[x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 45px 0px 45px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_author title=”About the Author” author_id=””][x_text]A long trip south on the Red Line train in Chicago is a pretty good way to get to know the city’s storied institutions of higher education and the role they’ve each played in the enduring racism that has so shaped my hometown. You might begin at the Fullerton stop, home of DePaul University, to which Mayor Rahm Emanuel cheerfully allocated millions of city dollars for a new stadium at the same time as he was closing 50 mostly-black public schools and 6 mental health clinics in the name of budget woes. Head south to the 55th/Garfield stop and check out the University of Chicago, my alma mater, entangled in everything from restrictive covenants and “urban renewal” projects designed to push away black residents, to a 2005 “ghetto party” that took place in a dorm where I was the only black resident, to a bunch of racist fraternity emails leaked to Buzzfeed just last week.

And then you get to the 95th/Dan Ryan stop– the end of the line. This is where one institution, Chicago State University, is trying to undo the legacy of the city’s structural racism. And that institution is in a lot of trouble.

Even if you’ve never heard of Chicago State, you’ve heard of Chicago State. Kanye West’s mother, Donda West, was an English professor there (and, for a time, chair of the department) from 1980 until her retirement in 2004; Kanye was enrolled there before becoming the college dropout immortalized in The College Dropout. Gwendolyn Brooks, the acclaimed poet who was the first black person to win the Pulitzer Prize, taught there, and the school named a center for literature and creative writing in her honor.

