The noose was fitted from birth.

This one, the power cord of an air conditioning unit. Plastic and wires replaced the hard hemp knot, but the end result still the same. A dead Black body; a spirit extinguished. At once a tethering and an untethering, a joining of a broken man with his broken body. This instance, the tying hands were his own, but the noose had been fitted from birth. They’d given him a rope and a tree and set a fire under his feet and told him to jump or die. And he chose to jump rather than be consumed by the flames.

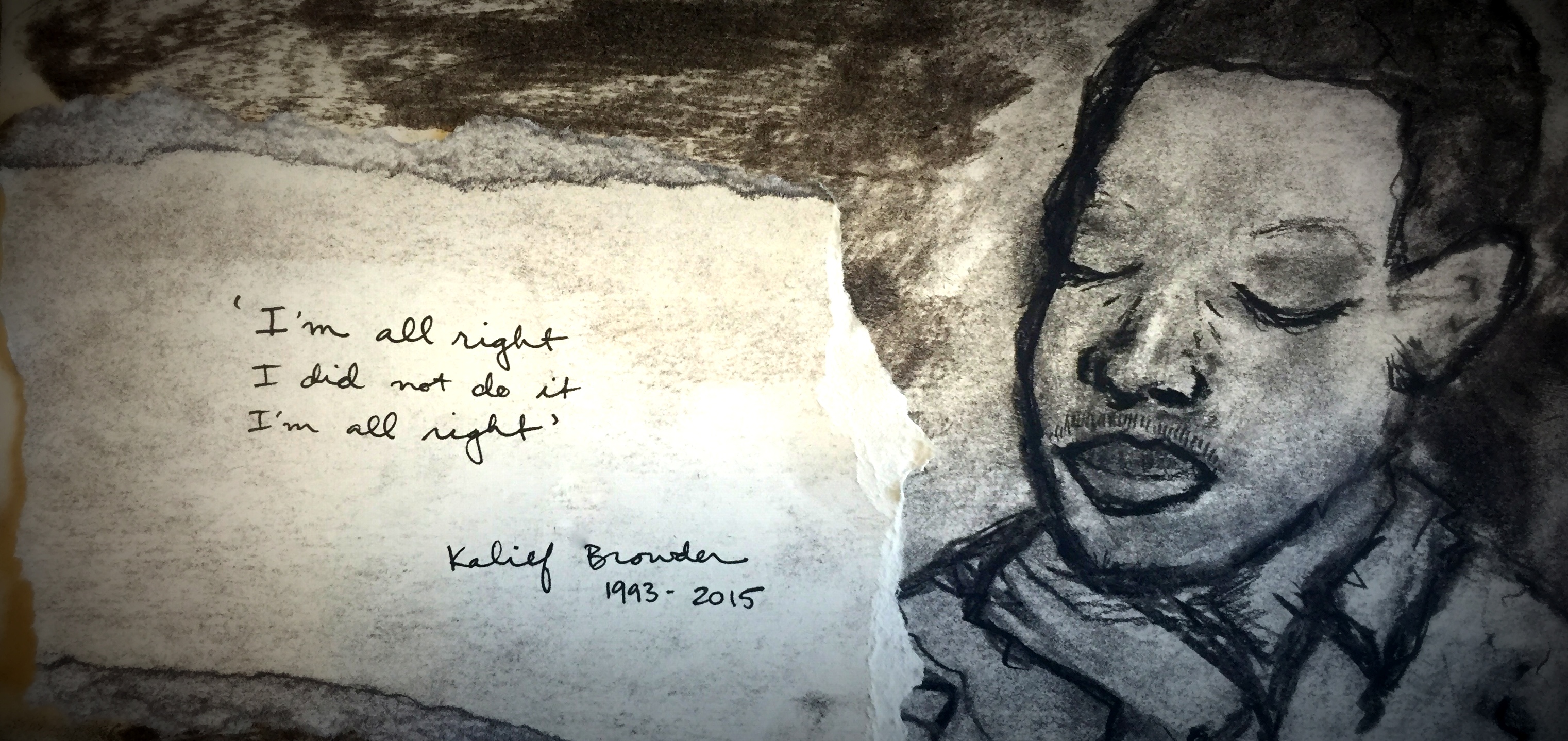

Kalief Browder’s death wasn’t a suicide.

Two years in solitary confinement will destroy any man. It will crumble the soul from the outside in, until all that’s left is the raw nerve of pain. A cruel, but all-too-usual punishment, in an all-too-usually cruel system. An instrument of torture in a corrupt and topsy-turvy world of torture, a world where prison beds are projected and reserved for Black boys and girls at the first sign of distress. It is a system of punishment, designed with the end goal of brutal efficiency: of creating prisons out of the fabrics of our own lives.

Mr. Browder entered that torture chamber at 16, the age when white peers are given the most precious luxuries of chances to fail, learn, and grow. Sent to Rikers, an island of pain operating in spite of numerous documented violations of the basic tenets of humanity, he spent three years enduring recorded beatings by guards and inmates, long periods of solitary confinement, and failed suicide attempts. His stay had been extended simply because his family could not afford bail.

The charge that sent him to that bastion of brutality? An alleged theft of a backpack.

That charge was dropped.

Two years after Browder was finally released from Rikers, he completed the deed that he’d tried before in prison. So ended five years of unspeakable pain, inflicted by the hands of a thoroughly corrupt, brutal, and inadequate policing, prosecution, and prison complex that manages to somehow still be referred to as the American Justice System–without irony. That system killed him. That system gave him his noose and told him to jump. It ruined a child. It ruined a family and a community. It added his name to the litany of names of Black girls and boys and women and men that we recite like names from a prayer book as we march and cry out. That list has become our own perverse Deuteronomy, a canon of the numbers of those crushed under the boot heel of white supremacy. His name and the names on that list are America’s blood debt, as is the red stain on the conscience of all of us who watched but did not cry out.

The phrase we use now, still endeavoring to convince the world of our humanity, is “Stop Killing Us.” This is adequate to a point. The phrase invokes the thousands (502 at the time of this writing), who die yearly, directly at the hands of violent police. But does it fully evoke images of the thousands and thousands more who are beaten and harassed by those police, of the millions more who fear for their lives every time they see blue lights, of those languishing behind bars for lifetimes for using marijuana, of the innocents in prison now being stripped of their humanity? Does it capture those who can no longer bear the pain of this world and choose to end their time here–a population represented by skyrocketing suicide rates among Black youth? Does it impress upon the powers and principalities the psychological damage that teenagers in a Texas suburb must face now that they truly realize that there is no one to call to protect them from the police?

The fact of the matter is that there is not one of us in America’s Black permanent underclass that is not damaged or won’t become so in due time, not one of us that will live a full life without the scars of brutality. Our cry is to “Stop Killing Us,” yes, but death comes not only to the body. To stop simultaneous cultural degradation and exile. To stop marginalizing us to the polluted edges of cities. To stop pulling the safety nets out from under us. To stop using the police as mercenary occupying forces in our neighborhood, to stop replacing every single social service occupation with patrolmen. To stop imprisoning us, to stop beating and bullying us. To stop shooting us with our hands up. To stop fashioning our nooses before we are even given our names.

Kalief Browder’s death was not a suicide. It was a critical failure of humanity. We owed him then, and we owe him now, only now the debt can never be repaid.

He was twenty-two.

Comments

“That list has become our own perverse Deuteronomy….” Powerful. Thank you.