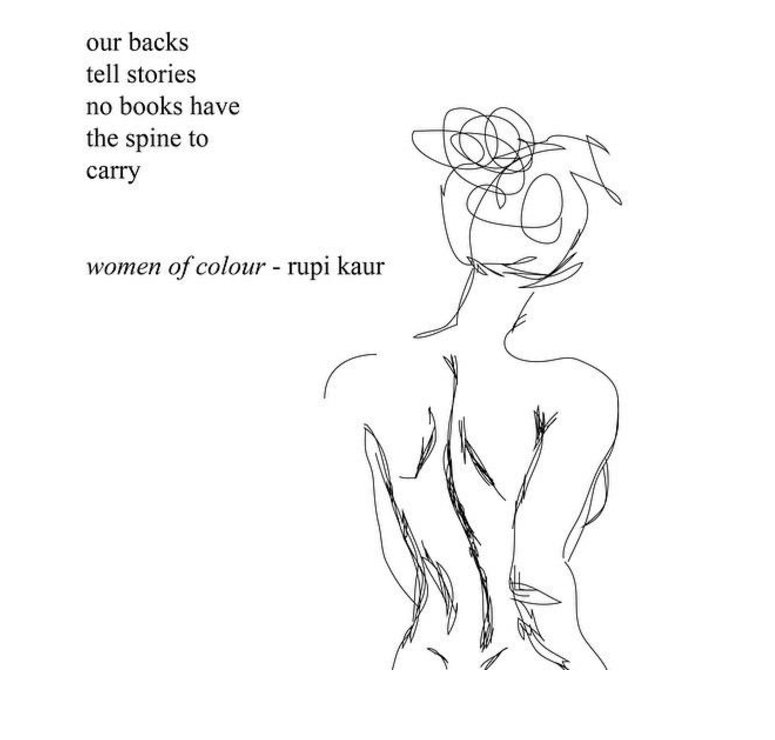

The words shot through my veins and I unconsciously let out a sigh of recognition. I had never felt a feeling of such powerful affirmation and recognition about poetry. “This is me! I feel this way too! I’m not alone!” It was like meeting my best friend, I could hug her and she could hold me as we both wept at our collective burdens.

I immediately bought Kaur’s book of poems milk & honey and absorbed every page, every word, every letter. I was finally reading about emotions I had felt before as a woman of color and as a rape survivor.

the rape will

tear you

in half

but it

will not

end you

— Rupi Kaur

These words by Kaur devastated me and helped stitch me back together in the time it took me to read them. The simplicity and directness of her poems, compounded with their structure, felt like the burn and warmth of bourbon working its way through my body. Reading her book helped me put words to my pain so that I could heal. I realized that our experiences as women of color were written. They were out there. I just had to look for them.

In order to find more of what I craved, I felt needed to depend on non-education based platforms, so I stepped away from academia. I couldn’t depend on universities to actively push for literature and poetry by women of color because in the United States alone, 84% of university professors are white and just 1% of professors are black women. I’m almost certain that we teach based on what we know and who we relate to the most. If professors teach by the canon, then women of color looking to read works by other women of color need to look outside of academia, I reasoned.

