Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto. “I am a human being, I consider nothing that is human alien to me.” - Terence

When the Eagles lost the Super Bowl in 2005, I didn’t care. I wasn’t interested in sports, I didn’t watch the games and it wasn’t a part of my life. The opposite was true for my stepfather, and I remember an uncomfortably quiet Monday morning following the loss. I figured I’d poke fun at his team’s defeat and made my way to my parent’s bedroom chanting, “Haha, the Eagles lost, haha!” I was swiftly met at the door by my mother, who grabbed my arm and yanked me down the hallway, out of earshot. “Shut the fuck up,” she hissed. “Right now isn’t the time.” My feelings were hurt, of course, but that’s slightly beside the point. What’s worth noting here is that something was off-limits. There was this thing in which my stepfather had a strong investment, though for the life of me, I couldn’t understand why it was such a big deal. Surely, his graven images had been condemned to the flame.

The quickest way to piss off any ardent sports fan is to say, “Well, it’s just a game.” Because it isn’t. It represents shared joys and disappointments, dozens of impassioned defenses, and, in some cases, a lifetime’s worth of memories, which, while perhaps being somewhat distinct from the game itself, are inextricably linked for the fans. We live in a country where it is particularly true that sports are the object of the collective passion. Though you are in the stands, at the bar, or in your living room, you have entrusted your heart to the field. A time, a place, a feeling. Something to hope for. Someone to be.

No longer a child, I now understand this. Indeed, as a black man living in an America seemingly as determined now to deny the humanity of black people as it was in 2005 – as it has always been – I understand that football was not my stepfather’s petty distraction. It was both escape and affirmation. Escape from the excruciating tedium of making one’s living while endeavoring to find self-worth and meaning in a society in which one is violently and irredeemably othered. To affirm possession of the very best virtues which are the heritage of all humanity, without exception: the will to overcome adversity, and the vision and creative power necessary to compel reality to mirror our dreams. This is, fundamentally, a humanism.

My stepfather and I have made unto ourselves somewhat different graven images.

Last December I tried, unsuccessfully, to write an analysis of the one-year anniversary of Beyoncé’s Visual Album. The chief reason I didn’t finish the piece was because, to my mind, any fair analysis could be likened to a critique. Critiques require disinterest, dispassion—cold, hard, application of standards. I can pretend to none of those things when it comes to Beyoncé. Can any man critique his idols? I should think not; or, at least, not effectively. There’s a sense in which he can only revere them. I revere that woman. I am not disinterested. I am not dispassionate.

Notwithstanding, I have spent a lot of time trying to organize my thoughts around what exactly makes Beyoncé paramount. Not commercially, and not in the artistic merits of her work (some defensible arguments could be made considering those things alone, I suppose), but in the hearts and minds of her militant fandom. After all that thinking, my considered opinion is this: it’s a form of humanism. Let me explain…

