The new Brooklyn is different. It’s a place people come to, not a place people come from

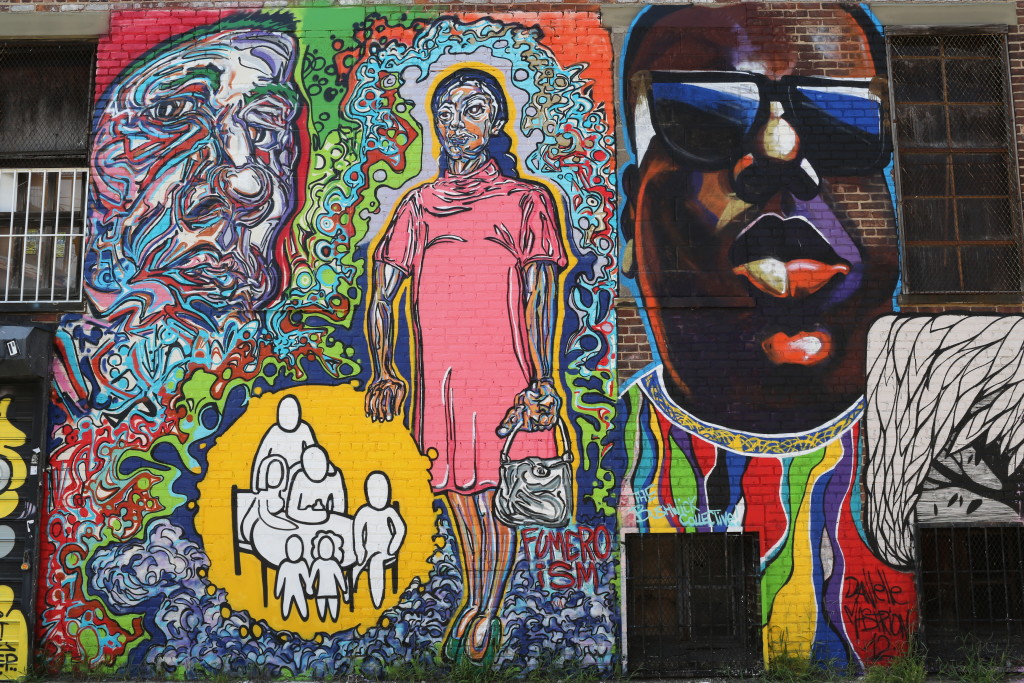

Photo by Chris Ford

[nextpage title=”Next Page”]

The image of modern-day Brooklyn is often viewed as a haven for hipsters and the middle and upper middle class, with boutique shops, gyms, a giant arena, cafes, and structured parks. Brooklyn has become a face of gentrification in the U.S., but despite its vast economic growth and seemingly integrated neighborhoods, its history as a diverse hub for immigrants, African-Americans, and Latinos has not yet been forgotten.((DeSena, J. 2012. The world in Brooklyn: Gentrification, immigration, and ethnic politics in a global city. Lanham: Lexington Books.)) The original characteristics of the borough were produced from struggle, hard work, and the hope for a better life in the heart of the city.

‘Culture’ and ‘character’ are important, yet difficult-to-define concepts related deeply to gentrification. One major component of urban culture, and especially in New York City and Brooklyn, is hip-hop music. Rap music has been known for its ability to provide insight into the socioeconomic conditions of blacks and Latinos in the U.S. Born from the streets of the Bronx, hip-hop is deeply-rooted in the streets of urban centers. Scholar and cultural critic Tricia Rose states, “Rap music, more than any other contemporary form of black cultural expression, articulates the chasm between black urban lived experience and dominant, ‘legitimate’ ideologies regarding equal opportunity and racial inequality.”((Rose, T. 1994. Black noise: Rap music and black culture in contemporary America. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.))