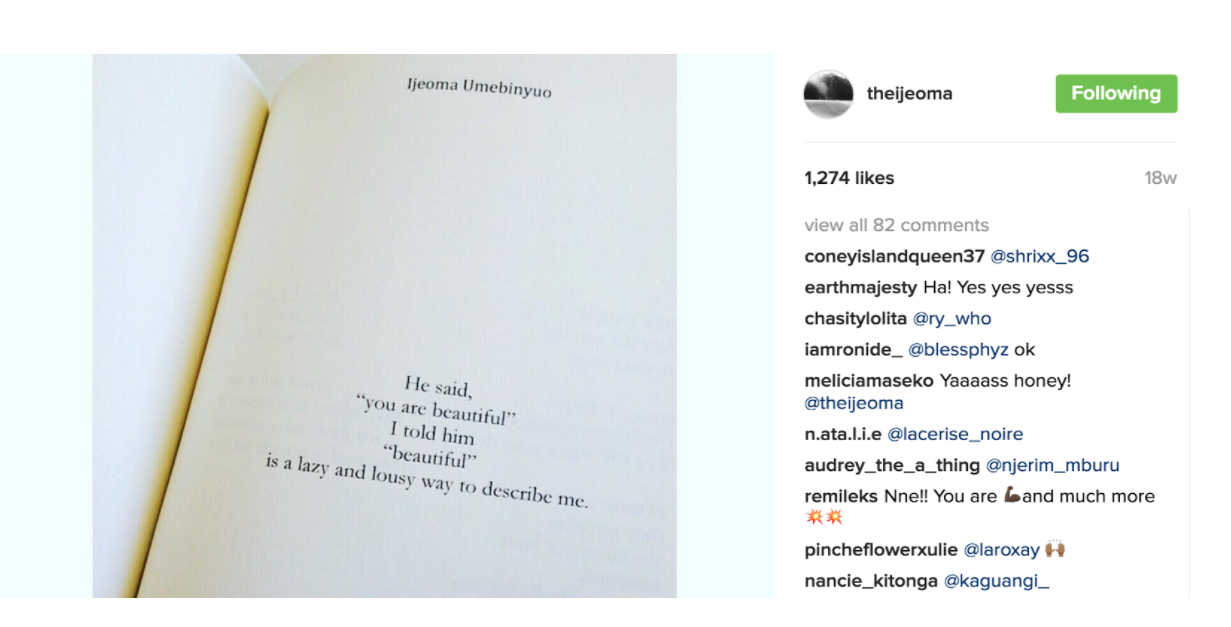

I was so hopeful after having found milk & honey that I expanded my search on Instagram and Tumblr. Black and brown women have been shut out of publishing and academia for so long that we’ve had to carve out our own spaces. Because we have easier access to self-publishing and online tools, it’s no wonder that Kaur built her base on Tumblr and expanded on Instagram, where she has over half a million followers. It was also on Instagram where I was introduced to Nigerian poet Ijeoma Umebinyuo and Bengali-American poet Ena Ganguly.

Umebinyuo and Ganguly both articulate the difficulties of womanhood and the alienation of being too different for both our homes and the rest of the world. I felt a strange comfort in knowing that I wasn’t alone in not fitting into patriarchal structures as well as the walls built by white supremacy. Reading their experiences through poetry helped me understand that our pain could be weaved into more than just that.

Much like Kaur and Umebinyuo who began with publishing their poems on Tumblr, Warsan Shire’s poetry exploded into our minds and ears when her poems were adapted for Beyoncé’s visual album, Lemonade. Shire’s work is robust, especially her 2011 collection Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth. Her writings are both healing and devastating to read; Shire taps into trauma unlike any other writer I had encountered before her. In Lemonade her words were cathartic for listeners who empathized with her voice: here is a woman who has felt the same pain as me, my pain matters, my pain is real.

The majority of social media users are millennials, so it isn’t surprising that writers and poets of this generation have changed the way that they reach their readers, especially for young women of color. Instagram’s users are 85 percent people of color, and a majority of users are women. Poems on Instagram are like affirmations in small, easy to share chunks. And the added benefit of seeing poets publish their works on platforms like Instagram is interacting with other readers, who form a kind of community. It’s amazing to see explosions of joy and connection from others who are also thrilled at reading poems they can relate to. These works have made me realize how much we still crave poetry, despite my earlier thinking that it was a medium which had lost its appeal generations ago.

I am grateful for social media platforms because women of color can finally have our voices heard without needing the gatekeepers of literary canons. We can expand our audience, and with that create even greater opportunities like having our works finally published in print. We can reach the millions of others like us who are so desperate to have our feelings and our stories heard. It is air in our lungs to finally feel like our experiences matter and that we are not alone.

But what does this mean for the black and brown girls in school? My hope is that as the social media popularity of these poets increases, there will be a shift in what works are included in the syllabi for both high school and university students. I believe that this would in turn require a shift in who is hired to teach: schools need to hire more women of color. I want to see the canon of poetry and literature change so that girls like me will see their experiences represented just as much as white children do.

I wish that the poems I had read at school could have made me feel less lonely, but it took a long journey to find the medicine I needed. Reading poems by women like Shire, Kaur, Umebinyuo and Ganguly have helped me heal my own wounds and also helped me realize that my perspective can take on multiple forms and perhaps also be received with relief, recognition and affirmation.

So what do women of color know about poetry? Everything. It is etched into our souls, our resilience, our pain, our happiness, our love; it is all of history.