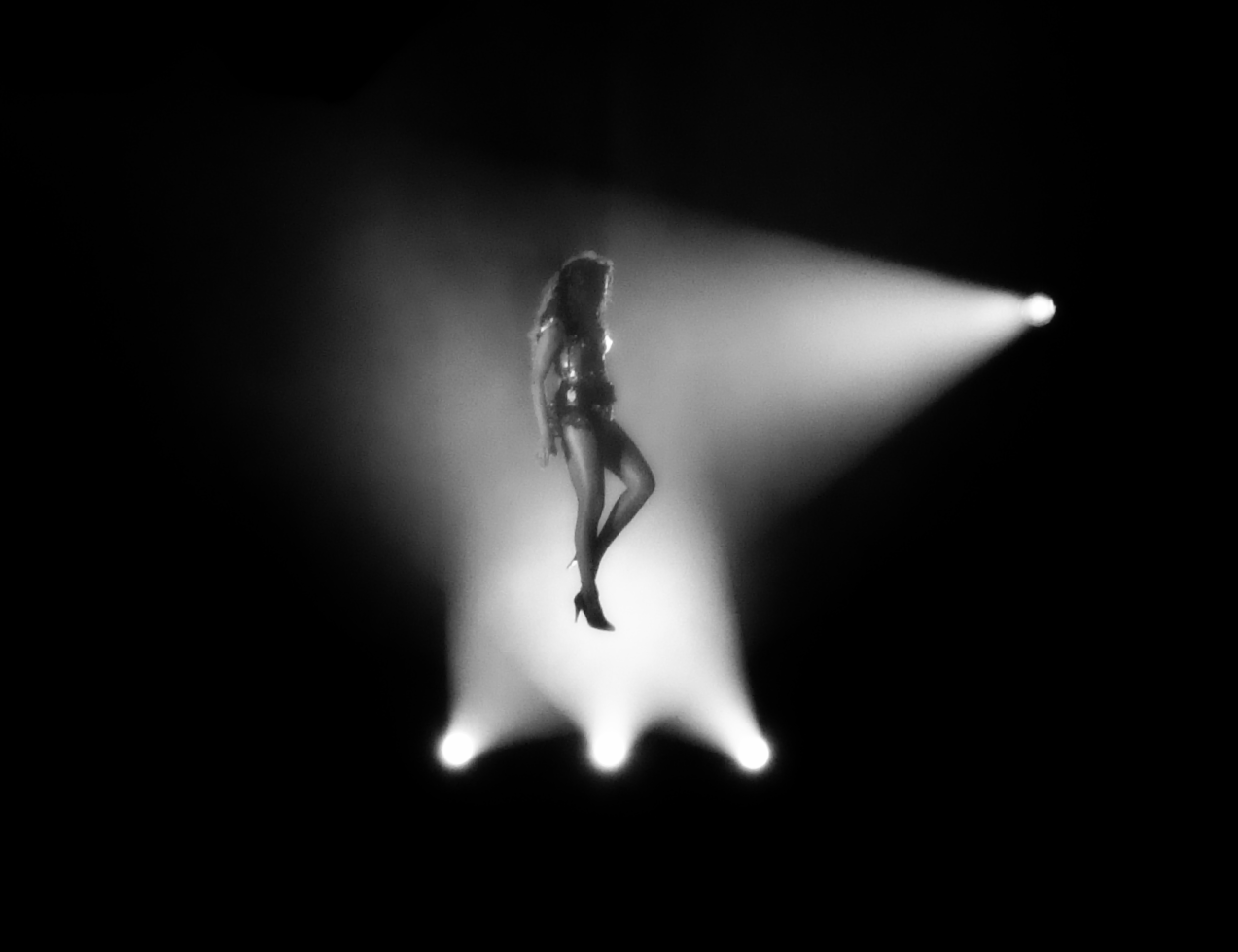

In 2007, I visited my uncle’s home in Maryland. He had a pretty comprehensive cable package, the kind with various music video-only channels. Beyoncé had just released a video anthology and a deluxe edition of “B-Day”, and MTV Jams was playing previously unreleased videos from the album. I was absolutely enthralled. On “Suga Mama” she is so androgynous, yet visually dictates the force of her own femininity, suggestively riding a mechanical bull while singing about being a grown man’s financial sponsor in exchange for sexual gratification. On “Green Light” she’s crawling between the legs of six or so women and simultaneously slithering over the sound of those horns like a serpent. Something about the way she’s in control of every motion of her body, every facial expression, is almost bizarre in its perfection. The camera loves her and she doesn’t care — it is an unrequited passion. She is the very image of a woman, a human being, in complete possession of herself. Do people such as this exist in the world?

When my uncle came down the stairs, I hurriedly changed the channel before he could observe what I was watching. I didn’t want him to ask me any probing shit like, “Who’s this? Beyoncé? She’s sexy, huh?” I didn’t want to have to pretend to be experiencing this art in a way I wasn’t. I was 15, closeted, and to my mind, did not reserve the privilege to be vocal or outwardly passionate about the things that inspired me. That meant pretending to be a merely casual Beyoncé fan in the same way I pretended to like girls.

Simply stated, Beyoncé became The Vessel. I watched America deify The Vessel for so many of my hopes and dreams. I watched her carve out another stratosphere – one in which she was above competing with anyone but herself. But what I find incontrovertibly humanistic about Beyoncé and her career trajectory is that watching her, you are under no delusions that you will ever be able to do that. What it makes you feel is a desire to cultivate the thing you’re meant to be doing as forcefully and beautifully as she has. To find something more important than pain or exhaustion. To see beyond and to create to the fullest extent of your abilities. I would compare this sensation to watching an athlete play exceptionally well in any given matchup. You know you’ll never be able to do that, but you’ve invested in that…and it feels like power. You carry it with you long after it has ended.