Live from Bedford-Stuyvesant, the livest one. Representing BK to the fullest

Brooklyn, especially, is home to some of the most notorious MCs, who hold tight to their hometowns, representing and paying homage to the borough and its various neighborhoods in song. Artists like Jay-Z and Notorious B.I.G. gave audiences an explicit look into the daily life and culture in Brooklyn’s streets. Gentrification((Just what exactly is gentrification? Here it is the process of renewing and renovating neighborhoods in cities that were segregated and largely occupied by minority groups. This process takes urban areas that were isolated and considered slums or ghettoes and redevelops them into desirable city landmarks that attract mostly high-income residents. The process generally starts with sales of large plots of real estate and redevelopment of low-end to high-end real estate, expensive recreation, and a variety of private business.)) is at odds with the concepts of authenticity and history embedded in the roots of hip-hop, and Brooklyn appears far different than the lyrics heard in “Brooklyn” by Mos Def or the visual image portrayed in films like Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing.” The familiar faces of the working class and the comfort of local businesses have been driven out by the increase in property value, and Brooklyn’s founding culture has gone along with them. Through song lyrics, historical events, and opinions from rappers themselves, explaining the relationship between hip-hop and gentrification is made clear, and unveils how gentrification continues to damage the culture of hip-hop’s Mecca.

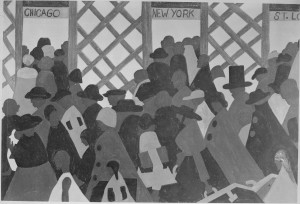

When Blacks journeyed to the North as a part of the Great Migration((For a good resource on this, check out The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson)), they experienced intense segregation in the housing market. Racism remained rampant in the U.S. and as cities grew, property owners made attempts to keep Blacks out of certain neighborhoods by raising rent, redlining, and flat-out closing off housing markets. Though Harlem was the initial destination, the Ellis Island for Black Americans who migrated to New York City in the early 20th century, the creation of the A train subway from Harlem to Brooklyn in 1936 encouraged black people and new immigrants to flee to cheaper housing and better job opportunities. This development also shifted a great portion of New York City’s economy to Brooklyn. During this time Brooklyn’s industry (based mostly in trade from ports) was doing well and the cost of living was incredibly cheap in comparison to Manhattan, which encouraged many black and Latino immigrants to settle.

When Blacks journeyed to the North as a part of the Great Migration((For a good resource on this, check out The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson)), they experienced intense segregation in the housing market. Racism remained rampant in the U.S. and as cities grew, property owners made attempts to keep Blacks out of certain neighborhoods by raising rent, redlining, and flat-out closing off housing markets. Though Harlem was the initial destination, the Ellis Island for Black Americans who migrated to New York City in the early 20th century, the creation of the A train subway from Harlem to Brooklyn in 1936 encouraged black people and new immigrants to flee to cheaper housing and better job opportunities. This development also shifted a great portion of New York City’s economy to Brooklyn. During this time Brooklyn’s industry (based mostly in trade from ports) was doing well and the cost of living was incredibly cheap in comparison to Manhattan, which encouraged many black and Latino immigrants to settle.

The borough was economically stable during this time, which accommodated a relatively diverse socioeconomic population. However, in the early to mid 1950s, Brooklyn’s industry began to decline, and ”white flight” mirroring white suburban migrations in the rest of America changed the landscape. The residents who could not afford to move remained and were forced to navigate a new landscape. This occurrence resulted in lower property values, cheap rent prices, and the loss of big business. Though some Brooklyn neighborhoods maintained their middle-class population (such as Brooklyn Heights) most suffered severe economic loss.

Hip-hop was born in the streets of the Bronx, around the same time as the major demographic shifts in Brooklyn. In the mid 1950s, urban planner Robert Mosley developed the Cross Bronx Expressway (CBE); a six-lane highway that cut through several Bronx neighborhoods, displacing 60,000 people and resulting in the loss of nearly 600,000 jobs. “Few roads in America have histories as tortured as the Cross Bronx Expressway. The master builder Robert Moses gouged the highway through crowded neighborhoods, displacing tens of thousands of people and, critics say, helping set the stage for the arson and crime that ravaged the borough for a generation.” This itself is an early example of development-based displacement common to gentrification. However, the turmoil created by the development of the CBE sparked inspiration in young people to find solitude amidst despair. In the early 1970s, hip-hop emerged from the depths of this chaos.

