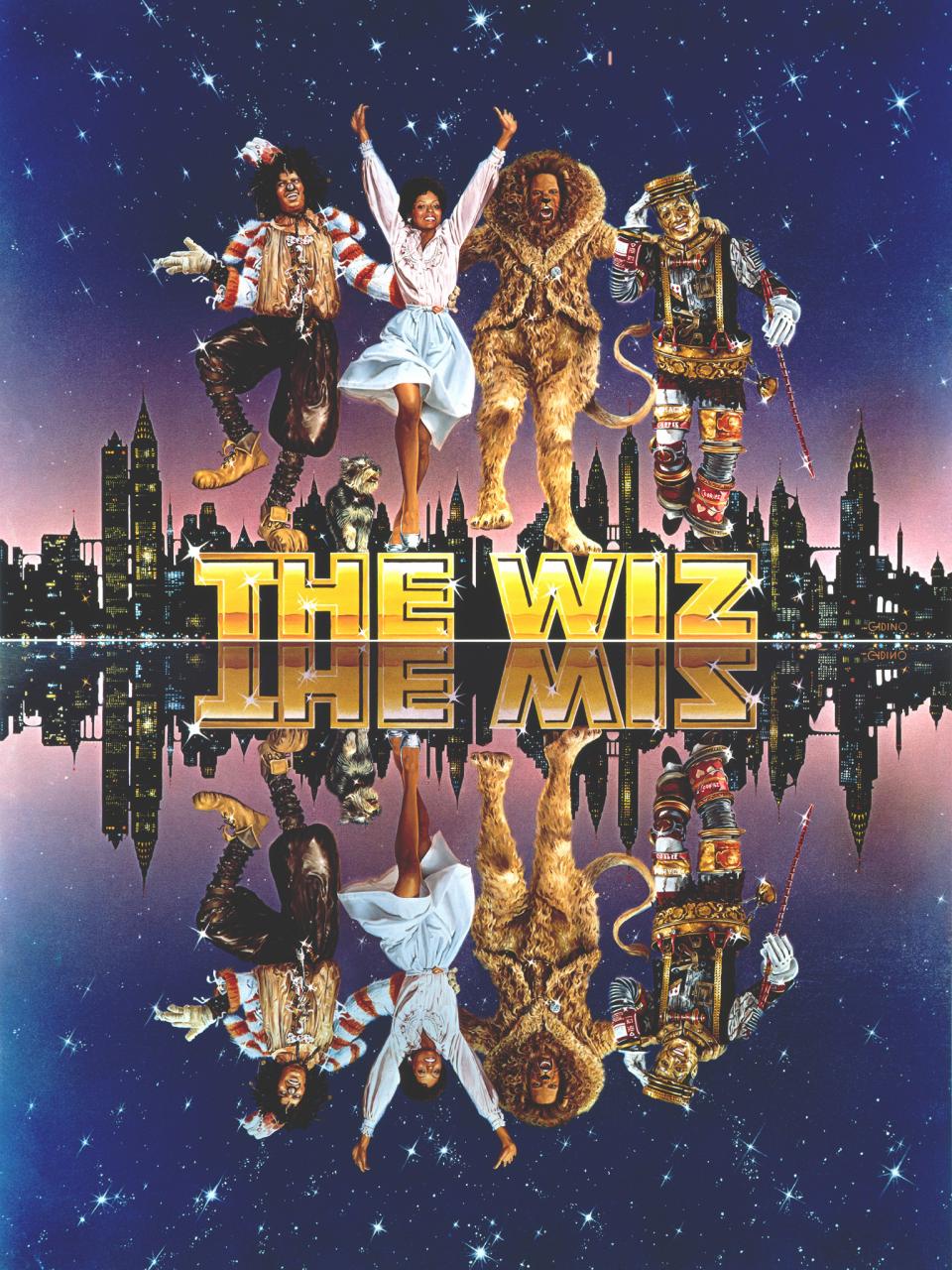

The Wizard of Oz is, as the saying goes, as American as apple pie. Every year at least, I’d crowd around a screen with family to watch Dorothy’s teleportation from sepia-seeped Kansas to technicolor Oz, a tradition that I imagine many American families share. However, my family shared another tradition that many others did not. We would also grab popcorn and sing along to our favorite songs in The Wiz, the Wizard of Oz’s pro-Black stage-turned-film adaptation. Very few films have ever influenced my sense of what is and what could be as this simple subversion, and after watching NBC’s live televised revival the reason why has become clear to me: The Wiz, especially the film version that I am most familiar with, is a masterpiece of Afrofuturism, science-fiction and fantasy, salvation and humanism; and it reflects the best of what the Black collective consciousness can create.

Afrofuturism is a slippery concept. Generally, most science-fiction works written by, featuring, or focused on Black people are included in the umbrella. However, as a cultural signifier afrofuturism is something more than just futurism or science-fiction with a palette swap; a one-for-one re-casting of the original along racial lines with no added context. Afrofuturism is a cultural movement of resistance–because imagining future and alternate worlds with Black peoples is both a literary, artistic, musical, and historical revolutionary act–mostly focused on the alternate worlds of science-fiction and fantasy. Imagining Black cultures and peoples who live in fictional worlds beyond our own and imagining ourselves in them is the spirit at the core of Afrofuturism.

