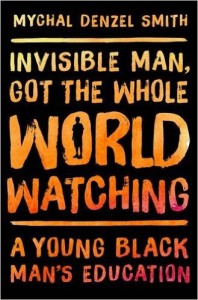

I have, for years now, watched Mychal Denzel Smith navigate often difficult topics with surgical precision. His approach to how we wrestle with black masculinity while also fighting for women’s rights, and the rights of people of color in queer and trans communities has always pushed me forward in my journey as both a writer and someone aiming to be as good of a person as possible. We had never spoken to each other before I decided to pursue this chance to talk with him, despite a familiarity with each other’s work. With his first book, Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching, releasing early this summer, I jumped on the opportunity to spend some time talking politics, blackness, and sneakers with one of America’s brightest young black intellectuals.

Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib: To start, I want to talk about your book. Is it out now? I saw you got copies of it.

Mychal Denzel Smith: It’s not out until June. I got advance copies of it, I was out in Denver at the American Bookseller Association Winter Institute, which is all of the independent booksellers coming together. I had to try and sell them on the book.

How did it go?

I was nervous. It was emotional seeing the book in a physical copy. So far for me, it’s been word documents and a pdf, so I hadn’t see a physical copy yet. That was big. Walking in there and signing books for all these people was overwhelming. People who had already read it, already gotten a copy, and were really excited and wanted to bring me out to bookstores. All the writing of this book was the whole calendar year of 2015, but this book, the idea and then proposal of it, has been with me ever since I began to write professionally. So to have that kind of reception this early on is making me feel less anxious about when it comes out in June.

I was nervous. It was emotional seeing the book in a physical copy. So far for me, it’s been word documents and a pdf, so I hadn’t see a physical copy yet. That was big. Walking in there and signing books for all these people was overwhelming. People who had already read it, already gotten a copy, and were really excited and wanted to bring me out to bookstores. All the writing of this book was the whole calendar year of 2015, but this book, the idea and then proposal of it, has been with me ever since I began to write professionally. So to have that kind of reception this early on is making me feel less anxious about when it comes out in June.

I’m still really anxious about the reception that I’m going to get from the public, because I’m trying to do some things in this book that we haven’t seen a lot of, especially with black men writing coming of age tales, or cultural analysis. We get stories of our experiences with racism, which we need. But also, I wanted to expand that conversation and talk about masculinity, sexism, homophobia, class, all of those things that make up identity.

I don’t know how the world is going to react at this point. We’re opening up space. We’re part of a generation of writers and activists and artists who are trying to open up that space. But in the book form, and cultural analysis form, I don’t know how receptive everyone is going to be, at this point.

There’s been some pretty good groundwork laid for what it seems like your book is reaching for, especially in the past two years. Do you think that helps do some of the heavy lifting?

The lane has definitely been opened up. And not just in the past two years. I mean, Mark Anthony Neal’s New Black Man was out like a decade ago. The space is opening up, I just don’t know how ready we are right now to have that honest conversation. Someone like Kiese Laymon, a great writer and a really good friend of mine, is opening up that space and doing it in the most imaginative ways. But the pushback is real. There’s a certain narrative that people are used to hearing from black men. I was a kid, and then I discovered racism, and then I overcame racism, and I wrote this book. It’s a very neat narrative that people are accustomed to.

It’s not that I’m saying anything really new. Obviously, black feminist women and queer folks have been challenging us on this for years, and now it feels like some of us are finally ready to step up to the plate. I feel the embrace from the folks making the challenge. But what about cisgender, heterosexual black men? How receptive are they going to be to someone not only telling their story, but also offering a challenge? Cis-hetero black men, in particular, don’t like to be challenged. Of course, it has to do with systems of oppression, and the world we walk through. That impacts the way we see the world and the opportunities we have. But being able to step back and look at the ways in which you’re complicit in systems of oppression is difficult for anybody. I’m curious for that reception.

I think about this a lot, especially in art and music. It’s like that new Macklemore song, which I listened to once and will likely never listen to again…

I haven’t even listened to it.

If you actually unpack everything, you realize that you haven’t reached a state of enlightenment that puts you at a higher place. You’re STILL complicit.

I don’t know if it’s important whether black people listen to it or not, but I’m interested in the idea of writing and creating while also giving into the idea that I’m complicit in these systems, and not exceptional. The “exceptional male ally” who isn’t like “those guys.” I think I’m constantly unpacking that, it never stops.

Definitely. You don’t want to be the person who is like I’m so different. I’m amazing. Look at how well I understand these issues. It sets me apart from everyone else. If you actually unpack everything, you realize that you haven’t reached a state of enlightenment that puts you at a higher place. You’re STILL complicit.