Bronx natives (many of whom were West-Indian immigrants) used lampposts to plug in their sound systems and experiment with turntables. Clive Campbell, commonly known as DJ Kool Herc, was the first of many popular hip-hop DJs to test sounds and energize the Bronx at public gatherings during the nascence of hip-hop. “Working two turntables, he switched between duplicate vinyl to keep the instrumental breaks playing and the dancing going indefinitely, and break dancers, shout-outs, MCs, and DJ rivalries all became part of the Kool Herc legacy.”((Jeff Chang. 2005. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation)) The popularity of hip-hop gained momentum as it began to spread throughout the borough. Hip-hop’s beginnings started off as a community art form. It was a way in which local neighborhoods could come together and relieve themselves of the pressure of daily life.

You crazy, think your little bit of rhymes can play me? I’m from Marcy, I’m varsity, chump, you JV

The rising popularity of hip-hop in the Bronx sparked city-wide fascination. Utilizing public space and supported by their neighbors, MCs and DJs began popping up throughout the city, including Brooklyn. The genre took on a certain admiration and style in Brooklyn as it quickly produced some of the most infamous MCs.

The 1980s and 90s were an especially important time for Brooklyn hip-hop, as artists like Big Daddy Kane, Mos Def, Talib Kweli, Notorious B.I.G. and MC Lyte emerged and became prominent figures in the genre. These artists dedicated lines and even whole songs to the streets of Brooklyn, giving credit to the neighborhoods that brought them up and provided imagery to outsiders of what life in Bed-Stuy or Fort Greene might look like. In the 1984 single, “Do Or Die, Bed-Stuy,” the MCs of Divine Sounds used their song title to signify the neighborhood that, throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, experienced extreme violence. The phrase, “Do or Die, Bed-Stuy” became a popular reference to the Bedford-Stuyvensant neighborhood known for brawls, gang violence, and its largely black and Latino immigrant population; a strong juxtaposition to today’s brownstones and million-dollar real estate. These descriptions of everyday life in Brooklyn were common themes in artists’ music, as their upbringing created inspiration for their personal narratives.

While Brooklyn had a great deal of issues with crime and poverty, hip-hop provided a platform for artists to discuss the problems their neighborhoods and families faced on a larger scale. Mainstream music and the rising popularity of hip-hop allowed for these important discussions about race and class to be broadcast. For example, the Brownesville neighborhood in East New York had a reputation for delinquency. In songs like “Welcome to Brownesville” rap duo, M.O.P publicized their experience living in the crime-ridden Brooklyn neighborhood. These lyrics were important for the outside world to hear, not for criminalizing blacks, but in shedding light on problems that plagued urban communities. But was the message received? The instinct now seems to be to remove the negative images that native rappers like M.O.P discussed in their music—by removing the people afflicted by them.

Gentrification is a system that transforms the disposition of an urban space, generally towards one of white-dominated middle or upper-class-ness. Sharon Zukin, an urban sociologist, describes gentrification in a similar manner stating, “the conversion of socially marginal and working class areas of the central city to middle [and elite] residential use.”((Zukin, S. 2010. Naked city the death and life of authentic urban places. Oxford: Oxford University Press.)) Gentrification affects numerous aspects of a neighborhood, some that are easily repaired and some that are not. Rent prices rise significantly as the value of living in gentrified neighborhoods increase, driving out low-income residents who can no longer afford the cost of living. Brooklyn has a unique energy that is heavily inspired by art and multiculturalism. However, gentrification uproots the minorities, artists, local business owners and groups of people that contributed to the making of an authentic urban space and community.

