People these days are increasingly characterizing pop culture as having entered the “age of the booty”. Read a couple think pieces and you’d think twerking was a special magic only revealed to us a couple years ago. Talk to a black girl anywhere in the world, however, and they’ll tell you that’s nonsense. There hasn’t been a time when black women haven’t celebrated our bodies, even when we’re told not to. But since our lived experiences seem to be irrelevant, much analysis has emerged to make sense of why we might love this part of ourselves.

One such article, published recently in The Atlantic, analyzes the videos for Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda” and Jennifer Lopez’s “Booty” through the lens of same-sex female desire. The author, using examples dating back to the Victorian age, places this new fascination with booties and twerking beyond the male gaze, and argues that artists are alternatively winking at or outright exploiting female desire in their work. It’s an interesting lens of analysis, and I can’t argue that it’s not sometimes at play.

I have experienced this distinct joy and excitement watching friends and family members practice their dances over the years, and I suspect that something similar is at play when girls twerk with their friends at parties, obsess together over Beyoncé videos, and share pictures of Instagram models.

That said, I can’t help but feel like there is something else going on, something that might be specific to black women that others might not pick up on. Without erasing queer experiences, I think twerking, and the centuries-old celebration around it, is rooted in something that is less desirous and more uplifting. Women celebrating women being women. Though there is an element of envy, there exists a deeper, genuine joy in seeing another woman being her best (physical, but also mental and emotional) self. Tokyo Vanity’s original “That’s My Best Friend” video demonstrates this better than I’ll ever be able to explain.

While you can observe this celebration of womanhood among any group of girlfriends dancing in a circle at the club, what put it in sharpest relief for me is watching “ragees al’aroos”, or the bride’s dance, at Sudanese weddings. My family is from Sudan and we’ve lived there in the past, so I’ve witnessed the tradition many times. Occurring on one of several nights of celebration, the dance is an ancient custom wherein the bride performs up to 100 different prescribed dances to a variety of songs. Much of the dancing, though specific to Sudan, is reminiscent of what you might see in your average twerk team video.

… artist and actual twerk scholar Fannie Sosa talks about how twerking originated as a fertility dance done in circles where women celebrated and taught each other.

On this night, the bride is rather scantily clad, as one of the main goals of the night is to show off her body and what it can do. The audience is exclusively women, though it was a mixed-gender event before Sudan’s recent conservative shift. The bride has practiced her dances for months, and simultaneously worked on beautifying her body, and so by the end she is at the pinnacle of her womanliness, ready to show off and be celebrated (and of course critiqued by the less pleasant members of the audience). The groom is present alongside her, but he invariably ends up being forgotten.

Jennifer Thorington Springer’s analysis of Calypso music, and specifically the work of Alyson Hinds, is relevant here. She explains how Hinds’ music creates spaces where women become subjects, and “where one’s wining skills can be showcased,” inviting the audience to “validate [her body] as beautiful and to celebrate its form.” In reading those descriptions, I was struck by how closely her characterization of the music and performance mirrored what I see in Sudan. There, too, the bride asserts herself as the subject through the music and movement. The significance of this act, and its ubiquity across black cultures, is rarely acknowledged.

The audience also plays its part: the assertion and admiration of beauty and skill is in the air as the bride’s family and friends sing along and cheer for her. I have experienced this distinct joy and excitement watching friends and family members practice their dances over the years, and I suspect that something similar is at play when girls twerk with their friends at parties, obsess together over Beyoncé videos, and share pictures of Instagram models. We’re celebrating women being their best versions, and maybe also encouraging ourselves to achieve the same.

Without erasing queer experiences, I think twerking, and the centuries-old celebration around it, is rooted in something that is less desirous and more uplifting.

The absence of men doesn’t mean they don’t matter here. Ragees al’aroos is part of a wedding, after all, and is centered on the bride’s body as it relates to her future with her husband. Twerking, though not at all exclusive to parties and strip clubs, is associated with attracting men. There is something liberating about being a woman among women celebrating women, but because it is still contextualized in the male gaze, the feeling of liberation – despite its potency – is called into question momentarily. Is it a good thing to celebrate a woman’s conformity to her gender role? Or does that feeling of joy and liberation overshadow the role of men and render them irrelevant, like Drake sitting helplessly at the end of the “Anaconda” video?