Exceptionalizing yourself is very seductive. To believe that you have reached a level of allyship, which is a word I’d like to get away from using, because it’s so wrought with connotations that I don’t want to be associated with, but the idea that I come to the table knowing where I stand, and that makes me special, isn’t real.

There are quite a few of us who still have our shortcomings, even with our understandings. We still fuck up. It’s about understanding, beyond this, that you’re a part of this ecosystem, and there is unlearning to do constantly. Stepping back and listening is the biggest thing that any of us have to do. We tend to think that we hear one person from a marginalized group, and we think we have the whole story and can tell the rest of the world what we know, because we heard it from one person one time. Engaging with groups we don’t belong to is a constant thing, not a one-time thing.

So it comes down to this: what parts of your privilege are you willing to sacrifice? That’s the question.

I’m glad you mention the complicated relationship with the word “allyship.” Truthfully, I’m not that far removed from the time in my life where me being called an “ally” publicly meant more to me than doing any work to suggest that I was on the side of anyone other than myself. It’s a seductive thing. It becomes a performative, public exercise that doesn’t hold a lot of water. I think the natural pushback, when you challenge people to go further, is “well then, how am I supposed to help?” And what do you say there? I have people who come up to me, and I’m sure this happens to you, and they say “oh, I read this thing you wrote, and I just felt SO bad. What can I do to help?”

I’m trying to get away from the language of “ally” because it means that you don’t have anything to lose. All you have to lose is honor, and prestige, and the praise associated with being an ally. Now, if you’re an accomplice, what are you willing to lose? An accomplice in a fight, is someone who is culpable as well. If we rob a bank together, we’re both going to do jail time. So it comes down to this: what parts of your privilege are you willing to sacrifice? That’s the question. And then you have to do the work of losing it. You have to give it away.

When opportunities come my way because I’ve written about queer theory, homophobia, or transphobia, and someone wants to interview ME about that, that’s a function of privilege. I need to give up that interview. I need to make sure the voices of people experiencing this are being heard. If that’s a PAID opportunity, are you willing to lose money on this? If you really are dedicated to this, you have to assess what you’re willing to lose.

In a capitalist system that is willing to co-opt movements, there’s so much to gain materially from privilege and power. How much of that are you willing to say no to? If you’re not willing to say no to the majority of it, then what is your actual commitment to undoing these systems of oppression? John Brown gave his life, you know what I mean? I’m not asking people to die for the cause. Someone has to live in order to be on the other side of oppression, but you have to assess what you’re giving up.

We’re both writers with books releasing this year, but they’re pretty different from each other. I’m interested in your writing process with this book.

The biggest issue I had early on was trying to prove to people that I deserved to write a book. I was trying to show people how smart I was, and that shit didn’t matter. The other thing was trying to figure out how to bridge all of these issues, and take everyone on the journey with me. It’s taking on the Obama era, so it’s an intellectual memoir that starts in 2004, the DNC speech, and it carries into adulthood. It’s about being honest, first and foremost. And then letting myself be honest with the reader.

I didn’t figure that out early on. Everything early on is really disjointed. It didn’t figure out how to make it all coalesce until I went to Ferguson on the year anniversary of the death of Michael Brown. Being there with the protests, the marching, with the police shooting another young black man, and then writing an essay about my time there. It came together for me, and what I realized for myself is that you have to bring people with you. That was what I took from that, and it clarified everything for me, and made the writing process smoother. It wasn’t always easy. I literally went bald writing this book.

I feel like we’re about to witness a lot of creative and artistic children being born out of this moment. I wrote the entire back half of my book staying up until 3am watching the live streams during the first summer of protests in Ferguson. I wrote another section just this past summer, watching everything unfold in Baltimore. I’m interested in the people who are tasked with archiving this in the same way we saw poets and writers do during the Harlem Renaissance and the Civil Rights movement. Do you feel central in that?

That’s a determination I can’t make for myself. But the movement is central for me. I’m trying to speak to this moment and contextualize things for people, because that’s what I do. I’m a writer. That’s my role to play. When I can, I organize and protest in the streets, but my main function is to be a writer and provoke new thought. I’m curious, though, did your book change? When you first planned the book was it something different, and then everything in Ferguson and Baltimore happened?

It’s about 50/50. The central theme of the book is about the non-material violences of gentrification, and the violences that get passed down through generations. In the middle of that, Michael Brown was killed, Ferguson happened, and America began to confront a more literal, touchable violence. I started to write about how all of these things intersect in communities. There’s a whole back section of the book that didn’t exist before Baltimore. I wrote them all in a month.