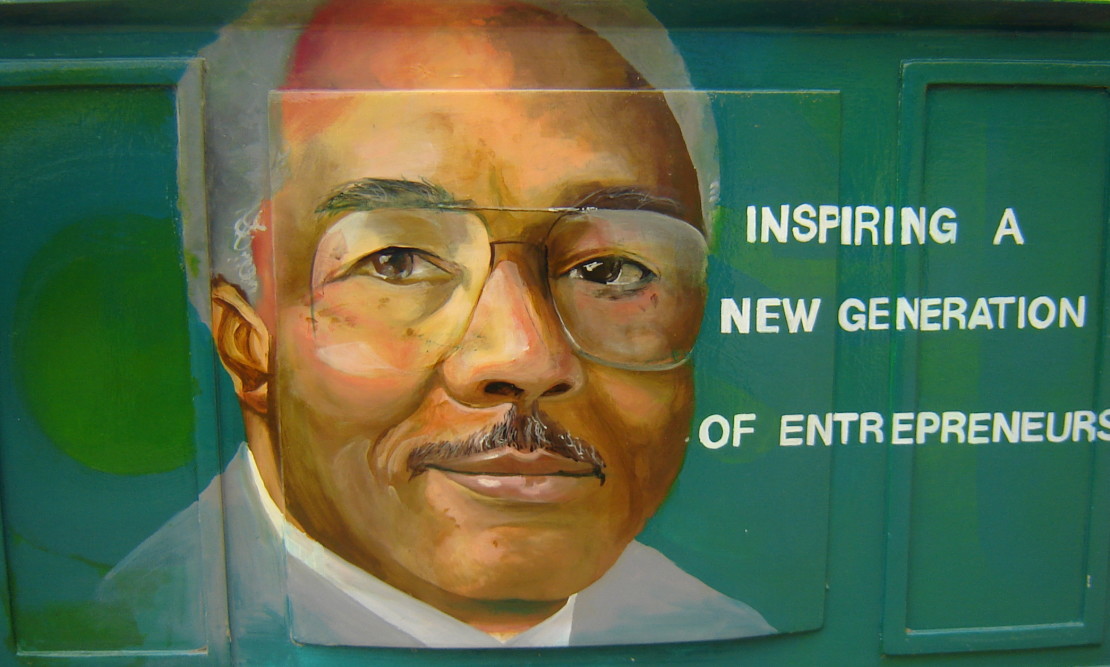

Chicago State is over 85% black (and 5.4% Latino, and 1.8% white), but while it is a predominantly black university, it cannot be designated as a historically black university. Rather, the school’s demographics changed as the South Side changed. Chicago State moved to its current location at 95th and King Drive just as the surrounding community, Roseland, was seeing the simultaneous departure of the steel and automotive industries and the white residents who once lived there. So while the school is a member institution of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, it doesn’t benefit from the cultural cachet of being called an HBCU. [/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 45px 0px 45px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/2″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_promo image=”https://sevenscribes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2053738043_1f1ca5a9f3_o.jpg” alt=”Courtesy: https://www.flickr.com/photos/67166696@N00/2053738043/in/photolist-afoUcK-afrGCo-afoUma-afrGrf-48tWLB-48xZ7L-6pTmgS-afoTZK-ydQ3iT-afoU5Z-48tWVn-48tWNk-yw54LK-vaXDq-6bw6Kw-48tY6T-bKqfC-48xXzY-48xZ1y-pN6KUe-pNkrnF-pvTtfj-pvWaz5-pvW9X3-pvTrp5-pNknwz-pNkmKV-pNkm2F-pvQKHr-pNpBhj-pNpAwS-pvW4UN-pvTWYe-pvTWrn-pvQFug-pvW2Hd-pNkfut-pvTUde-oRwJeT-pNkepT-pN6wZr-oRwGW2-pNpuDQ-pvTg71-pvQB5K-pN6ui4-pLeK9C-pNk9Sr-pvTN1z-pNppUQ”][/x_promo][/x_column][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/2″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_promo image=”https://sevenscribes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/3552082160_2d00d99d05_o.jpg” alt=”Courtesy: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vinzcha/3552082160/in/photolist-afoUcK-afrGCo-afoUma-afrGrf-48tWLB-48xZ7L-6pTmgS-afoTZK-ydQ3iT-afoU5Z-48tWVn-48tWNk-yw54LK-vaXDq-6bw6Kw-48tY6T-bKqfC-48xXzY-48xZ1y-pN6KUe-pNkrnF-pvTtfj-pvWaz5-pvW9X3-pvTrp5-pNknwz-pNkmKV-pNkm2F-pvQKHr-pNpBhj-pNpAwS-pvW4UN-pvTWYe-pvTWrn-pvQFug-pvW2Hd-pNkfut-pvTUde-oRwJeT-pNkepT-pN6wZr-oRwGW2-pNpuDQ-pvTg71-pvQB5K-pN6ui4-pLeK9C-pNk9Sr-pvTN1z-pNppUQ”][/x_promo][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 45px 0px 45px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]For generations of black Chicagoans, it has been known as a school of second chances. Of all African-Americans in Chicago receiving a bachelor’s degree from a public Illinois university, half come from CSU. The majority of CSU students are transfer students, entering with credits from community college or another institution, and many are older, are parents, or have been involved with the criminal justice system. In other words, the university serves the students least likely to enroll in and complete a four-year degree program. CSU provides these students with an affordable, accessible path to a bachelor’s degree, and many retain on-campus employment while they are enrolled. The university is also positioning students to be successful in potentially lucrative careers where African-Americans are underrepresented: it ranks top in the state for degrees awarded to black graduates in the sciences, maintains a pre-freshman enrollment program to prepare interested students for a major in engineering and science.

Despite this vital role, CSU has found itself under threat in the past few months. The state of Illinois has been operating without an approved budget since July, when GOP Governor Bruce Rauner and Democrats in the state legislature reached an impasse in negotiations. With no budget, state-funded services have been hurting, including home-based care for seniors, afterschool programs, and rehab centers for people struggling with addiction. It also means that none of the public universities in Illinois have received any money from the state for two-thirds of the fiscal year.

University presidents have been expressing concern since a year ago, when the governor first proposed a 31% cut in their funding. But now, the issue is officially a crisis. Last week, Chicago State declared a financial emergency. The school relies on state funding for about 30% of its budget, and the school’s president has told reporters that operating funds may run out as soon as March.

CSU students, faculty, and administrators refuse to go quietly, and have been united in trying to call more attention to the issue. Some express frustration at the relative lack of attention they have gotten beyond the community, even as campus racial justice issues at schools like the University of Missouri, Princeton, and Yale are still fresh in our collective consciousness.[/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 45px 0px 45px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/3″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text class=”center-text “]

95thtoHoward by Immanuel Sodipe

Mothers, I see always.

