The Cosby Show was never intended as mere entertainment. It was much more like Sesame Street teaching us letters and numbers, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood teaching us about make believe and Barney & Friends teaching us about feelings. Bill Cosby, from the very beginning, saw his role as a teacher assessing the problems of Black America and imagined he was providing solutions for ways out. The Cosby Show marks its historical moment but does not travel well through time or space. Cosby wanted a classy show, to present Black Americans as aspirational, as moving on to better things away from the dregs of working class social life. “No, there is a classy way to do things . . . I would rather hug and kiss and romance my wife as opposed to showing that we argue. I would rather show life in the positive sense. That’s the way I want to teach,” he said in an interview he did with Ebony in April 1985, right at the beginning of the show’s history.

Cosby wanted to create an experimental zone, with America as his classroom. Long before 2004 speeches about pound cake, name choices and police violence, Cosby’s opinions about working class life was articulated with clarity in the show. That is especially so, if we look through Cousin Pam’s character. And if we consider Bill Cosby’s magnum opus, The Cosby Show, from the vantage of Cousin Pam’s character, the show’s class politics and Cosby’s contemporary real-life choice of defense attorney Monique Pressley begin to cohere. That is, Cosby blurred lines between the fictive and the real, between the Show on the one hand and the world on the other, and my recent reflecting on Cousin Pam’s character made such blurring evident. A late addition to the show, Cousin Pam became the show’s most open avatar of its intent as an instruction in respectability.

Cousin Pam was the daughter of a single mother, a cousin of Clair Huxtable. But she was more than a character; she was also a vessel. Under the name and heading of Cousin Pam is a collection of ideas about class, race and gender that the show attempted to teach. These choices are supposed to be part of the same trajectory — a teaching tool, a guide for us to become better citizens, to make us docile and refuse to question things like sexual assault and violence, like classism and aspirations for wealth accumulation. This refusal to question was staged by the way Cousin Pam is utilized to teach lessons about life, love and money. They are intentional choices, choices that veil from view the truths of what bell hooks calls white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. So construed, Cosby’s desires to teach through television, the blurring of fiction and reality, anticipated postracial desires,wherein people are judged not based on the color of skin but the content of character. But the content of character here would be bound to one’s class. And in such a way, then, class is racialized. It has a color.

The entire show — all eight seasons — was about character content. From Cousin Pam’s vantage, viewers begin to understand The Cosby Show as a pedagogical tool, as a sort of After School Special that was supposed to teach primarily poor, working class Black America how to integrate into these United States.

The final scene, the very last moments, of the final episode of The Cosby Show open up a way to read back onto the whole of the series. As Heathcliff finally fixed the doorbell, a broken chime that was a running joke throughout season eight, he and Clair begin to dance, to circle and hug right off the stage into an audience of standing ovation, of cheers, of loud celebratory mood and melancholy that such an achievement in entertainment had ended. In those final moments of the final scene was a blurring between the real and fictive. That blurring is the way the show would be figured historically as well as thought of contemporarily.

The 1985 April issue of Ebony praised the show: “However, no one, not even the four-time ‘Emmy’ and five-time ‘Grammy’ winner Cosby himself, had any idea how always fickle television viewers would respond, for this show pointedly avoids the stereotypical Blacks often seen on TV. There are no ghetto kids or maids or butlers wise-cracking about Black life. Also, there are no fast cars and helicopter chase scenes, no jokes about sex and boobs and butts. And, most unusual, both parents are present in the home, employed and are Black.”

The show was praised, constantly, for what it was not…the content of the show never stood on its own but was about a reflection of some other thing, some deficit found in other depictions of black life. Cousin Pam was written, through a similar kind of display, by being everything the Huxtable children were not. So we learn through the character content of Cousin Pam that the Huxtables are people of good stock, they pay their bills on time, they have an abundance of food to be shared, they have an excess of space to be used by anyone. They have cranapple juice to spare for Cousin Pam and her friends. We also learn through Cousin Pam that folks from her neighborhood don’t understand the rules of sharing and caring, must be taught things like curfews and how to value homework and, importantly, what love means. Cousin Pam was everything the Huxtables were not and any semblance of normalcy was gifted to her through her adjusting to their way of life. Cousin Pam was an empty vessel, waiting to be filled with morals, ethics, values of the aspirational class.

