Utilizing a craft that dates back thousands of years, young blacksmith Sven Undheim forges amazing, beautiful and strange art. As he goes through the process of fire welding a sword, he reflects upon his role as an artist versus blacksmith, and the dangers of working in the forge.

Photography by Sarah Romsaas Uggen

[hr style=”line” size=”1px”]

At Grünerløkka, next to Akerselva River, is Oslo National Academy of the Arts, locally known as KhiO. It is a school consisting of six departments, ranging from opera, to design, to fine art. The building has a very Hogwarts-esque feel about it. Wherever you go, you will encounter a different project in the works. Round one corner and find an abstract 3D cardboard sculpture, round another and see a massive painting of a foreign galaxy, or maybe a troupe of young dancers, working on a routine. It’s very easy to get lost in the faculty buildings, connected by underground hallways. In the basement of a secondary building is the school forge, where Master student Sven Undheim does most of his work.

He is a hard-looking man, sturdily built and covered in soot, small burns and scars, presumably from his work in the forge. Shaking his hand leaves a dark smudge of ash. Today, he’s working on a shortsword. “Swords and such is not that representative of what I do here,” he says. “My main project right now is a mechanical music box, but I’m waiting for materials to arrive before I can continue working on that. Meanwhile, I like keeping busy.”

He grabs part of an old train rail and exits the forge, heading over to a metal saw in the outside workshop to chop off a sizable chunk of it. The rail, along with some construction steel and forged down ball bearings will eventually become the body of the sword. The metal saw, like most of the machines in the forge and nearby workshop, looks very dangerous. Green, poison-like coolant drips from the blade as it slowly but surely slices through the cold steel.

[columns] [span4]

[/span4][/columns]

“We actually haven’t had that many injuries down here,” Sven says. “There was this one girl who forgot to put her hair up and got tangled into a lathe, which, thankfully, just ended in her losing a little hair and skin. They don’t look it, but they’re the most dangerous devices we have. They are incredibly powerful. If your clothes get sucked in, there’s nothing you can do. It will drag you in and rip you to shreds. Googling “lathe accidents” is awful (it’s true, don’t), people are just standing there with an arm ripped off of the socket, ceaselessly spinning around in the machine.”

The saw completes its course through the train rail, so he heads back to the now heated up forge to position the severed part into the tiny inferno, using big tongs. A hundred small sparks ascend into the huge ventilation shaft above as the metal hits the center of the fire.

“I haven’t had any injuries myself,” he continues, clearly ignoring the fact that his hands are covered in scars and first- to second-degree burns. He pauses and reconsiders. “Well, technically, I guess I’ve had a few scratches and burns here and there, but I think of injuries as some sort of permanent damage. Honestly, working here is quite safe, none of the machines are dangerous unless you’re a complete idiot. The most common danger in this line of work is inhalation of smoke and particles of dust and coal which may result in, well, cancer, or other permanent lung issues.”

He slowly and evenly heats up the clump of metal, repositioning it every now and then with a self-made fire poker. After a while, seemingly content with the feel and look of the it, he extracts it with the tongs and carries it to the corner of the room, where an especially menacing-looking machine awaits. The huge machine, known as a pneumatic hammer, seems made towards one single purpose: Smashing stuff. After placing the red hot metal on the anvil-piece of the machine, Sven pushes a green button and the monster comes to life, the hammer head rapidly pumping up and down, sounding like a steam locomotive at full speed. Sven gets a firm hold on the metal piece with the tongs and carefully positions it on the anvil of the machine before stepping down on a vertical metal bar, causing the hammer to come crashing down on the metal. Flames lick the surface of the molten steel as the machine batters it furiously, gradually flattening it. Then, in an instant, probably from the angle being slightly off, the glowing metal bar gets ripped out of Sven’s grip with the tongs, and clanks down on the stone floor next to the pneumatic hammer, inches from his feet. Thick black smoke starts rolling up immediately. With what seems like undeservedly little worry, Sven carefully picks it back up with the tongs and places it back on the anvil, before the fire can escalate further. Then he gets back to hammering it with the machine without a word, as if nothing had happened. When the once-rail has been sufficiently beaten into a long square rod, Sven dumps it into a nearby steel washstand, causing a satisfying fizz and a cloud of steam as it hits the chill water. Hitting the red button sitting under the green one, the violent machine finally dies down, at least for now.