Hip-hop is an integral part of urban culture and an indicator of the changes in it, including gentrification. This change in community disposition when outwardly disregarding a neighborhood’s current residents is harmful. Sensitivity to a city or neighborhood’s culture is important to its history and future, and hip-hop music is a large contributor to Brooklyn’s organic spirit. And if there’s one thing that is very clear about hip-hop, origin and history, where you’re from, they matter.

There are several ways to describe gentrification, both positive and negative. It can be seen as an economic stimulant, revitalizing neighborhoods that were once run down or deemed “ghetto,” breathing life into dilapidated urban spaces. On the other hand, gentrification is often also a mechanism used to rid urban neighborhoods of low-income residents and wipe out long-standing communities. The complexity of gentrification cannot be reduced to either of these descriptions, but its impact on the culture of urban neighborhoods stands as one of its most potent effects. Gentrification has been an ongoing process throughout the history of urban spaces, yet certain boroughs in New York City, and in particular Brooklyn, have seen particularly intense rounds of gentrification in the last decade or so. Brooklyn’s local culture, including one of its cornerstones, hip-hop, has undergone sweeping changes. Hip-hop and regional identity have a long-term relationship, as most artists have always been quick to claim their hometown — Brooklyn is no exception.

Dr. Stacey Sutton, Assistant Professor of Urban Planning at Columbia, explains the relationship between race and gentrification stating, “People say cities always change, they’re dynamic. Absolutely. But the question for gentrification and the problem . . .is the degree to which these changes continuously disadvantage the same groups of people. There were people, predominantly black and Latino people, that were relegated to the city when we saw white flight and suburbanization, and the city was demonized overall. Over time, the city has become increasingly desirable, so as people move back to the city the question is a more fundamental, ethical question. Should people with more capital be able to locate in areas as they see as more desirable although those areas are already being occupied or have been occupied by groups that have been marginalized?”

By juxtaposing images of Brooklyn from a Biggie song up against images of Brooklyn today, the demographic difference from then to now is made painfully obvious. “The new Brooklyn is different. It’s a place people come to, not a place people come from, and where residents don’t have a traditional, urban village way of life but are very proud of the ‘authenticity’ of the neighborhood where they chose to live.”((Zukin, S. 2010. Naked city the death and life of authentic urban places. Oxford: Oxford University Press.))

When gentrification meets with a long-standing urban structure like hip-hop, there necessarily comes with it a great deal of change; from the refurbishment of the neighborhoods and street corners where Brooklyn rappers grew up, to the transformation of styles and sounds people associate with their music. One example is the friction over the creation of the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, a project in which fellow rapper and Brooklyn native Jay Z played a huge role. Rapper Mos Def expressed his concerns over the development of the Barclays Center in a poem titled “On.center.stadium.status”:

“It’s simplerto kill/A stranger/Than it is/To slay/A/Neighbor/DECREE!/HAIL THE NO NATION BEAST!!/whose shadow alone/buries homes/And swallows streets/Pass gas then/Pick its teeth…”

In an interview with Vulture, Mos Def expounded. “My concern is, none of those people who built that stadium know what it’s like to grow up in the projects. And the people in the neighborhood don’t yet benefit from the stadium’s presence in the community. I would love for Barclays and the NBA and whoever else to prove me wrong, by engaging in the community, not just on some [surface] level for the photo op. But to really be concerned with enriching the lives of people in that community.”