**

Cousin Pam. I watched the final two seasons of The Cosby Show in a week, 51 episodes that amounted to a bit over 16 hours in television watching total and, having watched I can say I like her particularly because of her interactions with her friends Charmaine and Lance. I’d be lying to say I didn’t laugh at the wittiness of the banter, the chemistry with which the characters played off one another. Yet I have major concerns regarding what Cousin Pam and her friends were supposed to mean in the show, the image and symbol they were supposed to represent for viewers, the content of their characters.

Appearing first in 1990, season seven, episode four, in an episode titled “Period of Adjustment,” the intensity and intentionality of the education Cousin Pam and her friends receive in just over 21 minutes is astounding. After moving into the Huxtable residence and being amazed by the spaciousness of the living room, Cousin Pam — as she is continually called by Cliff throughout her two seasons’ appearances on the show — is given a series of lessons. Her first appearance on the show, she learns the lesson of family after discussing the large space of the Huxtable home:

Cousin Pam: Oh man, this … oh, this is nice! Real nice! Yes, nice and large! But not too large, just the right kind of large, you know? Larger than our apartment, that’s for sure. Not that our apartment is small, it’s just…just not this large. I’m talking too much, huh?

Clair: Oh no, you’re fine.

Cousin Pam: I mean, this is just the living room! You could take our apartment and put it in this living room. No, I’m lying, no. You could take half this living room and put our apartment in…

[…]

Clair: Listen, big or small, this is your home and there’s a lot of love in it. And we’re very honored and blessed to have you here.

[row]

[column size=”3/4″ center=”yes”] [/column]

[/column]

[/row]

Later, she learns that placing labels on food is improper because all of the food in the house belongs to everyone. She learns, in other words, how to share. When speaking on the phone with her boyfriend, she says that — yes, indeed — the Huxtables have and actually pay for cable television. Her boyfriend appears — Arthur “Slide” Bartell, played by Mushond Lee — also making much ado about the large home. Where they come from, there is nothing nearly as spacious, as big. Charmaine Brown (Karen Malina White) and Lance Rodman (Allen Payne) – who both seem like very good people to have around as friends – too, were impressed by the large home. Unlike the stifling conditions from which they come, there is not only space but abundant love, there is not only space but an ethic of sharing, things that Cousin Pam had to learn from those of the propertied class.

When Cousin Pam wants to attend a party in the Bronx, her newfound 10pm curfew is an obstacle to be overcome. (Implied is that she did not have a curfew while living in the home with her single mother.) Trying to break the curfew with her three comrades, Cousin Pam is caught by Cliff and Clair. After being caught, she and her friends are given a lesson that one does not “take the punishment” without knowing what it would be, but that one should be “responsible.” Her friends are chided for not caring about her because if they did, they would not have put Cousin Pam in such a situation wherein she had to decide between following rules or breaking curfew. Cousin Pam is introduced on the show through a series of lessons about the right way to abide with others. Everyone needs to learn something from the Huxtables.

In “Attack of the Killer B’s,” Cousin Pam learns from Theo Huxtable the best ways to study. Cousin Pam is beginning to be concerned about her future, something – it is at least implied – she did not think much of before spending time in the Huxtable household. With this newfound space is a newfound freedom to think about possibilities for flourishing, so the story goes, and studying for high school tests is part of that narrative. There is a normative striving that the episode – like all episodes with her as the main character – presents as necessary. Learning to study is part of that striving. She learns tips and suggestions from Theo and not from Charmaine. This instruction from Theo is of note because Charmaine, though her best friend, had been following the same patterns for study that Theo suggested without ever talking to him. How could they be best friends yet not ever talk about desires for the future, desires for study? How could they be best friends in the same courses but not attempt to help each other with ideas and suggestions? What was the content of their friendship if they could dance together, laugh and joke together, but not share ideas about the world, about learning? It wasn’t until the Cosby household and their class aspirations that Cousin Pam’s very friendship with Charmaine moved beyond what is considered to be the frivolous, the fun.