There is a larger issue of cultural legitimacy, here. However annoying or unreasonable, it’s generally acceptable for my stepfather to root hard for the Eagles – to share in the joys of victory and the sting of defeat – in a way that it’s probably not for me to care so much about Beyoncé. After all, what kind of culture or media mostly consumed by women and gay men could be that important? I’m aware of this distinction, but I am also aware of its arbitrariness; that it is, in truth, a distinction without difference.

So many things influence what kinds of popular culture we gravitate towards. Race, sexuality, gender, religion, political commitment. But what remains essentially the same is the investment. That this thing will be a part of my life in a way that is somewhat difficult to articulate. I’ll root for it. I’ll see myself in it. It will color parts of my life that it is ostensibly unrelated to. That’s Beyoncé for me and I’m inclined to believe – or at least, I’m hopeful – that we’re moving toward a space where that’s okay. To me, that’s a form of humanism. As if by magic, the line between who we are and the culture we consume and create becomes increasingly blurred. To employ a clichéd maxim, art imitates life. Or vice versa. Or whatever you’ll abide. Popular culture is, in many respects, vicarious.

—

The summer after graduating high school was a precarious one, in the sense that but for some act of providence, I might not have lived to see it. That April, I’d come out to my mother, confessed my love for someone for the first time, and attempted suicide – in that exact order. Looking back, it was a time of such promise. I was standing, however shakily, in my truth. I’d gotten accepted into my first choice of schools with a considerable scholarship, and here everyone was telling me that it would get better. I didn’t believe them. When you live for 18 years with the belief that there is a fundamentally unlovable part of you and that this burden is also something no power in heaven or on earth can relieve you of, you learn to exist by obfuscating. Simply put, I didn’t know how to be.

It was perhaps for the first time that I realized how angry I was about all of this when, in the car with my best friend on I-95, “Survivor” came on the radio. We’ve all likely experienced the sensation of hearing childhood songs as adults and finally finding meaning in them. In that moment, “Survivor” wasn’t about all the people I harbored resentments toward, some of whom I loved. It wasn’t triumphant. It was ruthlessly hostile. It was aimed at the voices in my head that were threatening to end me. It was aimed at Death, who’d had his hand on my shoulder since I’d learned that there was no difference between being gay and being the worst kind of wicked, concluding that the only good thing I could ever do would be to allow him to embrace me.

I slumped my head against the window, pretended to sleep so that I could compose myself and cried the angriest tears I can recall. I’d like to believe that in that moment I resolved within myself that I would live – fully and well – just to spite them. I had not been touched, I had not been ended, and I was not dead. Thought that I would self-destruct, but I’m still here. Even in my years to come, I’m still gon’ be here.

“If you survived a breakup…If you survived an illness…If you survived sexism…If you survived racism…If you survived a death in your family…If you survived a bunch of haters…I want you to put your fist up like this and celebrate with us, tonight!” – Beyoncé, performing live in Los Angeles, 2007.

Back then, Beyoncé was my idol, so if you’d asked me I might have told you that her strength guided me through that moment. Now that she’s also my hero, I know that it is partly because she has known her strength that I have known my own. That because she has honored the best in herself by seeking it out ceaselessly, I have learned – I am learning – to do the same.

Hero worship is often seen as something pejorative. I do not dispute that there are certain cases in which it is deserving of that perception, but if by this we mean finding someone who shows us how to be, I should think it unavoidable. Beyoncé has shown the world how to be. We are sometimes fated to make gods of those whose magic we do not believe we possess. We believe this in error, as Juan Mascaró, in quoting the Upanishads, says, “that God must not be sought as something far away, separate from us, but rather as the very inmost of us, as the Self in us above the limitations of our little self. In rising to the best in us we rise to the Self in us, to Brahman, to God himself.” Let us worship our heroes, sure in the knowledge we are praying to that which is already within.