[columns] [span6]

[/span6][span6]

[/span6][/columns]

“Most of what I do is self taught,” Sven says, with an absent look at the steaming washstand, where the metal is cooling down. “This is a school of art after all, not a blacksmithing school. They’ve facilitated it so that every individual student decide their course and focus on their own. I’m probably the student most focused on blacksmithing in the metalwork department, at least in recent years. Other people do other things. Some do casting, my girlfriend upstairs does jewelry, the guy with the desk neighboring mine mostly does digital work. You can pretty much do what you want, the common denominator is that we work with metal in some way.”

Whether I call myself an artist or a blacksmith doesn’t really matter to me. My ambition is being able to live off of doing, well, this, whatever you want to define it as.”

He pauses to check on the steel, quickly deciding it needs to cool further. “I identify more as an artist than a blacksmith,” he continues, “not because I consider that to be greater or cooler or anything like that, but I am working towards a Master of Fine Arts after all, and most of what I make is art. It’s better to be honest about what you are. Plus, blacksmith is a protected title in Norway, so I wouldn’t feel comfortable going around claiming to be one without completing an apprenticeship. Besides, whether I call myself an artist or a blacksmith doesn’t really matter to me. My ambition is being able to live off of doing, well, this, whatever you want to define it as.”

Now content with the temperature of the bar, he extracts it from the washstand and marks measurements with a piece of chalk before cutting it up into desirable pieces. “The technique is known as forge welding,” Sven states. “You stack steel parts on top of each other like a sandwich, (he holds up five pieces of flattened steel, including what used to be the train rail, to demonstrate) then you heat the metal up to 1100-1200° celsius (2000-2200ºF), apply borax (a red powder resembling rat poison) and hammer away on the anvil until the metal binds together into one piece. You stretch that piece out, cut it in two and stack those two pieces on top of each other again. Then rinse and repeat. This way you go from five layers, to ten layers, to twenty, forty, eighty, et cetera. You know those people on 4chan who talk about how katanas are so great because they’ve been folded a thousand times? This is what they’re talking about. Personally, I think fewer layers result in a better look. In the instance of this sword I’ll probably end up folding the steel somewhere between a hundred and two hundred times.”

Having placed the steel stack in the forge, causing a new burst of tiny sparks, a small column of smoke can suddenly be seen, rising from an ember on Sven’s waist. He has literally caught fire. Noticing it himself, he gently taps it, causing it to fizzle out. “That happens,” he says, indicating the rest of his t-shirt, covered in hundreds of scorched holes. “I use old shirts like these until they practically rot off of my body.”

The previously mentioned girlfriend and neighbor student show up to greet Sven. Upon being asked whether they consider him a blacksmith, they nod in unison. “He is a blacksmith,” Freja the girlfriend says with certainty, “even the teachers call this Sven’s forge. They will say stuff like “I think it’s in Sven’s forge”. Recently there’s been this other guy who’s been using the forge a little, and he will be like “no, it’s not just Sven’s…”, but it kind of is.”

Meanwhile, Sven has applied borax to the steel stack, and is now hammering it together by hand with practiced, fluid motions, creating a beautiful shower of sparks for every impact of the hammer. “The school likes showing me off during exhibitions and tours,” he says. “It looks old-fashioned and dramatic, and I mean, a gnome in the dark, pummeling stuff… That’s good entertainment for everyone. I do think it’s a little silly, though,” he adds, a little more seriously, “I think they put too much focus on this spectacle down here. Any one student is not representative.”