Contrary to what popular culture seems to think, The Wiz is itself also not just a palette swap of The Wizard of Oz. Any re-casting of an all-white work, regardless of whether the script or setting changes, is in itself a political statement that changes the dynamic of how the work is consumed and digested. In The Wiz’s case, the animating spirit is rebellion, and that rebellious nature subverts and repurposes via alchemy the messages of the original film and its namesake book into something both about the Black future and the Black past.

The discussion about what The Wiz subverts and creates starts with the material of the first source. L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is thoroughly a fantasy novel, although the film version tries to tone down some of those leanings. The world of Oz and Munchkinland, with its flying monkeys, talking animals, wizards, witches, self-aware flowers, and evil trees is undeniably fantasy, and it gets explored in such depth through Baum’s and later Ruth Plumly Thompson’s sequels that it can aptly be described as epic fantasy, a world rivaling that of Narnia or Middle Earth. However, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz also blurs the line between fantasy and science-fiction, envisioning a quasi-steampunk world of animate machines and robotic Tin Men, balloons, and technology masquerading as magic.

The Wiz film takes themes from the stage version and builds on them to create a blended fantasy and sci-fi world that is at once evocative of the Black urban condition. Here, Oz is a fictionalized New York and the film’s Munchkinland is Harlem through an urban fantasy lens, tagged with graffiti and bounded by presumably busy highways. The Wicked Witch of the East (here, the Parks Department Commissioner) is a stand-in for white governance. This world is even more overtly steampunk than the original’s, featuring a polluted, industrialized city world where factory labor is enslavement. Evillene, the Wicked Witch of the West of this story, runs a totalitarian slave state that is both representative of the Black past and comparable to some of the great future dystopian settings in fiction memory. This setting is where the spirit of Afrofuturism truly flourishes and transforms.

The plot of The Wiz is also a deeply Afrofuturistic spin on the original. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is perhaps the enduring American fantasy novel, and Dorothy’s epic journey home occupies an important corner of the American mythos, reflecting and warping several themes of Americana. The film version of the The Wizard of Oz is a little bit about individualism and the ideas of white privilege and destiny at its source. Dorothy, an altogether unqualified conqueror, conquers Oz nonetheless through her spirit and determination, along the way committing several accidental murders, becoming a savior, and leading a band of misfits on a journey of self-discovery. This is not intended to be a cynical reading of a classic, but a notice that it helped create a strong tradition of endearing white heroes whose main qualification seems to be their grit.

These themes are amplified, enriched, and further subverted in The Wiz. Scarecrow, first Hinton Battle’s stage version and then Michael Jackson’s colorful film version, becomes a play on Black hopelessness and oppression while embracing a history of Black showmanship and music. The Tin Man is a story of Black emotion and the Cowardly Lion under Ted Ross’ show-stopping portrayal becomes a commentary on Black masculinity. And through it all, Dorothy’s story is transformed from that of a somewhat flat and unlikely gentile conquering heroine to a complex person who struggles with her own identity and fate while helping throw off a symbolic form of slavery. This is Afrofuturism at its core: taking the bones of an imaginary world built on exclusion and breathing into them the spirit of Black struggle and identity.

The Wizard of Oz is also a little bit about atheism and humanism. This is the strongest theme in the original, which endeavors to destroy the deus ex machina, both from a literary and social commentary perspective. The titular wizard is proven to be a fraud, an insecure man using a campaign of propaganda and inexplicable machine superiority to create in himself a God, and his unveiling is a symbol for modern religious (or anti-religious) awakening. The revelation that Dorothy herself maintained the power to shape the world and to go home all along reverses the god-human complex and proclaims her power as an ordinary person. This is an early humanistic sentiment, or at least one that breaks with the Western idea of a singular divine external God that must be reached via some conduit. It is clear that this portion of The Wizard of Oz at least is subversive and that the film version is almost a Trojan Horse embedded in the same old rote god-loving Americana that audiences cherished more and more as time progressed.

To me, the strongest part of The Wiz is how it takes that humanistic message and imbues it with a spirit of Black salvation and even gospel that complement the message instead of overpowering it. That’s no small task: it’s hard to pull off a statement questioning the legitimacy of divinities while also applying the Black divine tradition to humanism. The revelation that the Power was always in Dorothy and was something to be claimed by self-determination and the building of a new Oz as a Black wonderland through collective work–these are profoundly pro-Black and Afrofuturistic statements. While most of my reflection here is about 1978 film version of The Wiz, the theatre versions and the recent NBC The Wiz Live! versions bring out the gospel and salvation aspects most clearly. That message of self-determination and of building better worlds reflects the meta-political message of making The Wiz and the one that grounds Afrofuturism: if we ain’t in it, build a world where we are.

This reflection was given the clarity needed to write it by The Wiz Live! I recognized it as an old friend and began to wonder why–aside from basic nostalgia for the 1978 version I loved–it moved my spirit and made me feel it so deeply. I realized that The Wiz helped give me the keys to create, in the way that I imagine The Wizard of Oz sparked the imaginations of children for the greater part of a century. While I didn’t have the language then, what is clear now is that The Wiz is a revolutionary statement using Afrofuturism as its font-face. And today, as the subgenre and the literary and arts revolution that it represents finally begin to move from the corner to the main street, it is most necessary to honor it as a forerunner and also as a sign of what we can achieve in these media in the future.

Comments

Great points here and overall, an educating read. Afrofuturism is definitley an interesting concept.