—

Beyoncé is undoubtedly the culmination of the legacies of her predecessors – Tina, Michael, Whitney, Janet – but she is also best viewed as an almost entirely separate phenomenon. The institution of American celebrity is such that it is only satisfied to place someone atop the highest possible summit so that it can push them off. It is a formidably destructive power, capable of immortalizing the subject while ultimately and irreparably dehumanizing them. Indeed, it has maimed and destroyed those who came before Beyoncé. That this black woman has seized this threat and turned it into something majestically life-affirming is absolutely remarkable. That this black woman belongs to the mad days of my youth fills me with pride beyond measure.

There’s a sense in which Beyoncé as we know her could not have survived if she didn’t dare to be perfect. In an industry where sex sells, she had to portray an appeal that was so manicured, it might be said to be undesirable. In a society where black female sexuality is so regulated and scorned, she quested on a tightrope. Beyoncé had to teeter between giving it all away and leaving it all to the imagination. Sexy, but never sexual; the latter implying agency.

White pop stars with comparable commercial sales could afford to be lax in their presentations in a way she could not. Beyoncé had to give you everything. Whereas perfection was something that could be faked for others, it was the essential mandate of Beyoncé’s career. If this were untrue, there would be no Beyoncé. She herself has confessed how creatively stifling and oppressive all of this became, how difficult it was.

The massive effort required for Beyoncé to become and remain Beyoncé contributed to this notion of near-divinity. There is, after all, a reason her fandom is cult-like. But the weakness of divinity is that gods can only ever be feared, worshiped, venerated. They can never be truly loved, for love is a human endeavor.

Friday, December 13, 2013 would change all of that. What is important about this date? That by its stealthy production and guerrilla-ambush-assault-release, the Visual Album forever changed content distribution models? That it would garner Beyoncé the highest first week sales of her career? No. What interested me was the idea that by conceiving this piece at all, Beyoncé did violence to the very flawless facade she’d projected to catapult herself to this rarefied space in the first place.

I will never forget the initial shock and awe of hearing Beyoncé sing about doing unprintable things in the back of a car. I will never forget the thrill of Beyoncé defiantly and triumphantly telling the world, “Dis my shit! Bow down, bitches!” It is beyond question that she had earned the right to say it, but witnessing her do so felt like the fulfillment of a manifest – if somewhat elusive – telos.

To witness her vulnerability in tracks like “Jealous” and “Mine”. To experience the sexual baptism that was “Rocket”: Your love feels like all four seasons growing inside me, life has a reason. To observe the subtle politic of “Superpower”: The laws of the world tell us what goes sky and what falls; it’s a superpower. The laws of the world never stopped us once, ‘cause together we got plenty superpower. Here was someone who, for me, occupied that space of wonder which constitutes one’s childhood, one’s youth, while putting aside all childish things.

It was 2013 – 10 years since the launch of her solo career – and Beyoncé had decided a few things: that after a decade of setting the world on fire and claiming a cultural territory theretofore unmatched in its scope, she would do more than entertain us; that her music – indeed, her very place in the American pop cultural pantheon – was political; that she belonged to herself; and that she would not be content simply to fill arenas and sell records. Beyoncé wanted to be human.

—

The Visual Album was the crowning moment of what had been a truly transformative year for me. I’d spent the previous 11 months confronting so much of what I’d hitherto been afraid of about myself. I accepted things that 15 year-old Robert, mesmerized by those Beyoncé videos, would have found, frankly, impossibly arrogant: I’m a good person. I’m not sick. I’m not dirty. I’m not wrong. I love. I am loved. I had chosen life, and not life generally, but my own life – every part of it. Amor fati.

You will forgive me if, like my stepfather and the Eagles, I see her and this pop cultural moment as impossible to divorce from my subjective experience. That, my friend, is the point. Are any of these things solely because of Beyoncé? Assuredly not. The question then becomes: Would my experience be the same without Beyoncé? Assuredly not. She is a time, a place, a feeling. Something to hope for. Someone to be. Beyoncé is a humanism.

“It took a while, now I understand just where I’m goin’. I know the world and I know who I am, s’bout time I show it.”

Comments

Beautiful.

Amazing piece! Being human and living through what makes us happy, be it sports, music, or a music artist– that is definitely a beautiful form of humanism. Every form should be celebrated.