With the steel stack now merged and resting in the washstand, Sven succumbs to the pressing need for caffeine and heads toward his personal work station. While he claims it’s cleaner now than it has been for six months, it’s completely littered with various materials, tools, trinkets, projects and apparent junk.

With the steel stack now merged and resting in the washstand, Sven succumbs to the pressing need for caffeine and heads toward his personal work station. While he claims it’s cleaner now than it has been for six months, it’s completely littered with various materials, tools, trinkets, projects and apparent junk.

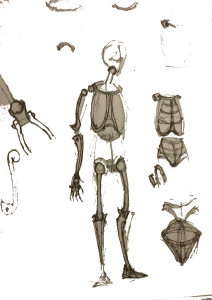

Being asked to showcase some of his work, he grabs a grim headless statue and holds it up like a prize-winning trout. “I’ve become quite fascinated with mechanics and making realistic joints. This project is a practice in making movable parts. All the joints, especially the ball joints, is something I’m very proud of. The balls are forged, sharpened and polished by hand, and everything has been bonded through traditional means and techniques. It’s being held together by rivets and clamps. In theory, you could take it apart and put it back together, although that would involve a lot of work. I decided to make this as ornamented and full of flourishes and spirals as possible, because that’s something you’re not really supposed to do in artistic forging – it’s considered extremely kitsch. I suppose it’s something I had to get out of my system.”

Before deciding to make a music box, Sven made a metal arm, attached to a pole, that rotates by pumping on a pedal at the foot of the contraption. “I’m very happy with this,” he says, “it’s one of my first mechanical projects. Not that the mechanics are that advanced, but it works.”

“There isn’t really that much artistic symbolism behind it,” he adds, upon being asked. “I enjoy creating slightly absurd art that interacts with the audience in some way and is fun. Art that doesn’t take itself too seriously.”

Another slightly absurd, interactive creation of Sven’s is an ominous-looking massive set of jaws, sitting in the corner of the room. By winding it up, it generates power that can be released in an explosive burst of energy to rapidly clack its metal teeth together. “The thing holding the cogwheels together is torn from use, so it doesn’t clack the way it should,” Says Sven, pointing to the insides of the jaws. “Also, it doesn’t have any sensible gearing, so it runs out of steam in a second, which wasn’t my intention. I learn a lot through experimentation, though,” he adds. “By creating the jaws and rotating arm, I have hopefully gained the knowledge and experience needed for my mechanical music box to work out as planned.”

Most of Sven’s projects are done for the sake of learning. The first year of a Master’s education at his department of KhiO is considered a try-out year where students attempt to figure out in which direction they want to go for their final project. “I’m thinking about getting into steam power for my next semester,” Sven says. “Create simple steam machines that power my constructions instead of using springs, which is what I’m currently doing. Further technology beyond that, though… I like keeping things a little primitive and not being dependent on electricity for my machines, because then they wouldn’t be as autonomous. Take the wind-up jaws for example, they’ll work wherever you take them – all they require is human power. I find that very appealing.”

Back in the forge, the steel bar that will eventually become a sword has cooled to a temperature that will not turn your skin to crisp. After cutting it in two, Sven holds up one of the pieces, exposing the inner surface of the bar, and the result of todays work. “No air or gas particles, no cracks, no slag,” he concludes, happily.

Now remains five-six rounds of folding the metal. Then comes the actual shaping of the sword followed by tedious grinding and polishing. Lastly is the making of a shaft and scabbard. All in all, the process will likely take several days. Should he make any mistakes, everything could come undone, forcing the young blacksmith to start all over again.

“Naturally, I’m a little worried in regards to my future,” Sven says, staring into the fire of his forge. “There isn’t much demand for a blacksmith in our day and age. I don’t expect to leave this school being able to live off of doing this full-time, I’ll have to test the waters and see if there’s hope for me… On the other hand, not many people can do what I can.”