To that point, artist and actual twerk scholar Fannie Sosa talks about how twerking originated as a fertility dance done in circles where women celebrated and taught each other. Over time and through the influence of patriarchy and white supremacy, that aspect was lost and replaced with connotations of impropriety and vulgarity – ratchetness if you will. It became so taboo that the Mileys and Taylors of the world now use it to shock and awe. Despite this, the positivity around twerking remains thanks to the perseverance of black women across the diaspora, and it still carries those connotations of fertility. We see it in Sudan and across Africa, and we see it across the ocean in America and the Caribbean. Black women continue to derive joy from twerking in the same way we have continued to derive joy from so many things we are told we can’t – by doing it together.

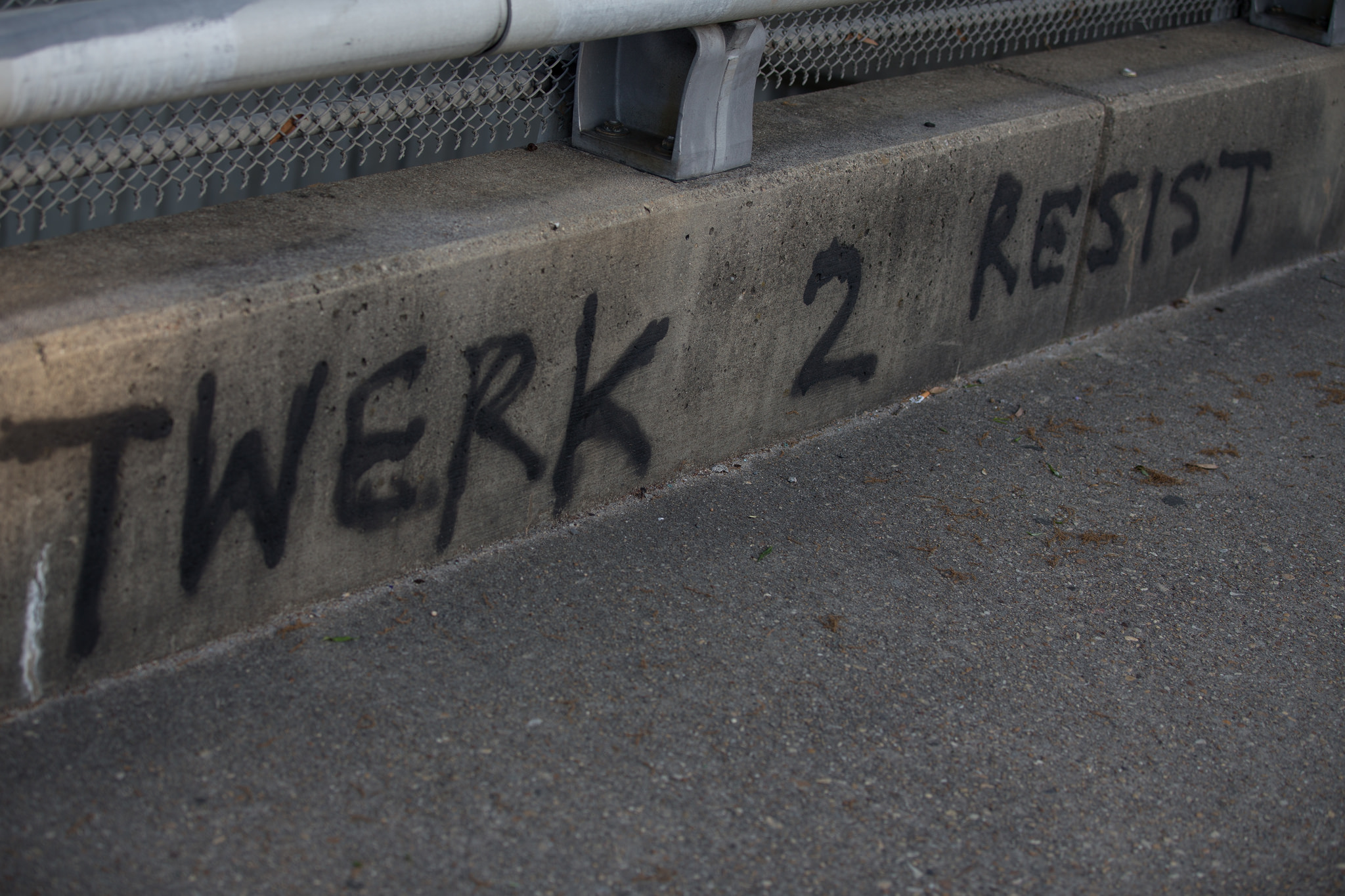

Photo Credit: Tom Woodward