Hip-hop culture was bred from the streets of the Bronx, but has played an instrumental role in global culture; inspiring artists, fans, and subgenres across the world. The Golden Age of the late 80s and early 90s was filled with distinct beats, varying soul and jazz samples, West Indian-inspired sounds and renowned DJs and MCs, spawning a larger cultural wave that spread widely. Brooklyn rappers at the fore of mainstream hip-hop were key contributors to this era. Brooklyn’s sound was most known for its dark and gritty beats, with samples from various genres, from jazz to country and rock n’ roll. The drop of a drum loop is synonymous with golden age hip-hop, a beat so distinguishable that today’s generation of hip-hop listeners could easily associate the sound with the era; the hallmarks were songs like the 1992 single, “Who Got The Props?” by Black Moon or the 1994 single “Crooklyn” by the Crooklyn Dodgers. Smif-N-Wessun’s “Sound Bwoy Bureill” and Notorious B.I.G.’s “Respect” were examples of the West Indian influence in Brooklyn hip-hop.[/nextpage]

[nextpage title=”Next Page”]

But every golden age has its end. The end of the ‘90s saw a precipitous decline in the notoriety of Brooklyn hip-hop. Jay Z still went platinum steadily, but outside of him few popular rappers were claiming Brooklyn as their home. Many of the borough’s well-known artists stopped making music, and music from other regions, like Outkast’s Atlanta, took the creative reins of hip-hop. The Notorious B.I.G. was murdered in 1997. The beloved hip-hop duo Black Star (Mos Def and Talib Kweli) never made another album together after their 1998 hit album, although they would each make successful solo albums in 1999 and 2000, respectively. MC Lyte released her last album in 2003, two years after Foxy Brown’s last in 2001. Biz Markie’s last album was in 2003. Rather quickly, Brooklyn-based hip-hop seemed to be falling out of favor in mainstream hip-hop circles.

Gentrification began killing one of hip-hop’s most vibrant and formative eras, the bedrock of modern rap, as it also uprooted the bedrock of the borough. It effectively dismantled a borough by taking those very people who were immersed in hip-hop culture, and displacing them, destroying the culture they managed to build from scraps. There’s the famous Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood and Jay Z’s home in the Marcy Housing projects. One of his more recent mentions was in his song, “Empire State of Mind” featuring Alicia Keys, in which he shouts out 560 State Street in the Boerum Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn. In 2012, he surprised a young Jewish couple who now reside in his old apartment. The couple wrote about the encounter, explaining that Jay Z said 560 State Street was where, “[H]e started to gain real momentum in hip-hop . . . where he realized that he needed to cut out all the sh-t in his life and focus on his passion. While we waited, he spoke about how much 560 State had changed over the years–‘these trees weren’t here,’ he said. None of this was. He pointed to the impressive Viking grills that now lined the back wall of the courtyard, and joked about the make-shift grills he and his boys used to set up for cookouts.” Jay Z’s old apartment is just one example of a hip-hop landmark that has been gentrified in Brooklyn.

In KRS-One’s 2006 single “My Life,” the he spits:

“Brooklyn, no doubt, Wingate Park, no doubt/ Prospect Park I’m all laid out/Homeless, my gear played out and I know this/ But I’m an MC I stay focused.”

KRS-One is referring to the days when we was homeless and spent nights sleeping on benches in Prospect Park, a circumstance he mentions of in other songs like “Mr. Percy” and “Homeless.” During the time he lived on the streets, Prospect Park had an especially poor reputation. “The Park had developed a reputation as a crime-ridden home to drug dealing and homeless encampments, a dangerous place to be avoided. In the 1970s and ‘80s reportage on the park was distinctly negative. Local papers routinely reported on murders, bicycle thefts, muggings, and purse snatching in the park, deepening the park’s image as a social hazard rather than an environmental amenity.”((DeSena, J. 2012. The world in Brooklyn: Gentrification, immigration, and ethnic politics in a global city. Lanham: Lexington Books.)) Despite the jagged edges of Prospect Park’s reputation, its significance to KRS-One’s identity is important, explaining the struggle of young, black men who relied on themselves, and also addressing other issues like homelessness and neighborhood crime. This initial background led to his 1987 album, “Criminal Minded,” which is considered by many to be one of the greatest albums of all time.

