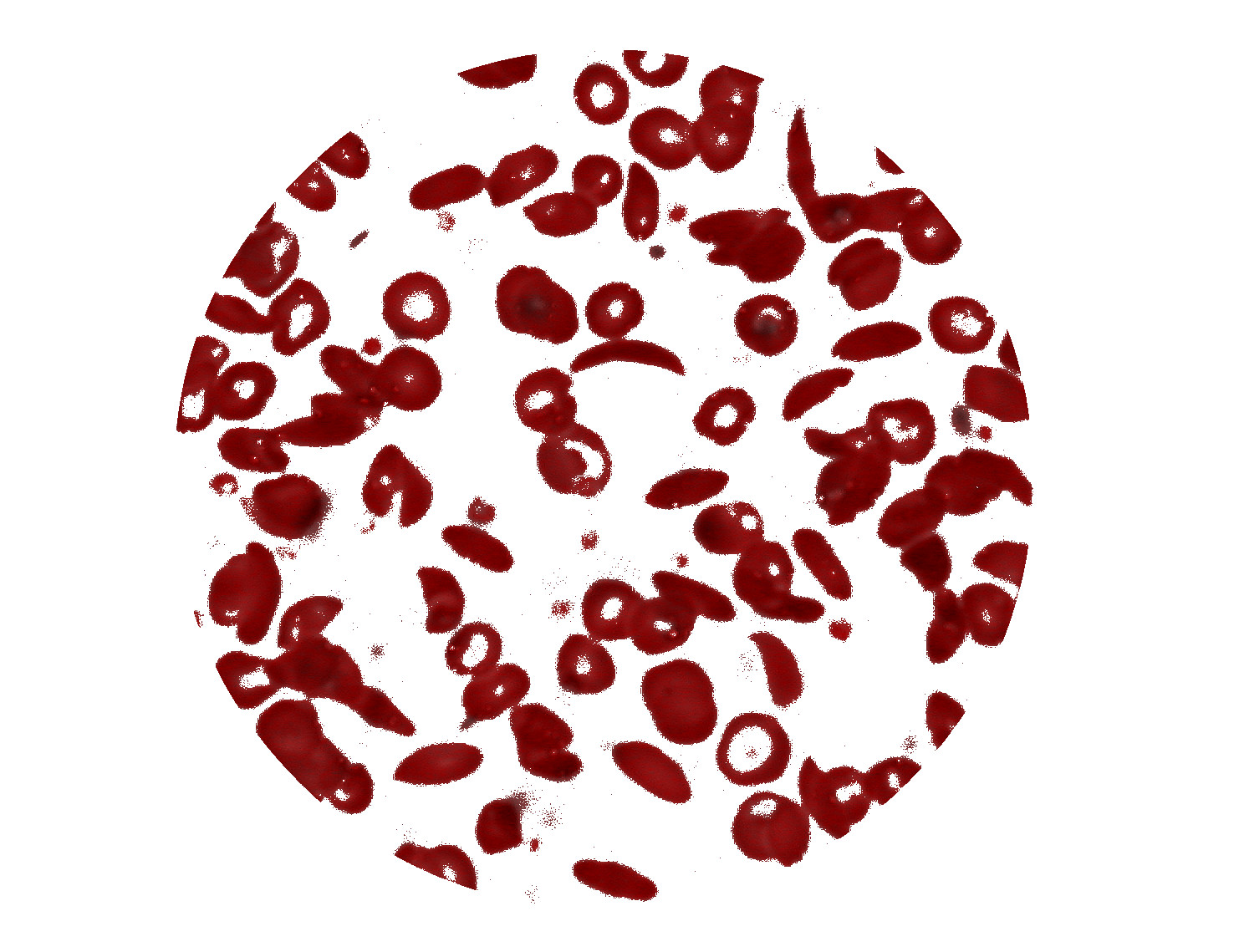

Technically, I have sickle cell anemia.

“Technically,” because I have a condition that should put me in the hospital every week from weariness and intense pain, and yet I’ve somehow been lucky enough to live life mostly free from these symptoms. I’ve seen people ravaged and worn down by this disease, going in and out of hospitals, hopped up on constant medication, a constant stream of pain being taxed onto their bodies. Plenty of progress has been made towards managing this disease, but since childhood, I’ve known that to make it beyond my 20s would be a blessing.

I try to put this anxiety in context. As far as I knew, I’d never have to deal with it. I always believed I’d be safe and that time was on my side. Even at 11, when I made my first hospital visit, I never thought seriously about sickle cell affecting my life. I was extremely fatigued for a couple of days and it got to a point where I could barely walk. I then went to my primary doctor and found out I needed to go to the hospital for a blood transfusion.

As I typed out those words, I realized that a blood transfusion is not a small thing for an 11-year-old. It was the first major medical procedure brought into my life by the disease, but at the time I saw it as a passing whim.

Nothing else happened until a few years later when I had my first severe attack. I was in the most excruciating pain of my life. The pain hit me from every direction; my insides felt twisted and pulled. It was so bad that it started to play tricks on my mind. I was delirious, unfocused, trying desperately to disappear from the current reality.

This was my first attack, but I didn’t yet know that. All I knew was the pain. I kept thinking, “Is this it? Is this when I die?” I thought of all the things I’d never gotten the chance to do, the things I’d never do and all the words unsaid; I truly didn’t know if I’d make it. I slowly pushed my body towards my parent’s room and with exasperated, clogged breath, explained what was happening. My parents drove me to the hospital around 3 am. While there, the doctors explained to me that what was happening was called a “sickle cell crisis”.