I’m curious about how we’ll look back on how much the intellectual trajectory has changed in this moment. Pre-Trayvon, the modus operandi was all about “unpacking blackness.” The main conversation, spurred by Obama’s existence, seemed to be about “you can be THIS type of black, or THIS type of black, and they don’t have to be in conflict.” Post-Trayvon, we’ve moved into the conversation that gets into the roots of racism and systems, as opposed to talking about blackness as an identity that needs to be interrogated in a certain way. There was this rise of a new class of intellectual with that shift in mentality, once we started talking about undoing these systems.

Well, yeah. There was a strong intellectual changing of the guard. There has been tension with that, and I’m always interested in how this black changing of the guard happens. How we can co-exist in these spaces during these shifts.

Those intellectuals come from a certain time period. The foremost black intellectual was appointed. They were the gatekeeper and the kingmaker. There’s a democratization of the space now, largely thanks to the internet, where we can enjoy a number of different voices. Voices that would have been locked out in previous eras. Real talk, Janet Mock would not have been an establishment person at one point. But her voice is so necessary. The voice of black trans folks are so necessary, and they wouldn’t have gotten embraced by the sort of establishment black political class. The fact that the internet exists means that these people have their voices heard.

It’s disruptive in a way that the older generation doesn’t understand. They think it’s a process of paying dues, and they think they’re supposed to have to anoint you. What we’re seeing instead is a flattening of that. You have a generation of writers, intellectuals, and artists, who WANT to share the space. We’re breaking out of the capitalist competition model which tells us that only a few of us can exist at a time. We don’t want to just hear from the same charismatic black male figures over and over again. We want black women, black trans folk, to be at the forefront of this. Some folks from previous generations understand that. Some don’t get it, and are resistant to it.

We’re breaking out of the capitalist competition model which tells us that only a few of us can exist at a time.

It goes back to what you mentioned about giving up power, I think. If we’re being honest, it’s still black male heavy. But it’s not only black men, which is something that makes me comfortable in a way. I feel like the movement, and the intellectuals of this era do a better job of reflecting my generation. The people I see in the streets. The people I see at my readings.

Since we’re talking about guard changes, are you more cynical now than you were when the Obama era began?

It’s funny…I’m more optimistic now than I was then. I was a complete cynic. The start of the Obama era was my early adulthood. You think you’re smarter than everyone else, you’re making this simplistic analysis of our political systems, and you think you’re really profound. I’m certainly not in that place anymore where I think that nothing can be done.

I’ve witnessed this movement happening, and that’s what gives me hope. I watched a generation of folks who have been called apathetic all of our lives, and I watched a generation turn that on its head in response to the most visceral and upsetting forms of violent racism being captured for the whole world to watch. We’ve been activated for a while now. We’ve been activated since Katrina, but it didn’t turn into a movement until the killing of Trayvon.

It was the coalescing of a lot of different things. The rise of social media, the voices of black women being heard, Trayvon being a figure we could rally around. Watching the last four years, the people who did show up for Obama, showed up and voted for him the first time, they’re saying “America promised me some change. Promised me that this was going to be different. And it’s not. So it’s time to rise up.”

I oftentimes think about the limits of a presidency, too. The first time I voted for Obama, I remember feeling like he wasn’t a politician. Like he was something more. Kind of how we’re seeing Bernie being sold now. Even still, I watched the last State of the Union, because I thought it would be “different.” I felt sad because not only has nothing changed, but this may also be the best presidency I get in my lifetime. And now we have to make a decision on who to replace him. What’s your hope for the remainder of this political cycle, as we make that decision?

I hope we become less invested in who is president. It’s exactly what you were saying. This is what we can get right now. Obama may be the best president of our lifetimes. And I’m not talking just right now. Hopefully I live a long life, and I may never see a better president. Think about what that means. I’m witnessing a president who cannot talk about racism, and even when he did, it was tepid and evenhanded. His only racial justice program was My Brother’s Keeper, which was only a mentorship program. And this is the best we can get.

But it doesn’t have to be, if we can divest from the symbolism of the presidency and what it can get us. If we invest in the movement and in fighting against the systems in place. Just on the Democratic side, are choices are Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders. You have a candidate who can likely win, and might do some things in office, but most of her politics are awful. And then you have Bernie Sanders, who, he’s the most left of anyone who has a viable shot at this thing. And if you elect him, in our current political landscape, he can’t actually accomplish anything. All of his agendas will go to congress, and nothing will make it out of a republican controlled congress.

When we think about the long list of issues with the American political system right now, we have to think about the fact that it’s not a president who comes in and changes those things. It’s us demanding those things be changed, from the local level on up. At this point, we really have to look into redoing the whole political structure.

