On my best days, I walk with my head held high—over or beyond the mystifying childishness that makes a white man wonder if I belong in the airport lounge sitting next to him; or even (though it is a far harder head holding to manage) over or beyond the incomprehensible savagery that makes white police officers shoot black people like safari game, even when they have no intention of eating them for dinner. But there are days when the morass of insanity that only racism can produce fumes more expertly than I care to acknowledge, making me want to spit on the man who is suspicious of my presence in the lounge; or to shoot delicious, unbridled rounds of bullets into the chests of those thugs-cum-police officers, certain (like they always are) that I will walk away untouched and unchallenged, as if I had merely uprooted a weed.

The racist white man bequeaths his children something more ineluctably dear than a seat at the table when their black peers are not even permitted inside the restaurant. Yes, the white college rapist smiles with haughty relief when he realizes his skin color has saved him and his brothers once again, but he knows inside that there is some world (and it might well be his grandchildren’s world) in which his promising swimming career will mean nothing when he decides to do as he pleases with an unconscious woman. He knows that that kind of power—to dodge all the bullets that should have hit him squarely in the chest—is always in danger of extinction. He knows that he will not always be able to hide in a womb of mediocrity and still get what he does not deserve. He will still feel a jolt of ecstasy when he shoots at a car of carefree black teenagers, but he knows, like sweat silently dripping down your back tells you it is hotter than you thought, that wholesale murder will not always be in vogue.

What, then, is useful about racism after that?

For, a man who is afraid of you may muster the courage somehow to knock you down, but a man who believes what you have said about him will not even try.