They be on the red line.

They fuss always.

Tell they kid:

don’t end up on the red line.

They was probably red lined.

They parents

ain’t have

mammas that work

‘cause they want to

or Christmas lights

or folks driving

past to admire.

So they mad.

They fuss.

They tell they children things

like: don’t end up

on the red line.[/x_text][/x_column][x_column bg_color=”” type=”2/3″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_image type=”none” src=”https://sevenscribes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/8393249436_d2c2e7bace_o.jpg” alt=”Courtesy: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vonderauvisuals/8393249436/in/photolist-dMFADb-8ZNd93-daepSD-53J8gV-5fctJJ-oauEq-6rPAv2-9vFg36-NVKrE-bHTnSa-78qTKR-oTEf4r-dV3fSt-kee24-pwduWx-6Hh2y-6pYtK3-qAcU9P-cQiYXE-4aiuvi-5hf4fj-5tFwKC-8Af8Kd-29yUuw-gTpWR6-pqBAhD-6Ttk9P-qAq1oF-8miLgs-qBKtAH-gTqyS2-8AbYSr-8367w1-aRXUZ6-bvrpPY-5aAq3K-5ZKAHi-bvuyNh-5b91xz-5WDuUj-5VF3Ht-xTJBh-64N3Fh-23srpw-5KbWH1-jADSqd-5WmmsY-7fQLQF-4ZFg5g-3HbJte” link=”false” href=”#” title=”” target=”” info=”none” info_place=”top” info_trigger=”hover” info_content=””][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 45px 0px 45px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]“We just don’t have that level of prestige,” says Charles Preston, a CSU student and Black Youth Project 100 organizer who has been working actively along with other students to raise awareness of the impending crisis and put public pressure on the governor to negotiate a budget. Preston, who is majoring in education and African-American studies, has a unique vantage point on this issue—he formerly attended Mizzou, which was rocked by widely-discussed racial justice protests in November. He started at Mizzou, but struggled as a student to cope with the culture; after being pulled over by police on his first night on campus, he went on to have “a horrible experience” in his words. But then “[I] paid off my debt, and came to Chicago State, where I found myself and my passion and really what I wanted to,” says Preston.

“I realize that that moment [at Mizzou] was important, and how difficult it is to organize at a PWI,” says Preston. “But that doesn’t mean that that moment was more important…There’s an immediate urgency. This is one of the biggest issues in Chicago right now and I don’t see that urgency from a lot of people for different reasons. Even the clergy in our community. It’s heartbreaking for me.”

Kelly Harris, a professor of African-American studies, says that CSU’s closing “would really leave the far South Side with basically nothing,” not only institutionally, but in the individual lives of its students. “We serve a population that’s at risk and comes from Chicago Public Schools. A lot of our students are single mothers, parents, and working people who are struggling to keep their head above water.” Chicago State is also a critical resource to its staff, many of whom Harris says are “ex-felons, people coming back from the military, single parents,” and others who would struggle to find other employment.

Harris shares Preston’s perspective on the relative lack of attention to the university’s plight. “[It’s] because Chicago State is in a poor community,” he says. “We don’t have the name of Yale or Mizzou or those other schools. In America, people aren’t concerned about things that happen in distressed areas until after the calamity. New Orleans, Flint….” Harris is worried that the broader public will ignore a poor black community’s calls for assistance until it is too late, allow a preventable disaster to materialize, and then mourn the damage after the fact. And CSU’s predominantly-but-not-historically-black status puts its students in a double bind: they don’t get the attention afforded to black students protesting at elite predominantly-white institutions, nor do they get the rallying cry of history, heritage, and brotherhood/sisterhood they might garner at an HBCU. “People who are from poor areas really are ignored or marginalized by the larger public,” Harris says. “We have to tell our story, let people know what we’re doing.”