My first thought, honestly, was that I had to make sure this never happened to me again. I needed to drink water regularly and take preventative measures to not go through this pain again.The doctor explained that sickle cell crises were prone to happen to people with sickle cell anemia, but despite this explanation, I thought of it more as a freak occurrence. But as I sat on that hospital bed with an IV in my arm–numb from drugs and lacking acknowledgement–that freak occurrence embedded itself as a part of my life.

From then on, I was in the hospital at least once a year. In college, with the stress of classes and campus activities, it happened even more frequently. Significant, yet manageable, pain would strike my lower back, or abdomen, or groin. And I’d tough through it. These moments invaded my mind and my behavior. The thoughts of, “is this how it ends,” went from infrequent to weekly to daily. With every new attack, that brief moment of wondering whether this is the one that’ll end it all happened so often that it became part of the routine. Pop a painkiller, prop up a pillow and contemplate whether death is coming.

The pills certainly don’t help. They keep you woozy for long stretches and they fuel some intense lucid dreams. Usually the dreams involve waking up before being hit by something powerful. The most recent one involved being on train tracks with a train barreling towards me at full speed. Like an unconscious manifestation of my paranoia, death (or at least pain) comes for me quickly and violently.

Throughout my life, I’ve met and known many people who had sickle cell anemia. I’ve seen it ravage people’s bodies to the point that they were in and out of the hospital on a weekly basis. I’ve seen a young woman push her body to stand up in a church as though a boulder was strapped to her back, just so she could testify that she’s alive to see another day. I’ve talked to a friend as she laid in the hospital, fatigued and agitated by the fact that the drugs the doctors had given did nothing for the pain. As I stayed on the phone with her, she did not betray fear but an understanding that this is what it is: another routine. I’ve listened to stories told by adults around me of family members they’ve lost at a young age (around the age I am now) because of this disease. And yet, I’ve also talked to people who, like me, feel like they got spared. They’re not in the hospital each and every week or month – sometimes it’s just once a year – and if they’re lucky, they might go a whole year crisis-free. We are few and we realize how blessed we are.

Since childhood, I’ve known that to make it beyond my 20s would be a blessing.

My friend Shayla and I have bonded the most over two things: filmmaking and having sickle cell anemia. A relationship forms quickly between two people when they both share something like this. Like being a member of a secret society and running into a brother, you instantly feel like lifetime friends because you both know what the other has been through. We talk about our hospital trips, natural remedies we’ve tried or are trying; we check in on each other to see if we’re feeling any pain. On road trips, when I had to crash on an inflatable mattress, she always wanted to be sure my body wasn’t affected by the uncomfortable conditions and that I had my pills on me in case. I’ve done the same for her. Through our struggle, what is maybe the best part is that we’ve employed humor to cope as we support one another,laughing about our situations to keep sane and hopeful.

Another friend of mine, Chloe, is always concerned about me. She calls me to see if I’ve been stable and I call her for the same reasons. We have conversations about how the weather makes our joints ache and we give reviews on the pills we’ve been prescribed most recently. I act tough about what I go through just so I can show strength for both of us. She uses dark humor and ambivalence towards death as a defense mechanism to handle the constant pain. We both worry about each other more than ourselves. Plenty of my friends have helped me out and taken care of me in different ways but they fit into two categories: people who are overly concerned about me and people who aren’t concerned at all. The beauty of meeting other people with this same disease is that I feel intrinsically understood. It’s the only time in my life so far where I feel an implicit connection with people.

Death is a constant. It is the only thing truly guaranteed in this life. The attitude towards death, though, is similar to taking out loans for college in your freshmen year: your day of payment is coming but it’s a ways off. When you have a disease that can take your life, that life now constantly feels like senior year with graduation coming any moment. My body gets weary and aches in ways it shouldn’t for another 10-or-so years. My friends and family are concerned about me in ways that, even if I wanted to act like I’m going to live forever, are reminders that there’s still a dark cloud over me. Again, I am around the age that people with this disease have been known to lose their lives. Thanks to modern medicine and luck, I’m still here. Death is on my mind when I go to work at a job I don’t particularly care for, but at least it comes with the health benefits necessary for me to care of myself when my body goes into crisis mode. I live a mundane life, and I spend my nights using any creative outlet as an escape from it. Sometimes I will research natural remedies and medical breakthroughs online.

In movies, when people are told they’re going to die, they always use it as a means to do everything they’ve ever wanted to do before that fateful day comes. Every ache or strain I feel in my back or abdomen or groin is a reminder that death is always over my shoulder; you’d think that this would foster an attitude of “carpe diem” and always making the most out of each day, but it hasn’t. This is ,in part, due to my denial of being different from everyone else. When I tell people about my disease, I see that natural human reaction of concern wash over their face, and I promptly reject it. I run away from even the slightest indication that someone might feel sorry for me because I don’t feel sorry for myself.

Additionally, I also fantasize about old age, not as a possibility, but as an eventuality. I envision myself living a long life the way anyone else would. I’ve convinced myself of my own longevity and mentally rejected the very real possibility that death in general is instant and can target anyone.

While I know death is the only eventuality, and that mine could be much sooner than that of others, I’ve been clinging onto anything that reinforces the idea that I’m the same as a healthy person. My rejection of this disease being detrimental to my life has instilled in me a misguided feeling of complacency– as though things are guaranteed. Life and death are heavy on my mind but instead of using this to live a life worth leading no matter how short, I’ve chosen to still try and convince myself that I have time on my side.