The modern-day image of Prospect Park is practically unrecognizable compared to past photos, standing in sharp contrast to its former crime-ridden, drug manifested reputation. After a $10 million investment under then New York City Mayor, Ed Koch, the park underwent a major ecologic and aesthetic make over, and is now operated by a private organization called the Prospect Park Alliance that is in partnership with the city.((DeSena, J. 2012. The world in Brooklyn: Gentrification, immigration, and ethnic politics in a global city. Lanham: Lexington Books.)) However, the developments in Prospect Park are largely enjoyed by white, middle class families and is used as a marketing attraction for real estate brokers and developers who want to bring in higher-income residents.

As a result of gentrification, Brooklyn’s live music scene, part of the Golden Age’s lifeblood, has suffered as well. Southpaw, a popular music venue in the Park Slope neighborhood, was well-known for bringing a variety of musical acts, especially hip-hop artists, from Big Daddy Kane to Slick Rick to underground DJs and up and coming MCs. The venue was in business from 2002-2012, and was bought out by a New York Kids Club. Owner Matt Roff, explained the buy-out. “It would have been very difficult emotionally to see folks take control of the space if using it in the same capacity as we did. So after much deliberation with a few potential businesses we felt that the children’s business would use the space wisely and that the growing neighborhood around the club would eventually get great use from the kids club and hopefully appreciate the fact that its there and that we didn’t give it to Banana Republic or Starbucks.”

Though Roff is light about the club’s soft surrender to gentrification, the wave spread to other venues as well, such as Sputnik Bar, a popular hip-hop club in Bed-Stuy that closed in 2009 as a result of high rent prices. This is no surprise as Bed-Stuy, a historically black neighborhood, has seen a greater alteration in demographics over the years than even the rest of Brooklyn. “The biggest change in demographics over the last decade in Brooklyn occurred in Bedford-Stuyvesant, where the white population grew six fold and the number of African-Americans dropped by 14.6%.”

Wes Jackson, founder of the Brooklyn Hip-Hop festival, agrees that gentrification has had an effect on hip-hop music. “The bad part of gentrification is you get these invaders, and they come into your culture, and they re-write the rules. Hip-hop is living in a gentrified world where the barriers for entry that the creators set; too many white people couldn’t reach it so they get in there and drop it down.”

Hip-hop is a sonic record of the black experience. Its lyrics are representative of many of the oppressions and tribulations black people face in America, with special regard to urban poverty. Many Brooklyn artists during the ‘80s and ‘90s made mention of the struggles and issues facing their neighborhoods and communities, but also to the borough’s positive attributes that helped bring them up and shape their world view. “Rap music, more than any other contemporary form of black cultural expression, articulates the chasm between black urban lived experience and dominant, ‘legitimate’ ideologies regarding equal opportunity and racial inequality.”((Rose, T. 1994. Black noise: Rap music and black culture in contemporary America. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.)) However, with the displacement of blacks and Latinos, and the heavy influx of white and middle to upper class residents, characteristics of their beloved street corners and favorite spots cease to exist.

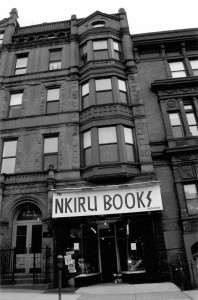

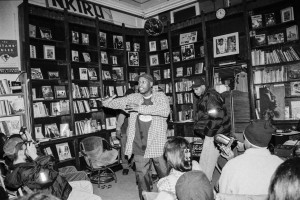

Before Brooklyn rapper Talib Kweli’s career took off, he worked in the oldest African-American bookstore in Brooklyn, Nkiru Books in Park Slope. The bookstore’s purpose was to serve youth, and emphasize work by black authors. Kweli credits the store for influencing his artistry and encouraging him to further pursue his rap career. “I was already into hip-hop real heavy . . . my style was already based in positivity and spirituality because that’s the type of hip-hop I grew up on, but working at Nkiru gave me facts and history, [and] information to back up some of the things I was rapping about. So my rhyme style became more factual, more informed when I started working at the bookstore.” In 1998, Kweli and Mos Def bought the bookstore from the owner’s daughter. They transformed it into an education center for the neighborhood. In addition to selling books, they hosted open mics, spoken word events, workshops, and lectures. However, due to financial stresses, competition from larger bookstores, and the rise of gentrification in Park Slope, the bookstore was shut down in 2000. Its old location is now Penny House Café.