In “Pam Applies to College,” there is general disbelief voiced through noise and laughter of audience members appended to her desires for higher education. Cousin Pam’s study habits and failures are the butt of laugh-track jokes, her low grades and SAT scores are about her personal moral failings. In a meeting with the school guidance counselor, they had the following conversation:

Mr. Bostick: Pam, the grade point average for those schools is 3.7, your grade average is 1.9.

[audience laughter]

Cousin Pam: Mr. Bostick, it’s my understanding that these colleges look at a little bit more than just your grades.

Mr. Bostick: Well, now that’s true. But they also look at SAT scores.

Cousin Pam: Yes! SAT scores! Now, standardized tests, that’s me.

Mr. Bostick: Pam, you got a 750 out of 1600 when you took them last spring.

[audience laughter…again]

But Cosby and his show, through Cousin Pam, didn’t only teach about large spaces and good study habits. The show also attempted to discuss sex, attempted to tackle sexual behaviors. “Just Thinking About It” is a two-part episode in which Cousin Pam states that she enjoys the Huxtable rules because they give her structure, asks Cousin Cliff and Cousin Clair what it means to love and, eventually, asks Cousin Cliff for a prescription for birth control pills. Cousin Cliff’s response, we might say, is progressive. He says that if Cousin Pam’s mother agrees, he will give her a referral to a gynecologist that works primarily with young women. And Cousin Clair gives her a lesson about love, about sex.

It’s not that young people should not ask questions regarding safe sex and ways to protect themselves against STIs and unwanted pregnancies. And indeed, young people should be able to look to adults as models, as persons to ask questions and seek guidance. Yet, what is curious are the ways these various concerns – from space and sharing, to sex and sexuality – play out through Cousin Pam, how the content of her character is the one by which these explicit concerns regarding sex, sexuality, sharing, caring and love are rehearsed in and through.

So the “Period of Adjustment” was not just about her getting acclimated to new rules and behaviors. Cousin Pam was the prism through which we, as audience, were supposed to learn what it means to be good, moral, upstanding members of society, those that had not yet – but desired to – attained the social and economic status of the Huxtables. Cousin Pam and friends were a cast of divergences, the enfleshment of radical difference and distance, that had to come under the heel of the Huxtable household, under Cousin Cliff’s cool and Cousin Clair’s calm voices of explication. Cousin Pam is a collection of ideologies antagonistic to Black middle class aspirations, ideologies that must be remediated, renounced, in order to be a good, upstanding citizen. Through her, viewers obtain a sense of the class politics of the show itself.

**

Titles are important. Each time Cousin Pam called their names, they were Cousin Clair and Cousin Cliff. To Cliff, she was almost always Cousin Pam. Was her title stressed because we would have forgotten that she was not a daughter? Was it that viewers would have somehow imagined her as integrated fully into the family? Was each reference to her as Cousin Pam a way to continually mark her, and her friends, as difference? It makes sense, these titles, if the show is a pedagogical tool, if the show is about teaching us, if the show is about images and symbols. The titles to me suggest not a family but a keeping-at-a-distance relation, relation based on functions people serve that are sometimes, though not necessarily, about love. The titles are reference points about roles, about images and symbols.

The titles cue us in to an uninterrogated idea in The Cosby Show, an uninterrogated idea that does not, however, remain only on the show: that the obtaining of degrees and “good jobs” are — of necessity — good, positive, beneficial. Presumed is that because marginalized peoples have been kept from such spaces of education and labor that inclusion is, of itself and necessity, a moral and ethical success. But like Martin Luther King, Jr. suggested to Harry Belafonte, perhaps we need to be as concerned about what those things are in which we desire inclusion and integration as we are concerned about being included itself.