I’m asking the question: What about these systems work, and what doesn’t work, and is it worth saving? I don’t know if the American system of government, as it currently stands, is worth saving. I don’t think that we need to keep investing in it over and over again. We can have a new constitution. We’re still working with the one that said we were 3/5 of a human being. We can get a new document and put the old shit in a museum. I don’t understand the resistance to change when we understand the system doesn’t work for us. I mean that from all angles, not just the left. People on the right, the reactionary forces don’t feel like the system works for them either. Why don’t we just come up with something new? And maybe that involves divesting from the project of the United States of America. What if 50 states broke into their own countries, governed themselves accordingly, and we didn’t have this overarching United States of America? I’m not saying that’s the answer, but I’m saying that new things have to be put on the table right now.

I’m asking the question: What about these systems work, and what doesn’t work, and is it worth saving?

Can we talk about sneakers?

Yeah, I just had some delivered.

There aren’t many writers I know who I can also talk sneakers with. There aren’t many PEOPLE I know who I can do that with now. The concept of being really passionate about anything, as you get older, kind of fades out, or becomes a joke to people. Still, what did you buy last?

I think a pair of Air Max 95s, the Stussy collaboration. The green joints. And then I got some low top Jordan 5s. The Chinese New Year ones. What I love about sneakers is what they allow for, stylistically. I could wear the same outfit every single day, right? White t-shirt and jeans, everyday. But if I put on a different pair of sneakers? It’s a different outfit. They bring together an outfit in a way that you can’t do with what you wear on the rest of your body. Sneakers are the center. I come up with what I’m going to wear based off of the sneakers I choose.

From an emotional and nostalgic standpoint, we grew up with Jordan marketing all these sneakers to us. It’s all connected to so many memories of watching him do amazing things in these sneakers. So many of us wanted to be Michael Jordan. Biting our tongue on the court because we couldn’t play with it hanging out of our mouths, trying to perfect a fadeaway before we even got our jumpshots down. That’s who Jordan was for us, and that’s where sneaker culture was born. And then it became a competition. Who is the freshest? Who has the most obscure joints? I remember being in school when everyone was messing with Jordans and Air Force 1’s, and so I went and got a pair of New Balance 574s because no one was messing with them at the time. It’s all about standing out.

Even now, I feel more confident when I wear a fresh pair of kicks. I walk with my shoulders straighter and my head higher. I finished writing my book, and I had a pair of Bordeaux 7s on. That pair of shoes will be special to me forever. Kicks can be meaningful in that way.

As a sneaker owner now, I purchase differently. I’m really into nostalgia purchases. The shit I couldn’t ask my parents for when I was a kid, because I didn’t grow up with a lot of money. I’ve gone to some great lengths to find stuff that I get, and then get real nervous about wearing. So I gotta ask, what is your favorite sneaker of all time? The one you’ve always treasured?

Right now, if you ask me, because I just wore them, it would be the Bordeaux 7s. And I didn’t think I liked 7s that much, you know? The whole African art inspired 90s thing wasn’t doing it for me. But then you put them on, and the color scheme, there’s something about that. Still, I love my Jordan 14s. The “Last Shot” ones, mostly for the nostalgia. I watched him make that shot in those, and instantly wanted a pair.

If I’m going to say my favorite, non-specific, but just out of the Jordan models, I’d say that I like the first ones. It’s the cleanest design, classic shoe, you can wear it anywhere, with any kind of outfit.

I love Jordan 11’s, but I always find myself uncomfortable about wearing them. They’re beautiful shoes, but patent leather isn’t great to maintain. It’s like you can wear that shit in the house and ONLY in the house.

I love 11s, but I feel protective when I wear them. So then I ask, “Why am I wearing these??” The Black and Red 11s actually may be the greatest sneaker of all time. And, like you, my parents wouldn’t get them for me when I was a kid. They were like “we’re not buying patent leather for no child!” so, being able to have them now is great. But I’ve worn them twice, and I’ve owned them for like a year. I got them with my check for my book advance. It was a present to myself. I’m protective over them. I don’t want anyone messing with them, but I want people to see them. I want to be seen in them.

You have to take into account that black people are still living this idea of being Ellison’s Invisible Man, right? And what do we do but try to take up more space and be more visible. When brothers are wearing those bright colored suits and gators, they’re trying to announce their presence to the world. And that’s what we do with sneakers. We just try to be more seen.

Mychal Denzel Smith is the author of Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching (June 2016)(alternate link), a Knobler Fellow at The Nation Institute, and contributing writer for The Nation Magazine.

Comments

Awesome interview! Definitely buying the book too!