[columns] [span6]

[/span6][span6]

[/span6][/columns]

Places like Nkiru were important because they promoted affirmative Blackness for the community. Nkiru provided young people a strong foundation and the resources to pursue the arts and stimulate their minds through knowledge and creativity. It promoted black authors and artists. The downfall of Nkiru and similar places hammers home the point that gentrification marginalizes both the physical and cultural aspects of Blackness.

Many artists throughout the new millennium have tried to channel 90s New York hip-hop, an ode to its influence as hip-hop has become the mainstream. Young Brooklyn artist Joey Bada$$ and his collective, Pro-Era (short for ‘Progressive Era’), seem to be trying to revive the hip-hop of the old days. With singles like “95 Til Infinity” and “My Youth”, Bada$$ lives vicariously through his hip-hop legends. His beats often feel akin to wayward Biggie Smalls tracks and his rap reference book is all 90s. The Joey Bada$$ approach to recreating golden age hip-hop and making it digestible for millennials is his attempt at revitalizing its sound, reminding listeners that Brooklyn hip-hop is capable of a resurgence.

Across the borough, a majority of gentrified neighborhoods have not been producing hip-hop or art on the same magnitude it once was during its prime. This is probably due to the fact that these neighborhoods have been corporatized for White consumption, with high-rise buildings and chain stores that already in exist in abundance. There is no room for Black cultural expression and creativity in spaces that have been occupied by materialistic-driven incentive. Hip-hop in Brooklyn has turned to its underground roots, producing music by younger artists that seek to recreate the sounds of past artists. But outside of Joey Bada$$ and his Pro-Era Collective, few current rap artists from Brooklyn have attracted audiences in the mainstream lens. Once you take the people out of the city, the sound leaves as well. Hip-hop is about place as much as it is about anything else. Nostalgia-ridden rappers are forced to take the mantle and play with the embers of something that flamed out long ago.

“Norwest Brooklyn (Greenpoint, Williamsburg, BK Heights, Clinton Hill, DUMBO, Park Slope, Crown Heights, etc.) was beginning to gentrify by 2000, and continued to gentrify in these community districts. Newcomer households are more likely to be white and Asian, wealthier, and more educated than established householders . . . newcomers are less likely to be foreign-born, and less likely to be black or Latino.”((DeSena, J. 2012. The world in Brooklyn: Gentrification, immigration, and ethnic politics in a global city. Lanham: Lexington Books.)) Yes, gentrification is causing Brooklyn to be cleaner, and produce better access to food, better education, less crime, and a heap of other wonderful benefits — but, for whom? Unfortunately, not the people who endured decades of negligence. When middle class individuals decided to take advantage of cheaper prices of homes and apartments in New York City, only then did the borough become relevant. Only then did the borough become safer, have trendy shops and restaurants, and persuade officials to take more active interest in its education system. Amidst this revitalization, the neighborhoods have not remained affordable for its present and long-time low-income residents.

At its core, gentrification is modern, urban colonialism; a continuation of systemic racial and economic inequality. It privatizes public space that previously bred art, and has been an effective eraser of Black spaces, places, and cultural structures. However, Blackness is in part resilience, and no art embodies that more than hip-hop. Hip-hop has proven that it is a flexible culture, as people across the world have adopted it, whether they live in the streets or in the suburbs, though its indigenous culture buries some of its roots in New York City. No matter where gentrification strikes, its former inhabitants are capable of creating a new art form, refashioning the destroyed eras behind them; rising above the surface like a flower from the concrete. It’s the Brooklyn Way.[/nextpage]