Paris Griffin, the president of the university’s student government, is one of the students trying to do just that. Griffin, like Preston, is a transfer student. She began her college career at Southern Illinois University, but once she was expecting a child, she came home to Chicago to be closer to a network of support. The “very family-like atmosphere” at CSU allows her to be successful as a student while being successful as a mother, she says. “I’ve had access to opportunities that I didn’t have anywhere else.” Griffin received a scholarship to attend CSU, and this summer has an internship with Apple. “My experience has been really crazy,” she says. “It’s really flexible… if there are days I need to bring my daughter to campus, there are people that I trust. I don’t think I would have been able to thrive with my current situation anywhere else.” Affordable tuition, childcare, and flexible class times have made it easier for her to pursue her degree, while also participating in campus activities and living a full life as a student.

If the university closes, or if students are unable to continue attending because they are not receiving state aid, Griffin says “it’s going to take a lot of opportunities away from people who are trying to become independent of the systems that are holding us.”[/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 45px 0px 45px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”#bababa” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_blockquote cite=”Kelly Harris” type=”left”]We have to tell our story, let people know what we’re doing[/x_blockquote][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 45px 0px 45px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]Preston sees himself as an example of someone trying to get free through his time at CSU and the resources it provides. “The school saved my life.” Preston recounts a crisis when he was diagnosed with severe depression and suicidal ideation and hospitalized for three days. “But how I got to that point, to even get care, was to get to CSU. From CSU’s counseling services, they got me the help that they could give me. It was a resource that was there for someone that can’t afford a psychiatrist.”

In his view, these stories are typical. “[There are] stories about black people with trauma in the community that come to CSU. I worked with someone that used to do armed robberies—just robbing people with a gun. That was his income. One nursing student came to our town hall saying she was a drug abuser and she turned her life around. This campus saves the lives of marginalized people. To them [the governor and his supporters], it’s a numbers thing. But to me, it’s a human thing.”

Preston characterized the threat to CSU as a form of state violence. Griffin calls it “being held hostage in a political chess game.” But the issues involved in the CSU crisis go beyond the structural racism of budget cuts and negligence. In response to a wave of student and community protests, a high-ranking staffer in Governor Rauner’s office circulated a memo criticizing CSU for previous administrations’ financial mismanagement—and for black graduation rates:

While 83% of white CSU students graduate in six years, only 19% of African-American students and 15% of Latino students do the same. On average across Illinois public universities, white students have a 61% graduation rate while African Americans have a 39% graduation rate. In Illinois, Chicago State has the second lowest graduation rate for African-American students (behind NEIU’s 8% graduation rate) and the second highest graduation rate for white students (behind UIUC’s 87% graduation rate).

In an early contender for Best Clapback of 2016 year-end lists, CSU president Thomas Calhoun wrote a lengthy open letter response, in which he (politely) called these numbers bogus—largely because they did not encompass transfer students, who make up two-thirds of CSU’s student body.

For example, the graduation rate for full-time transfer students in the 2008 cohort referenced in Mr. Goldberg’s memo is 51%. That graduation rate, however, is not reported by the federal system…. It is implied in your memo that CSU is graduating white students at 83%, a much higher number than students of color. This misleading statistic fails to recognize that within the 2008 cohort referenced, six white students began their degree, and five completed.

Yes. Five. But beyond the misleading use of statistics in Rauner’s office, what’s more troubling is this: as all of Illinois’s public universities face budget challenges that have prompted their leadership to protest vocally, the governor’s office singled out only the majority-black school and attempted to justify its potential closure using graduation rates in the midst of a dispute that is supposed to be about money. It’s a dog whistle familiar to anyone who has observed school policy in Chicago, Philadelphia, or Detroit—Rauner is invoking the narrative of the “failing black school,” an institution so sullied by its failing black students and their low numbers—test scores, graduation rates—that we would all be better off if it didn’t exist.

In 2013, that rhetoric stripped the city of 50 elementary schools, serving 88% black children. In 2015, it almost made Walter H. Dyett High School a relic of the past. If we want to see Chicago State University survive another year of serving those most in need of a chance at a college degree, it’s going to take everyone’s voice to keep it thriving. As far as Griffin is concerned, the threat to the university represents more than a threat to her individual situation. The school, she says, is “a community that is conceived to build each other up. It’s always been a beacon of light… it’s always been an inspiration, to know that you can be right in the middle of what is deemed as the hood and still be able to succeed.” For the Roseland community and many black Chicagoans across the city, preserving that beam of light may be a matter of life and death. [/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section]