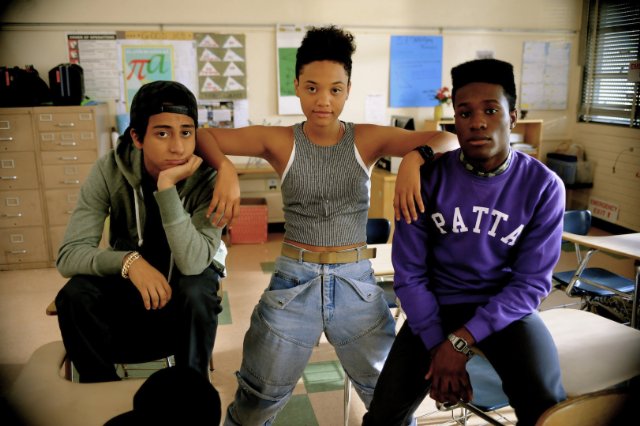

Recently, I went to see the film Dope: a movie that’s reminiscent of the 80s goofballs-get-into-wild-misadventures genre of broad comedies. The film follows a high-school senior named Malcolm (played by Shameik Moore), a socially awkward kid with an obsession with the 90s that he shares with his two best friends Diggy (Kiersey Clemons) and Jib (Tony Revolori). The three kids are also part of a punk band (though punk is really a stretch based on the music they play) and are generally good students. Early in the film, Malcolm earns points with a drug dealer named Dom (A$AP Rocky) by being a messenger between him and an old girlfriend, Nakia (Zoe Kravitz). Malcolm and his friends get invited to Dom’s birthday party, which ends in a police raid. In the chaos to get out of the party, Malcolm’s backpack gets stuffed full of drugs, leading to various hijinx and movie wackiness for these three in-over-their-head characters.

Dope is a cute adventure story: it has its moments that are charming and even laugh-out-loud funny. As a teen comedy about drugs and shenanigans, it’s just fine; the biggest gripe to be had with the movie is that it wasn’t content with just being a silly teen romp, but instead felt the need to use this story for a larger thesis statement on blackness.

You see, Dope is also a movie about the perceived animosity towards the Black Nerd and what it’s like to be a kid who’s “not like the other kids.” This is an attitude that the movie takes a lot of time to spell out for you over and over again. Malcolm and his friends (but Malcolm especially) get teased and beat up consistently for, what the movie colorfully suggests as, their interest in what the narrator calls “white people shit,” like manga, punk rock music, getting good grades and applying to college—this is not labeled as nerd shit, by the way, it is specifically cited as White shit—and not for the simple fact of them just being uncool. Though it’s not explicitly mentioned, you have to believe their fixation on rap music and culture from the 90s is also a tool used to further separate themselves from the herd and highlight their specialness. Your empathy and sympathy for these characters is based on the typical nerd persecution complex of girls not liking them and bullies beating them up for being smart. In fact, education is used as the crux of the us-versus-them logic on display. Everyone who’s meant to be positioned as “different” in the film is so because they’re “book smart” and trying to get into a college. In Nakia’s case, this is her only real character trait.

This is a high school movie with high school-level thought processes on race that it tries to pass off as enlightened and appeases the sensibilities of existing white liberal ideas on the topic without offering any sort of self-awareness. In this movie you’re either a nerd or a gangster, and the novel idea this film has about gray areas is that, “well maybe you can be a mix of both.” It’s static and lazy thinking, especially coming from the filmmaker, Rick Famuyiwa, who already made one a great coming-of-age film about high school kids, 1999’s “The Wood”. None of the characters in that film would fit in the boxes made in this movie and that was the beauty of it. It just felt like a story about kids growing up.

One of the executive producers of Dope is Pharrell Williams, which is notable in light of Pharrell’s aggressive branding in the past year and a half as someone who claims to be a “New Black,” someone who has moved beyond the limitations of race and is using his personal feeling of uniqueness as an argument in favor of a new progressive, bourgeois idea of Blackness countering the monolithic stereotypes of what Blackness is perceived to be. While this feels genuinely well-intentioned (even coming from Pharrell) but it’s coated in an air of condescension and self-aggrandizement. In a fit to differentiate from perception, we end up silencing, belittling, or resenting our brothers and sisters who we feel are part of the problem. Dope is sprinkled with this same tone in its conversation on blackness. It’s very apropos that this film has this conversation within the trappings of a high school setting, because it’s there that many of these issues crop up. Often when someone makes the argument that Black people don’t value education and instead romanticize violence and stupidity, it always seems to come back to when these people were in school and observed everyone else around them making poor choices whilst feeling that they were unfairly maligned for being who they were. I’m not here to tell anyone that their experiences were wrong or nonexistent but it is odd to base bold, generalized statements about the nature of most or all Black people on your childhood experiences, knowing fully well that 1) children at that middle/high school age are awful and 2) the world is bigger than your hometown.

Ultimately, the big lesson this movie is going for is the idea that Black people can be complex human beings. Malcolm is a nerd but he can also be a tough guy but don’t forget that deep down he’s just a nerdy regular kid like anyone else. It’s nuance in the way that Brad Paisley and LL Cool J’s “Accidental Racist” was nuance.

This sort of thing is old hat, though. For as long as Black people have been making art they’ve been tackling blackness, with regard to what makes an authentic black person and how to perform in this skin. Consider Paul Beatty’s latest book The Sellout, a tough, maddening and incredibly funny satire of American culture: integration, urban plight, police, black militance, masculinity, class, etc.. The story follows a sheltered young man who, fuelled by the deceit of his family and the general disrepair of his hometown, enlists the help of the town’s most famous resident—the last surviving Little Rascal, Hominy Jenkins—and decides to reinstate slavery and segregate the local high school, landing him in the Supreme Court. Beatty’s book is dense; aimed at every facet of Blackness, the U.S. Constitution, the Civil Rights Movement, and the common sort of sociological observations about the ways in which we lie to ourselves as people in order to get through the day.

There are parts of The Sellout that truly get underneath your skin–which is Beatty’s intention–and can lead you to shrink away from the point being made, but ultimately Beatty doesn’t seem particularly interested in advocating for a particular brand of Blackness. Everything is up for criticism and even dismissiveness for better or worse; The Sellout is articulate and specific enough in its approach to at least make for a well-thought out take on what it means to be a Black person in America—in both offensive and smart ways. It’s also hilarious and its wit buys it a lot of goodwill. While it thrives less on being a conversation piece than just being absurd, it proves to be more deft and piercing in its take on race and the performance of blackness. A movie like Dope feels underthought by comparison; a sort of first draft contemplation on race.