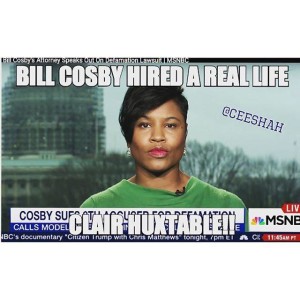

In recent discussions of the accusations levied against Bill Cosby, there is public celebration of Monique Pressley – attorney, minister, radio show host, managing partner of a law firm, professor – because she mirrors the savvy, the rhetorical aptitude and capacity, of Clair Hanks Huxtable, a celebration because of the titles she assumes, because of the images and symbols she fulfills. Like the desired blurring between the fictive and real towards which The Cosby Show aspired, some offer that Pressley is a “real life Clair Huxtable.”

[row]

[column size=”3/4″ center=”yes”]

[/column]

[/row]

With the meme placing Clair Huxtable next to Monique Pressley, one person even offered the following theory: “Bill planted a seed for his own defence [sic] with Clair Huxtable, on The Cosby Show. I’m not saying he did or didn’t do what he’s been accused of, but I had to shed light on what I do know he has done for my people and will certainly be showing The Cosby Show to my kids as they grow up.” There is a belief in the moral fitness and the moral compass of Cosby because of the blurring of the fictive and the real, and this blurring comes with proliferation of careerism alongside the moralizing against working class black social life. Bill Cosby, it seems, chose Pressley because of the image, because of the symbol, and this consistent with the way Cousin Pam is used to make a point to viewers, the way Cousin Pam is a prism by which we can aspire to be better citizens, upstanding, integrated into these United States of America without reservation, without interrogating the very desire for such inclusion.

The Cosby Show promoted an acceptance of the political economy, in other words, without qualification. This acceptance was promoted, for example, by the assumption that a job itself — as an attorney, for example — is a good and moral and ethical choice, that it serves to benefit all of Black America. And this by virtue of the salary that one stands to earn because of such a job. We should not, it seems to me, forget that Vanessa’s fiancé was not accepted by Cliff until it was discovered that he wasn’t just a maintenance man but the head of maintenance for the university and, importantly, that he owned property. He was accepted because of what he could provide in terms of class; his class status was the content of his character. The same is true for the ways Pressley is considered, that because of what she has achieved — without any regard to the ethics guiding such achievement — that she and her achievement are well and right and good. There is a mixing of the fictive and the real, of Clair and Monique, that is grounded in a desired relation to the economy, to the ability to make money, to home ownership and careers.

But if the work you do does not take into account the ways it can reinforce marginalization and stigmatization, that work should be interrogated for what it likely is: a means to a financially viable end. And this financial viability does not present to us justice, but is part of the foundation of inequity. It is integration into, rather than a disruption of, white supremacist capitalist patriarchy with all its trappings of power.

We who are not the children of the black elite, the privileged class, are what Cousin Pam represents. Those of us that attended public schools in urban areas that were likely under-resourced. Those of us who only see “stable relationships” in the lives of extended middle-class family with well meaning, not-too-sexual children—we are Cousin Pam. We who come from so-called “broken” homes with working single mothers. We with hypersexual friends and potential lovers. Those of us racy enough to ask blunt questions about condoms and birth control all, we are in the position of Cousin Pam. We are all Cousin Pam.

Cosby’s television series as well as his contemporary choice of attorney are both about the symbolic value of the image, not about producing anything along the lines of truth or justice. If we actually care about the cause of truth and justice, what will be necessary is a recasting of desire, a way to think along with the social life and love of the many discarded and discardable, those that are supposed to learn from the black bourgeoisie. We have to interrogate the idea that the propertied class occupy a moral and ethical zone that should be desired. Cousin Pam had value before entering into the Huxtable household. She and her friends do not need to learn how to be moral agents in a Brooklyn brownstone.

Comments

WONDERFUL article! Enjoyed it emensely…. “Cousin Pam is a collection of ideologies antagonistic to Black middle class aspirations, ideologies that must be remediated, renounced, in order to be a good, upstanding citizen. Through her, viewers obtain a sense of the class politics of the show itself.”