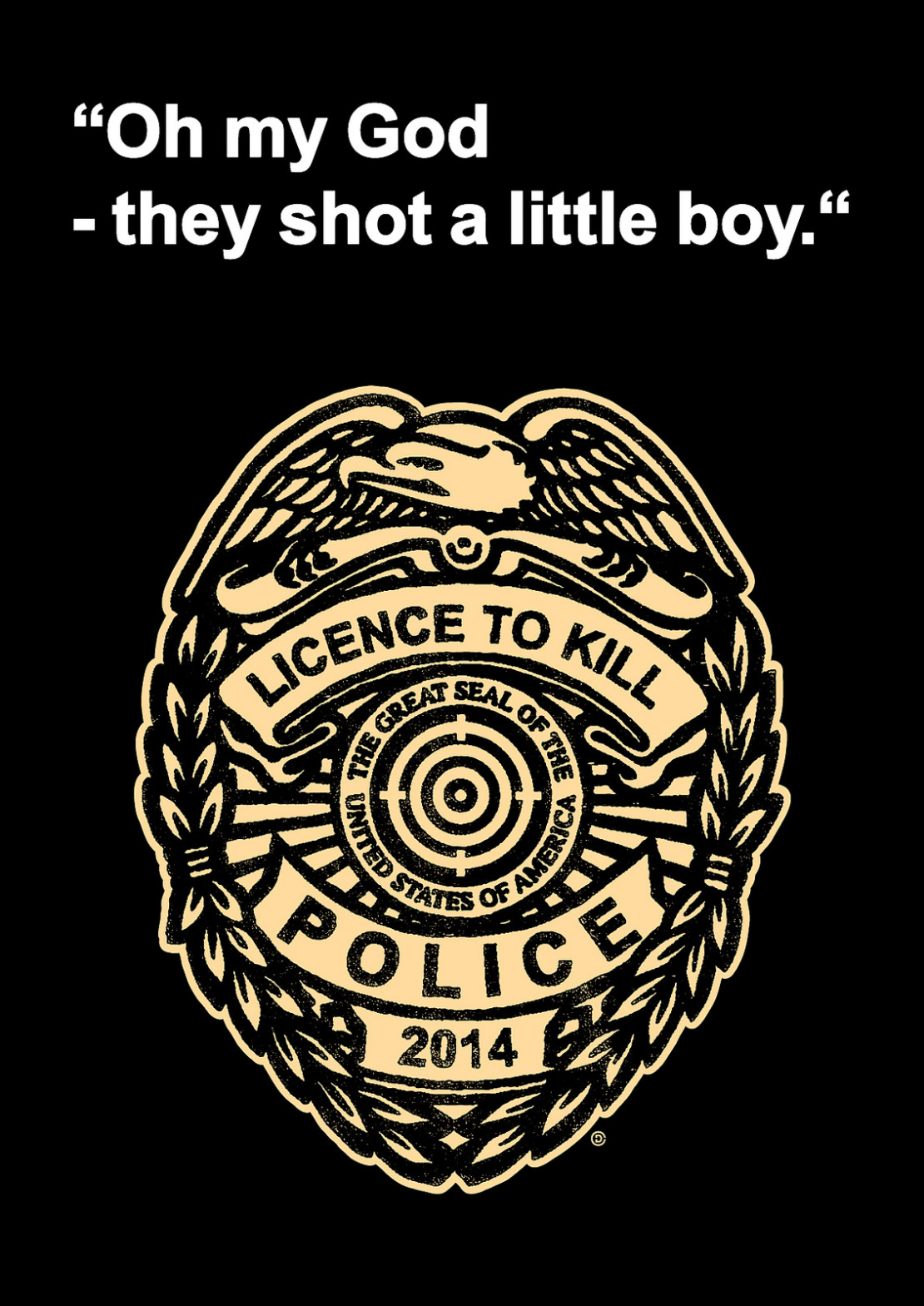

Murder, it seems to me, confers such a sense of exhilaration upon the murderer that he scarcely has time to wonder what he has done before he is convinced, like the terrifying god of Genesis, that the work of his hands is “good.” Never mind the blood or the fat silence that stops time if only for a moment, the racist cop retires his gun to its holster instantly pregnant with a library of justifications before he even returns to his car. And in the gust of the gait that propels him casually onward—to his car, back to the precinct, and later guiltlessly deep into the folds of his bed—there is a vision of the world left entirely undisturbed: the victim is black; the victim is guilty. I am white; I am blameless.

He cannot rightly recall when he first knew that, and he is even less sure when he no longer needed to verify it through his own experiences. But he is certain nevertheless. Yet, let us ask him: Was it when his mother grabbed his hand slightly more tightly when they entered the grocery store as two black men walked out? Was it his father, waxing poetic over dinner about all the children “they” have without being able to support them? Was it running alongside the black boys on the track team, when—stunned by their prowess—he silently vowed to beat them one day? Was it driving through their neighborhoods, mercifully on the way to somewhere else? Was it the twenty-seventh time he saw a black suspect on the news who had done god knows what again, or the black woman—hair uncombed, defiant of all social graces—the reporter gleefully presented to the camera, asking questions she could barely feign an interest in? Was it the confusing self-pity he felt when his girlfriend’s eye wandered ever so briefly as a black man walked by and had the strange kindness to say hello? Was it the thing his teacher said about African American novels being a little grittier than traditional literature? Was it one of those movies in which the black sidekick always deferred power to his handsome white friend, all the while grinning with delight? Or was it simply the feeling he always had that it was quieter in his neighborhood? Alas, he doesn’t know. But there it is before him: a reality, with tentacles of hypnosis so unimposing he hardly knows they’re there. So his mind simply grows within them, until the consummation is complete with the finality of a cancer.

His brothers and sisters don’t know when the image of their superiority first presented itself to them either. And sometimes they feel the guilt of their privilege like a siege of indigestion. But there is medicine for this: their parents did work hard for everything they had, and did manage to succeed in America despite ungracious odds. Or, they were better behaved than their brown friends, who always seemed mad about something, who always had a chip on their shoulders so that you couldn’t say anything that wouldn’t offend them. Or, those people did seem irresponsible with money, wanting more for free than it appeared they were willing to work for. There was more crime in those neighborhoods. They were better at sports and music. Their babies were prettier and lovelier until they grew up.

Murder, it seems to me, confers such a sense of exhilaration upon the murderer that he scarcely has time to wonder what he has done before he is convinced, like the terrifying god of Genesis, that the work of his hands is “good.”

As long as this heady reinforcement was always in effect, they could live in an Eden of their own creation—a place so “good” it was impossible to think otherwise, even if from the lowly humans’ perspective it was always rigged for failure.

And that—beyond the satisfying crush of the baton on the black grandmother’s head; or the orgasmic stroke of the political pen that introduced the war on drugs—is the use of racism. It is the power to create a reality that black people must respond to despite their best efforts to ignore it. Eventually, even black people start to believe the reality broadcast insistently before them. And that, the racist knows pathologically, is better than the power to cause fear. For, a man who is afraid of you may muster the courage somehow to knock you down, but a man who believes what you have said about him will not even try.

So, I will find myself in an airport lounge thinking I have outwitted the white man’s opinion of me, but he will remind me with just the raise of an eyebrow that my world is not at all what I think it is. And I will spend the rest of my time seething with fury, ready to tear his flesh from his limbs, while he crunches on his carrots and sips on his wine, having already blinked me into irrelevance because, in only two seconds, he has created a reality for me yet again.

Another black man will similarly be convinced that, in his car with his girlfriend and daughter, he has a sovereignty immune to the outside world. But he will have forgotten that he left the house with a broad nose, a trait impermissible to his independence and objectionable to the fragility of the white police officer’s world. What does it mean to the racist cop that this black man rides through the world naked in all of his blackness, as if he hadn’t been told to avoid eating from that tree? It means, of course, that fear is not enough, and he will need to be beguiled back into submission. The black man will need to be reminded, then, with the sportive punctuation of cold-blooded murder, so that the mistake of Eden for everyone is never repeated. And as he bleeds onto his girlfriend, dying in the time it takes to boil water, his girlfriend, and all her extended black family across the country, will return to a nightmarish reality they thought they had outpaced.